Castrapolis: Neapolitan Cantatas and Arias

Johann Adolph Hasse (1699-1783)

‘Non piangere, amati rai’, from Ciro reconosciuto (1751)

Giuseppe Porsile (1680-1750)

Six Arias, from Il ritorno di Ulisse alla patria (1707)

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725)

Quella pace gradita.

Domenico Auletta (1723-1753)

Concerto (in C major) for harpsichord, two violins and basso continuo

Domenico Natale Sarro (1679-1744)

Dimmi bel neo che fai

Traditional

Tarantella de Gargano, voice and baroque guitar.

Nicolò Balducci (countertenor)

Anna Paradiso (harpsichord), Dohyo Sol (baroque guitar)

Dolci Affetti/Dan Laurin

rec. 2021, Duvbo kyrka, Sundyberg (Sweden)

Texts and translations provided.

BIS BIS2585 SACD [81]

The booklet note to this disc, by Dinko Fabris – author of, amongst other things, Music in Seventeenth-Century Naples: Francesco Provenzale:1624-1704, 2007and Partenope da Siren a Regina: Il mito musicale di Napoli 2017 – tells us that “the term ‘Castrapolis’ was used in Dominique Fernandez’s celebrated 1974 novel Porporino ou les mystères de Naples, to describe the southern capital [i.e. Naples] with its high concentration of castrato sopranos”. Fabris prefaces his notes with an epigraph from Storia irreverente di eroi, santi e tiranni di Napoli (2017) by Giovanni Liccardo:

“Naples has a special class of men. It is the home of castrati and layabouts. Those shameful operations that we judge indispensable for maintaining our theatres are practised only at Naples. And thus it is the dregs of the populace that sacrifice their youth in the hope of future advantage. Luigi Conforti, letter of a ‘Dutch professor’.”

I am not sure whether or not Dr. Fabris accepts the claim that the castration of boys between the age of 6 and 12 was an operation “practised only in Naples”? It seems unlikely to be true. In the Eighteenth Century that inveterate seeker out of ‘musical’ information Charles Burney made enquiries about where castrations took place: “I was told at Milan that it was at Venice; at Venice that it was at Bologna; but at Bologna the fact was denied, and I was referred to Florence; from Florence to Rome, and from Rome I was sent to Naples … it is said that there are shops in Naples with this inscription: ‘QUI SI CASTRANO RAGAZZI’ (“Boys are castrated here”); but I was utterly unable to see or hear of any such shops during my residence in that city.” (Dr. Burney’s Musical Tours in Europe, ed. P.A. Scholes, Oxford, 1959, Vol. 1, p.247). Nor did the Neapolitans did make any admission that their city was the ‘home’ of this practice. Professor Helen Berry – in her fascinating book (The Castrato and His Wife, O.U.P., 2011) about the ‘scandalous’ marriage between the Italian castrato Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci and one of his singing pupils, Dorothea Maunsell – considers such matters, while showing that the young Tenducci was castrated in the Tuscan hill town of Monte San Savino in 1748, by one Pietro Massi, a travelling barber-surgeon. There probably was no one place in Italy where the “shameful operations” took place”. What was true and of more directly musical importance, was that the four musical conservatories of Naples, the Conservatorio di Santa Maria di Loreto, the Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio a Capuana, the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo and the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini were more involved in the musical training of young castrati than any other organisations on the Italian peninsula. Most of the castrati who became stars in the opera houses of Europe, not least those in Naples, were ‘graduates’ of one or other of the Neapolitan conservatories.

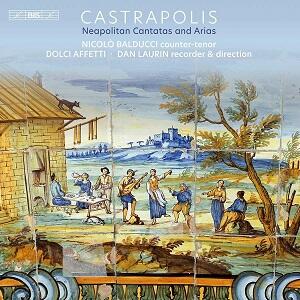

So, obviously, there are senses in which Naples could be seen as the city of castrati, even if it wasn’t the only place where boys were operated on so as to become singers. It is also the case that most of the music on this album is closely connected with Naples. The title of this disc is fitting, therefore, as is the fact that the box and booklet of this disc are graced by photographs of some of the beautiful majolica tiles with which the cloister of the former Neapolitan convent of Santa Chiara is decorated.

All of the named composers have significant connections with the city. Perhaps the least-known of them, Domenico Auletta, was born in Naples and died there aged only 30. He was an organist and the son of Piero Auletta (1698-1771), also a composer – of, for example, the opera Orazio (1757), sometimes wrongly attributed to Pergolesi – and also relatively little known. Domenico studied at the Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio; his output includes a number of Psalm settings – including a Dixit Dominus – and a Requiem Mass, as well as three concertos for harpsichord, violin and continuo, all three preserved in a manuscript now in the library of the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella in Naples. He had a son, who was also given the name Domenico and was also a composer; these three concertos have sometimes (e.g in Donald E. Freeman’s ‘The Earliest Italian Keyboard Concertos’, The Journal of Musicology, 4(2), 1985/6), 121-45) been attributed to the younger Domenico Auletta.

Though born in Palermo, Alessandro Scarlatti, father of Domenico, was most closely associated (in musical terms) with Naples. His early studies were in Rome, where he wrote his first, very successful opera (Gli Equivoci nel sembiante) at the age of 18. In 1683/4 he was appointed maestro di cappela to the Marquis del Carpo – viceroy of Naples. For around twenty years he was the dominant figure in Neapolitan opera, writing more than 40 works for the stage. He left Naples in 1702, going to first to Florence and then to Rome where he became maestro di cappella at Santa Maria Maggiore. His attention now turned more to sacred music rather than opera, the Roman theatres having been closed by papal decree in 1700. In 1709 he returned to Naples, continuing to compose prolifically and to teach. One of his pupils, from 1722, was Joseph Adolph Hasse.

Hasse’s father belonged to a long line of organist-composers in Hamburg, but his son displayed an early fascination with opera and chose to study singing, before joining (as a tenor) the city’s opera company in 1718. He moved on to the court of Wolfenbüttel, where his first opera (Antioco) was performed in 1721, with the composer in the title role. In the following years he travelled to Italy and began studies with two Neapolitan masters, first with Nicola Porpora and then with Alessandro Scarlatti. He went on to write many operas for theatres in Italy and Germany. In 1730 he married the famous soprano Faustina Bordoni and in 1731 was made Kapellmeister at the court of Dresden. The rest of Hasse’s hugely successful career need not concern us here, save perhaps to note that a number of his later operas were premiered in Naples (sometimes as revisions of works premiered elsewhere in an earlier version), e.g. Issipile (1732), Demofonte (1758), La clemenza di Tito (1759) and Artaserse (1760).e HeIn

While Hasse bestrode the world of European music, Giuseppe Porsile was a figure of far less importance, even if his talents obtained him significant positions beyond Naples, where he was born. His father Carlo composed at least one opera (Nerone, 1686) and was presumably his son’s first teacher. Giuseppe had his more formal musical education at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo. In his twenties, as assistant maestro di cappella at the Spanish Chapel in Naples, some of his music attracted so much favourable attention that he was given the opportunity to work at the court of Charles II and III in Barcelona, where he remained until 1713; in the following year he was given a position at the imperial court in Vienna, initially as singing teacher to the Empress, though in 1720 he was made Court Composer. He died in Vienna in 1750. During his years in Vienna, he seems to have written over 20 works for the stage and around 13 oratorios.

So far as I can see, Domenico Natale Sarro’s musical career rarely took him beyond Naples. He was born at Trani on the Adriatic coast in Apulia, on December 24th 1679 – hence the second of his given names. He was trained in Naples at the Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio and in 1704 he was made vicemaestro di cappella at the court of Naples. In 1706 his oratorio Il fonte delle grazia was performed in the Chiesa dei Girolamini in Naples. His career as a composer of opera began in the following year, when Il Vespasiano was premiered at the city’s Teatro San Bartolomeo. He wrote around 20 further operas, almost all of which were premiered in Naples; one exception was La caduta de decemviri of 1623, which was premiered at the Regio Teatro Ducale in Milan. Hto be made is reputation clearly spread beyond Naples, since he was one of the handful of composers, as opposed to poets and men of letters (others so honoured included Alessandro Scarlatti, Corelli and Pasquini) to be made a member of Rome’s prestigious Accademia dell’ Arca, which is often referred to as Accademia dell’Arcadia (see Malcolm Boyd, ‘Rome: The Power of Patronage’, in Music and Society: The Late Baroque Era, ed. George J. Buelow, Basingstolke, Macmillan Press, 1993, p.48).

We have, then, an interesting programme of music by composers who, in various ways, could all be said to belong to the Neapolitan school. There is nothing here by the city’s major composers (save for Alessandro Scarlatti) such as Francesco Durante, Niccolo Piccinni, Leonardo Leo, Francesco Provenzale, Pergolesi, or Leonardo Vinci; still, recordings of many of their works are already widely available, and all of the music heard here is, at the very least, interesting and some of it is more than merely interesting.

Anyone who has heard much of Hasse’s music will not be at all surprised to hear that the music which opens the disc, an aria from his opera Ciro riconosciuto, belongs in the “more than merely interesting” category; so, too, does Scarlatti’s cantata Quella pace gradita. The works by Porsile and Sarro came as pleasant surprises – given how relatively little-known both composers are. The concerto by Auletta is perhaps the one work for which the adjective ‘interesting’ might be sufficient – some might say generous – despite the excellence of the soloist (harpsichordist Anna Paradiso) and her accompanists.

In all the vocal works the soloist is the remarkable countertenor/sopranist Niccolò Balducci. Leaving aside unanswerable questions about how far a modern countertenor could ever reproduce the ‘sound’ of the castrati, there is no doubting the fact that Balducci has a good deal, at least, of that virtuosity for which the best of the castrati were admired in their time, when they dazzled audiences with “their command of vocal agility – of trills, runs and ornamentation” (John Rosselli, entry on ‘Castrato’ in The Grove Dictionary of Opera, 1992, Vol.1. p.766). Balducci’s singing, full of energy and speed, is certainly agile and communicates both a joy in the act of singing and a pleasure in what is own voice can do, that doesn’t always sit altogether comfortably with the text he is singing. So, for example, in Cambise’s aria ‘Non Piangete, amati rai’ from Act I of Ciro riconosciuto some of the bending of notes and the vocal swoops up and down don’t seem apt to the words of consolation which Cambises, who is under sentence of death, is addressing to his wife Mandane. Elsewhere, Balducci’s vocal acrobatics are heard to greater effect, since they are more appropriate, as in ‘Sventurato chi piagato’ from Porsile’s Il ritorno di Ulisse alla patria, in which the singer tells of the wretchedness of the lover ‘wounded by Cupid’ in music which, like so many operatic expressions of this sentiment, blurs the distinction between suffering and celebration in passages of impassioned coloratura.

My own reaction to Balducci is, on the whole, more positive than negative. He can sing with appropriate restraint when this is required – a beautiful example can be found in the third of the arias from Porsile’s Il ritorno di Ulisse alla patria, ‘Apri Cirene il lumi’, a moving piece in which, supported by the delicacy of Dan Laurin’s recorder and Anna Paradiso’s harpsichord, Balducci gives beautiful expression to Porsile’s subtle setting of the sensitive words of librettist Giovanni Andrea Moniglia – who doesn’t seem to be mentioned anywhere in the documentation with this disc. This is unfortunate since this and some other libretti by him (such as those for Cesti’s La Semirami and Legrenzi’s Ifianessa e Melampe) suggest that the Florentine-born Moniglia was one of the finest librettists of his day.

As implied earlier, the harpsichord concerto by Auletta is pleasant, without being especially distinctive or memorable. The two outer movements, both marked Allegro, are showily inventive; the central movement (Larghetto) lyrical in a characteristically Neapolitan manner.

Domenico Sarro’s secular cantata Dimmi bel neo che fai sets a typically fanciful baroque poem, in which a mole near the beloved lady’s lips is, by turns, a “nunzio … de morte” [a warning of death] and a “calamita fatal de’ cori amant” [the inevitable magnet of loving hearts]. Sarro’s setting – and Balducci’s voice – capture very effectively the union of the solemn and the absurd in a text like this, particularly in the second aria of the cantata:

Che vaneggia quest’alma smarrita

con un neo che senso non ha.

Se il mio bene che darmi può vita

di mie pene ben sente pietà.

Throughout the disc the work of Dolce Affetti is impeccably idiomatic and supportive. Dolce Affetti is, I believe, an ensemble put together specially for this project and, so far as I can see, it is made up of Swedish musicians and/or musicians based in Sweden, all of them specialists in the baroque. Its co-directors are the Swede Dan Laurin and the Italian Anna Paradiso (who happen to be husband and wife). An unsigned note in the programme tells us that the ensemble “wishes to celebrate the cultural pluralism of Europe which once again is under threat from commercial interests and/or international politics”; the aim is a laudable one and through their programme and performances they are persuasive advocates for it.

It is Anna Paradiso who provides a note on the final item on the disc the ‘Tarantella di Gargano’. She begins her note by pointing out that this tarantella “comes from Apulia, the region of Domenico Sarro and the castrato Farinelli (as well as of Nicolò Balducci and Anna Paradiso” – neatly tying together several aspects of the disc. She adds that “[t]his particular tarantella is of the slow type, and comes from Gargano, a mountainous peninsula on the Adriatic coast. It was used by street musicians as a serenade”. She concludes her note thus: “For a singer who is not from Southern Italy it is almost impossible to pronounce the text in a convincing way. On the present recording, Balducci uses an accent close to his own mother tongue, which is a Southern Italian dialect similar to the one from Gargano.”

Balducci certainly sounds thoroughly at home in this final piece – here he is very much a singer articulating his place in a way that almost instinctively embodies that place’s tradition and its ways of thought. Coincidentally, not long before I received this disc I had been relistening to a recording by Christina Pluhar and her ensemble L’Arpeggiata, La Tarantella -Antidotum Tarantulae (Alpha 503) which contains a version of the ‘Tarantella di Gargano’ in which Marco Beasley is the singer. Although I am an admirer of both Pluhar and Beasley, I have to say that Balducci’s account of this Tarantella makes that by Pluhar and Beasley sound too ‘studied’, well-schooled rather than instinctive. With Balducci, accompanied by the baroque guitar of Dohyo Sol, we are nearer to the streets of Southern Italy – I could almost taste the bombette (one of Apulia’s most popular kinds of street food, fritters made of pork neck stuffed with cheese and seasoning).

Glyn Pursglove

Help us financially by purchasing from