Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968)

52 Greeting Cards, Op. 170: 21 pieces for guitar

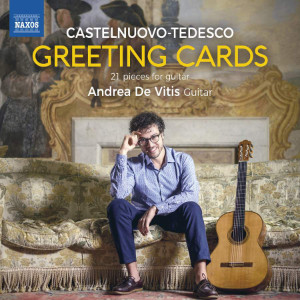

Andrea De Vitis (guitar)

rec. 2022, St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Newmarket, Canada.

NAXOS 8.574246 [72]

Between 1953 and 1968, the self-exiled Italian composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, who lived in the USA from 1939 (he was Jewish) wrote 52 short pieces to which he gave the general title Greeting Cards. These were dedicated to fellow composers, instrumentalists, friends and students – the people one might describe as the inhabitants of his musical world. In writing these pieces Castelnuovo-Tedesco used a personal form of musical cryptography. As Frédéric Zigante writes – as translated by Gail McDowell – in his booklet essay “the cryptography that Castelnuovo-Tedesco used in his Greeting Cards was regulated by a combination of letters/notes that he personally established a priori”. He generally used this ‘code’ to generate two themes – one ascending, one descending from the name of the dedicatee and then “continued free of any further restrictions” (Zigante). (Zigante, incidentally, edited the first critical edition of these 21 pieces, published by Ricordi in 2019).

It is important to understand that the Greeting Cards were not conceived of us a structured sequence or cycle. The set does not, that is, work through from a beginning to a conclusion. Each piece was written as and when Castelnuovo-Tedesco found occasion for it. The last pieces in the collection were written in the year of the composer’s death and there is no reason, so far as I know, for believing that he would not have written more had he lived longer.

Amongst the 52 pieces which make up Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s set of Greeting Cards, there are 21 written for solo guitar, 18 for solo piano (such as No.1 ‘Tango on the name of André Previn’ (1953) and No.16 ‘Ricercare sul nome di Luigi Dallapicola’ (1968); there is one piece for two pianos, No. 19 ‘Duo Pianism: Impromptu on the names of Hans and Rosaleen Moldehaur’ (1959), dedicated to a couple who assembled one of the great collections of music manuscripts, now housed in the Houghton Library at Harvard University. No.45 is an arabesque for harp on the name of Pearl Chertok’, while No. 2 is a ‘Hungarian serenade on the name of Miklós Rósza’ and No. 3 is for solo cello, being a ‘Valse on the name of Gregor Piatigorsky’ (for whom Castelnuovio wrote a cello concerto).

On this disc Andrea De Vitis plays all 21 of the pieces for guitar which are included in Greeting Cards. All the pieces are brief, the longest (No. 5) being, in this recording, just over 5 minutes long, and the shortest (No. 42) just under two minutes. Some may assume that pieces as short as this must, necessarily, be somewhat insubstantial, but I take a different view. Brevity, in a temporal medium like music or smallness in a ‘spatial’ medium like the visual arts need not, of itself, be symptomatic of triviality or lack of ‘substance’. Indeed, ‘small’ works of art are, of necessity, concentrated, which produces a distinctive kind of intensity of beauty and power. If one thinks, for example, where poetry is concerned, of the finest examples in a form such the seventeen-syllable Japanese haiku, such as this by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), in an English version by Michael R. Burch:

See: whose surviving sons

visit the ancestral graves

white-bearded, with trembling cranes?

or of a great epigram such as this by Alexander Pope

Nature, and Nature’s laws lay hid in night.

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.

Poems such as these have resonances of emotion and meaning out of all proportion to their ‘size’. The same is true in the visual arts. The traditions of Miniature painting, whether Persian, Mughal, Byzantine, Turkish or Armenian produced many works which, while tiny in size, ‘pack a forceful’ punch. Nicholas Hilliard’s tiny portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh – 1.8 inches high and 1.4 inches wide, now in the collection of London’s National Portrait Gallery, contains as much, or more, sense of character as most much larger portraits. The same might be said of some of the portrait medals so popular during the Renaissance. Here the fact that the medal was two-sided added to what could be ‘said’ about the subject. One striking example, in the British Museum is the medal of Giovanna Albizzi Tornabuoni (with a diameter of only 76mm.) probably created by Niccolò Fiorentino; the obverse has portrait in profile in which the sitter is described as “Uxor Laurentii de Tornabonis Ioanna Albiza” (The Wife of Lorenzo Tornabuoni, Giovanni Albizza”: the reverse carries a lovely image of the Three Graces, with the legend “Castitas Pulchritudo Amor” (Chastity, Beauty, Love), obviously intended as prize of the lady. This medal is illustrated and discussed in The Currency of Fame: Portrait Medals of the Renaissance, ed. Stephen K. Scher, 1994).

In terms of music, one might think, to take a few examples, of Schubert’s Allegretto in C minor, D 915, a performance of which lasts around the five-minute mark or of some of the most interesting pieces in Robert Schumann’s Bunte Blätter, Op.99, such as ‘Praeludium’ (generally around 1 minute twenty seconds in performance), ‘Abenmusik’ (c. 3.30-3:40) and ‘Geschwindmarsch’ (c. 3:00-3:20). Surely it could only be the rash or the insensitive who would dismiss these compositions as trivial because of their brevity. Or, to take a final example, from the world of jazz, the piano of Earl Hines and the trumpet of Louis Armstrong created in 1928, in a piece called ‘Weather Bird’, a work of remarkable virtuosity and invention, though it lasts less than three minutes.

So, there is no inherent reason for regarding Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Greeting Cards as slight works. In all of them I hear both the composer’s musical and cultural sophistication and the warmth of friendship and/or admiration. Graham Wade summed up Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s contribution to the development of the guitar’s repertoire when he wrote (in words that might almost serve as a description of the music on this disc) that he “liberated [the guitar] from its role as a vibrant mirror of folk vitality” enabling it to “assume another identity as the creator of intimate worlds of sensibility, imagination, romance, and sometimes the realm of the sentimental” (Traditions of The Classical Guitar, London, 1980, p.176).

Of these 21 Greeting Cards written for solo guitar the majority are addressed to people best known as guitarists or guitarist-composers. These range from a legendary figure of the instrument like Andrés Segovia, through the internationally well-known such as Siegfried Behrend and Laurindo Almeida to those who are likely to be known to students of the guitar or those with a particular interest in the instrument and its repertoire but not widely known beyond such circles, such as Ruggero Chiesa (1933-1993), an Italian guitarist, editor and teacher or Manuel López Ramos (1929-2006), a fine, but oddly under-appreciated guitarist (most of his recordings don’t seem to have been transferred to CD), as well as respected teacher and a composer for the instrument. These, and others, all get appropriate Greeting Cards from Castelnuovo-Tedesco. Fittingly the first Greeting Card written for guitar was No. 2 ‘Tonadilla on the Name of Andrés Segovia’. Castelnuovo-Tedesco was not a guitarist – his instrument was the piano, which he called his “favourite instrument” and his “confidant”. His love of the guitar and his desire to write for it was stimulated by early experiences of hearing Segovia, with whom he entered a correspondence which lasted some 36 years. There is an illuminating doctoral thesis by Benjamin Bruant (University of Surrey, 2020), From Commission to Publication: A Study of Mario Castelnuovo’s Guitar Repertoire Informed by his Correspondence with Andrés Segovia, which throws much light on the nature and importance of this relationship; it is available for consultation here. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s output for guitar included works such as (this is a small selection) Le Capriccio diabolico, Op.85 (1939), Guitar Concerto No. 1, Op.99 (1939), Suite pour guitare seule, Op.133 (1947), Guitar Quintet, Op.143 (1950) for guitar and string quartet, Guitar Concerto No.2, Op.160 (1953), 24 Capriccios de Goya, Op.195 (1961), Les Guitares ben tempérées: 24 preludes and fugues for 2 guitars, Op.199 (1962) and Concerto for Two Guitars, Op.201 (1962). His ‘discovery’ of the guitar, under the influence of Segovia (who he first met in 1931), seems to have enabled Castelnuovo-Tedesco to make use of an important part of his cultural heritage – that which he inherited from his distant ancestors, who were Sephardic Jews forced out of Spain, which they left for Italy, at the end of the fifteenth century. Fittingly, it is his ‘Tonadilla on the Name of Andrés Segovia’ which opens this recording of the Greeting Cards for solo guitar – and what a striking piece it is, with its spacious treatment of a kind of melancholy, free of self pity, that is distinctively Spanish, and its perceptive comprehension of essentially Spanish idioms. Andrea De Vitis plays it with great certainty of technique and his phrasing and judgement of tempo are excellent; he seems perfectly attuned to the sensibility underlying the music.

Indeed, De Vitis’s work throughout the disc is assured and perceptive. He negotiates, without any audible problems, the varied rhythms and idioms of these pieces – whether that be the subtle charm of the charming lullaby, ‘Ninna Nanna’ written for one of his students, Eugene Robin Escovado, of whom I know little, save that he was born in San Diego and was a pianist or, on the other hand, the Latin American flavours of the ‘Cancion venezolana’ written for the guitarist – and composer – Alirio Diaz, who studied with Segovia and was the dedicatee of Joaquín Rodrigo’s Invocacíon y danza: Homenaje a Manuel De Falla (1961). I have been especially fascinated by the ‘orientalism’ of such Greeting Cards asNo.10 ‘Tanka (Japanese Song) on the name of Isao Takahashi’ and No.46 ‘Japanese Print on the Name of Jiro Matsuda’.

Based on his more ‘public’ compositions, Castelnuovio-Tedesco has always struck me as a composer who wrote out of a rich and varied cultural life; this is neatly illustrated by, to take just one area of his work, his songs. The poets set by him range, almost dizzyingly, from Rabindranath Tagore to Sir Walter Scott, from Paul Verlaine to Moses Ibn Ezra, from Dante to Heinrich Heine and from Robert Burns to Petrarch! His music also responds to the visual arts, as in the 24 Caprichos de Goya, for solo guitar (1961) or his Tre fioretti di Santo Francesco which articulates musical responses to Giotto’s images of Saint Francis. Yet alongside all his cultural allusiveness I have often felt in the music of Castelnuovo-Tedesco what I can only describe as a desire to celebrate the gifts of friendship. I was therefore pleased recently, to come across the following tribute to the composer, from one who knew him well:

“Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco was not only the kindest and most generous man I have ever known, he was also the most brilliant. Easily conversant in more than a half dozen languages, he was intimately acquainted with all the major works of literature in their original languages: Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French, English, German, and Hebrew. He knew well the masterpieces of western art – sculpture, oils, frescos, mosaics and drawings – and could describe in detail the galleries, churches, and museums in which they could be found. And, of course, his knowledge of music was profound” (Nick Rossi, ‘Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Modern Master of Melody’, in American Music Teacher, 25:4, 1976, pp. 13-14, 16. Quotation from page 13).

The richness of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s familiarity with large areas of western culture is evident in much of his music, these intimate pieces being no exception. It is part of what gives these short pieces their aesthetic gravity.

On pretty well every occasion that I have listened to Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s music I have been, in the most positive sense of the word, ‘instructed’, have learned something about the interconnections out of which our imaginative world is made. His own music suggests why he became such an influential teacher during his years in California, where his students included André Previn, Marty Paich – a significant jazz pianist and arranger; in this context it is worth noting that the subject of the last guitar piece in the Greeting Cards, No. 50 ‘Tarantella campana on the name of Eugene di Novi (1967)’ is a fine jazz pianist generally known as Gene DiNovi, who was an active figure in New York jazz in the 1940s and early 1950s, working with Lester Young and many others; he went on to work as an accompanist with several jazz and jazz-influenced singers, including Anita O’Day, Tony Bennett, Peggy Lee and Carmen McRae, before moving to California, working as an arranger and composer in Hollywood. Evidently, he and Castelnuovo-Tedesco must have met there. A number of better-known composers of film music studied with Castelnuovo-Tedesco, including Jerry Goldsmith, Nelson Riddle, Henry Mancini and John Williams.

The obvious comparison, where this disc is concerned, is with the recording of these same pieces by Cristiano Porqueddu, spread across two CDs (Brilliant Classics 96051). There isn’t, in truth, a great deal to choose between the two recordings; where individual pieces are concerned there are sometimes reasons to prefer one to the other, but these don’t, for me, add up to a judgement that one recording is ‘better’ than the other. Porqueddu sometimes deploys a slightly broader palette of instrumental colours, but I find De Vitis superior as regards rhythmic control and judgement of tempo. If forced into making a recommendation I would opt for De Vitis, but both guitarists serve Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s music well and either would make a sound investment. The more I listen to these ‘miniatures’, the more I feel that the composer was being excessively modest when, in his autobiography, Una vita di musica: un libro di ricordi, ed. J. Westby (Fiesole, 2005), he described them as “modest little pieces”.

Glyn Pursglove

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

No.5 Tonadilla on the name of Andrés Segovia (1954)

No.6 Rondel on the name of Siegfried Behrend (1954)

No.7 Preludio in forma di habanera on the name of Bruno Tonazzi (1954)

No.10 Tanka (Japanese Song) on the name of Isao Takahashi (1955)

No.14 Ninna Nanna, a Lullaby for Eugene, (1957)

No. 15 Song of the Azores in the name of Enos (Joseph Enos) (1958)

No. 33 Canzone Siciliana on the name of Gangi (Mario Gangi) (1962)

No. 34 Ballatella on the name of Christopher Parkening, (1963)

No.36 Sarabande on the name ofRey de la Torre (1964)

No.37 Romanza sul nome di Oscar Ghiglia (1964)

No. 38 Homage to Purcell, Fantasia on the names of Ronald and Henry Purcell (1966)

No.39 Canción cubana on the name of Hector Garcia(1965)

No. 40 Canción venezuelana on the name of Alirio Diaz (1966)

No. 41 Canción argentina on the name of Ernesto Bitetti (1966)

No. 42 Estudio sul nome di Manuel López Ramos (1966)

No. 43 Aria da chiesa sul nome di Ruggero Chiesa (1967)

No. 44 Brasileria sul nome di Laurindo Almeida (1967)

No. 46 Japanese Print on the Name of Jiro Matsuda (1967)

No. 47 Volo d’angeli sul nome di Angelo Gilardino (1967)

No. 48 Canzone Calabrese on the name of Ernest Calabria (1967)

No. 50 Tarantella campana on the name of Eugene di Novi (1967)