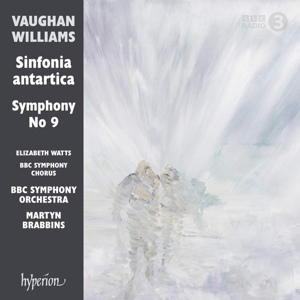

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Sinfonia antartica (Symphony No.7) (1949-1952)

Symphony No.9 in E minor (1956-1957)

Elizabeth Watts (soprano), BBC Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Martyn Brabbins

rec. 2022, Watford Colosseum, Watford, UK

Hyperion CDA68405 [79]

With this sixth disc in the series, Martyn Brabbins and the truly excellent BBC Symphony Orchestra complete their cycle of the nine Vaughan Williams symphonies for Hyperion. The project has spanned some four and a half years since A Sea Symphony was recorded in October 2017 and collectors who have been eagerly awaiting this final release will not require the prompt of any review to snap up a copy. The day I received this review copy I also heard that Hyperion itself is being sold to Universal Music. The hope must be that it will be able to retain its unique artists and repertoire roster but it might well be that this cycle and the substantial investment of time, effort and cost by all involved might well be one of its last independent productions.

I imagine the original plan was for the cycle to be completed by the 150th Anniversary of the composer’s death but the wait has only been a couple of months. Many of the qualities evident throughout this series continue with this disc. In terms of presentation, production and recordings these discs have been consistently high quality with producer Andrew Keener presiding over his fourth(!) cycle – I know the Handley and Slatkin cycles but not the Manze. For Hyperion the engineering has been overseen – with the exception of the previous release of Symphonies 6 & 8 – by Simon Eadon and I have to say this disc might just be the finest yet in terms of superb handling of instrumental textures, orchestral soundstage and sophisticated balances. On the podium Martyn Brabbins has been an assured and sensitive guide to these multi-faceted and emotionally wide-ranging works. As ever there have been highlights with the cycle as a whole and within individual works. My sense is that this final disc embodies many of the qualities that have been evident across the cycle as well as underlining an approach which is musically quite centrist. One of the features of the series which I have enjoyed has been the inclusion as ‘fillers’ rare, indeed unknown, works by Vaughan Williams. In this instance since the two symphonies alone run to 78:44 that has not been possible but this is clearly a generously filled disc.

The genesis of Sinfonia antartica as a film score for Scott of the Antarctic is well known and does not requiring repetition here. A legacy of the film score origins is the cinematic scoring, rich in instrumental colour and incident, of the symphony. This is where this new recording is wonderfully successful. I am not sure I have heard the orchestral detail of strumming harps, low piano, tuned percussion, lumbering organ pedals ever so effectively integrated yet audible. There are two technical aspects of this recording which impact on the performance that do need addressing. Vaughan Williams deploys a wordless soprano solo and female chorus at key moments as a strangely disembodied representation of the icy polar wind. The soloist here is Elizabeth Watts and to my ear she is excellent – a quite light voice but well-focussed. Likewise the BBC Symphony Chorus sing well – personally I feel they could have been recessed more into the orchestral soundscape – their function is as an instrumental colour/timbre and ideally the listener should not be aware where instruments end and voices begin. Woven into that same aural texture Vaughan Williams uses a wind machine and in the orchestral score it is carefully annotated with dynamics and expression marks for the player to observe. For some unfathomable reason the wind-machine (a fairly crude instrument to be sure) has been substituted in this recording with post-production overlaying of actual recording of wind. Perhaps because my ear has become so used to the presence of a wind-machine that I find the “real” wind to sound less effective. Also, the carefully placed dynamics can only be followed by cranking the level of the sound-effect up and down on the recording desk. The score is marked very exactly with the chorus, low strings, timpani and wind machine all fading into the distance together with the marking “niente” [to nothing]. Here we get a final 20 seconds or so of wind-sample “solo”. This is not a deal-breaker for me but a strange and unsatisfactory production decision giving the work a cinematic sound-effect ending that is not what the composer wrote. Curiously Keener did exactly the same thing with Slatkin but with a more distanced wind machine [I had never noticed this before checking that recording as part of this review] but followed the score exactly with Handley which to my ear is the better solution.

Throughout both symphonies Brabbins chooses effective and sensible tempi. Overall I think this Antartica is a successful version, not just helped by the clarity of engineering but also by the genuinely beautiful playing of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. If I had one observation – and I found much the same to be true of Mark Elder’s refined performance – the sheer power and elemental nature of the two or three great climaxes in the work lack the impact of some performances. This was where Haitink’s recording – which won the 1986 Gramophone ‘Orchestral’ award – was very effective. However, the overall arc of this performance is effective and convincing and to my ear more satisfying than Mark Elder’s well-played but slightly understated performance with the Hallé Orchestra which I reviewed here.

Vaugahn Williams’ final completed essay in symphonic form Symphony No.9 in E minor remains an elusive, probably unappreciated, yet genuinely remarkable work. Robert Matthew-Walker’s informative liner explains that sketches for a further two symphonies were found in the composer’s papers after his death but whether those sketches post-date the completed 9th or not is unclear. Even with the benefit of hindsight, a palpable sense of leave-taking and valediction imbues the work’s closing pages. But perhaps even more remarkable is the way the composer in his mid-80’s was avidly exploring timbres, textures and symphonic form. This work gives principals within the orchestra a greater chance to shine and in this new recording, again aided by the beautiful engineering, shine they most certainly do. Paul Mayes’ flugelhorn is simply ravishing throughout while near the beginning of the work there is a passage for the clarinets led by principal Richard Hosford of melting beauty. But these are just two examples of many with the BBC SO collectively and individually shining. By that measure of excellence, Brabbins’ interpretation is perhaps just a little plain and undercharacterised. The use of the three saxophones does not seem as gleefully subversive as it can, the angularity of the score is minimised and the pastoral beauty – of which there is much – is emphasised. As mentioned I have not heard Andrew Manze’s recorded cycle where the Symphony No.9 proved controversial through his use of slow tempi. However, I did hear Manze in concert with the LPO at the Festival Hall in London last Autumn in this work. Manze did not reproduce those slower tempi then but his performance was powerful and dramatic and one which emphasised the remarkable fertility of imagination of the octogenarian composer. The recent re-release of Malcolm Sargent’s equally controversial world premiere performance where he favoured fast tempi has widened the debate about the interpretative choices in this work. Interestingly one of the most successful performances in the Slatkin cycle, which generally received lukewarm reviews, was Symphony No.9 which is played with greater drive and dynamism than many other versions.

In direct comparison to Sargent, Slatkin or Manze (in concert), Brabbins is unfailingly musical and intelligent but in so doing somehow underplays the questing originality of the score. Make no mistake this remains a wholly enjoyable performance and one that is as well-recorded as any but perhaps not the summation of this composer’s extraordinary creative life that I was hoping to hear. Reflecting on both this cycle and the one from Mark Elder, it does lead me to feel that, if there is going to be another survey of these glorious works it would be of greatest benefit if it were done by an orchestra and conductor not so steeped in the British performing tradition of these scores. Recently I have heard archive performances from Boston of Job and Symphony No.8 which blaze with a sense of discovery and revelation – now a cycle from Boston or perhaps a major German orchestra surely would be something rather special! The virtues of these Brabbins performances are many and commendable but ultimately they are dependably mainstream. Perhaps a little more of Vaughan Williams the exploratory rebel would have been more intriguing.

Nick Barnard

Previous reviews: John Quinn (March 2023) ~ Ralph Moore (March 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from