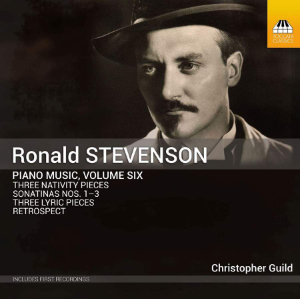

Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015)

Piano Music Volume Six

Sonatina No. 1 (1945)

Sonatina No. 2 (1947)

Sonatina No. 3 (1948)

Retrospect (c.1945)

Three Nativity Pieces (1949)

Three Lyric Pieces (1947-50)

Christopher Guild (piano)

rec. 2022, The Old Granary Studio, Toft Monks, Beccles, UK

Toccata Classics TOCC0662 [80]

Christopher Guild’s ongoing survey of Ronald Stevenson’s piano music (Volume 1 ~ Volume 2 ~ Volume 3 ~ Volume 4~ Volume 5) now looks at the compositions from the beginning of his career. He wrote much of this repertoire after his discovery of Ferruccio Busoni’s achievement, but before his relocation to Scotland in 1952. His biography appears on the Ronald Stevenson Society website.

Three rules of thumb help appreciate Ronald Stevenson. He was eclectic, prepared to use forms, scales and sonorities from around the world and without historical prejudice. He shared the aesthetic trajectory with piano virtuosi and distinguished composers (think Franz Liszt, Ferruccio Busoni, Percy Grainger, Ignacy Paderewski and Leopold Godowsky) who also made arrangements, transcriptions and fantasias of other people’s tunes. And, though he was born in Blackburn, Lancashire, he adopted Scotland as his home, and came to be influenced by that nation’s art, literature, politics and music.

This review has benefitted greatly from Christopher Guild’s comprehensive booklet essay, and from many quotations therein.

Writer and record producer Ateş Orga, who wrote about Stevenson’s piano music, called the three Sonatinas the “earliest piano works of significance” in his catalogue. I will not discuss the nature and technical demands of the sonatina. Suffice it to say, Maurice Ravel’s and John Ireland’s significant examples are anything but didactic, and most of Beethoven’s Sonatina’s are tough to play. Stevenson wrote his pieces when he was a student at the Royal Manchester College of Music. Orga writes: “These three Sonatinas are interesting for many reasons, not least for sowing the seeds of Stevenson’s art in embryonic form.”

Sonatina No. 1 has several passages of virtuosic pianism. Stevenson’s own programme note says that the first movement “shows some influence of Hindemith’s First Piano Sonata in its counterpoint, harmonic tensions and cadences […]”. Next: “The second movement’s chromatics and quartal chord-structures show features absorbed from an early acquaintance with Berg’s Wozzeck.” Assorted styles combine in the Presto finale, including a sea shanty in the Dorian mode, “perhaps the earliest indication of a Grainger influence in my work.” There are also jazzy syncopations and chromatic passages. The booklet notes mention references to the earlier movements, not always easy to spot without the score.

Paul Hindemith’s music may have also affected Sonatina No. 2, a piece hard to classify: is it neo-classical or – as critic Malcolm MacDonald (cited in the booklet) has suggested – neo-baroque? Despite the apparent angularity, the mood is piquant rather than dissonant. There is much beauty in passing, and some beguiling sounds in both movements. Christopher Guild has noted the scotch snaps in the opening Adagietto, which predate Stevenson’s move to Scotland and his absorption of many of Scotland’s musical fingerprints.

Sonatina No. 3, at more than sixteen minutes, is actually of sonata length. (About the time Stevenson wrote it, he was imprisoned for conscientious objection to National Service. He had served time in jails at Preston, Liverpool, Birmingham, and Wormwood Scrubs.) MacDonald describes the first movement as an “almost Mahlerian Funeral march”, which nods to the 1962 Passacaglia on DSCH. The mood lightens with a quicksilver scherzo which seems devoid of angst. This magic continues in the finale, although sounding much more sinister and sarcastic.

There is nothing challenging in Retrospect, an early work. The title may refer to the notion that this beguiling song without words was looking back to late-Romantic pianism and formal structures.

The Three Nativity Pieces have charm and innocence but are tinged with a feeling of regret. They refer to the gifts the Three Magi brought to the Baby Jesus: Gold, Frankincense and Myrrh. MacDonald suggested that the suite “recalls both Liszt’s Christmas-Tree Suite and Busoni’s Nuit de Noël”. Gold: Children’s March is “non-militaristic” in mood, typically jaunty and merry. The tune is based on the pentatonic scale, so black notes on the piano. The long and involved Frankincense: Arabesque musically represents the elaborate design of intertwined figures or complex geometrical patterns, frequent in Arabic architecture. Here it creates more than a hint of the exotic, complete with drifting clouds of incense. Myrrh: Elegiac Carol is based on the piece So she laid him in a manger, a carol that Stevenson wrote in 1948. He set the words by the Tyneside blast-furnaceman J.H. (Joe) Watson, a friend of D.H. Lawrence and founder of the Frating Hill Farm near Colchester. This socialist institution had been set up to provide farm labour so that pacifists, as conscientious objectors, could remain within the law. After a lugubrious opening marked angiosca soppressa (supressed angst), the transcription of the carol follows. This is elaborated before the sombre opening theme returns.

Chorale Prelude for Jean Sibelius, one of Three Lyric Pieces, was begun when Stevenson was incarcerated in Wormwood Scrubs. The piece reflects his admiration for the Finnish master, whom he regarded, according to Ateş Orga, as “a lighthouse amid the maelstrom of post-War contemporary music”. Equally at odds with the prevailing musical temper is the Andante Sereno, with its “emphasis on melody”. There are touches of gentle dissonance here and there, caused by clashes of the Ionian and Lydian modes, but “serene” is a fitting title. Christopher Guild correctly writes that the “sonorities achieved […] are most distinctive for piano music of this era, especially in Great Britain”. The opening bars of Vox Stellarum (Voice of the Stars, or Cosmos) are impressionistic in the evocation of vast universal spaces. The composer wanted “to reflect a girl’s singing”. He drew on Scotticisms in the middle section, once again using the pentatonic scales.

Christopher Guild is a powerful advocate for Ronald Stevenson’s piano music. He brings technical proficiency to the performance and scholarly endeavour to the liner notes. The sound recording is ideal, and the programme lasts a remarkable 80 minutes.

I understand that Volume 7 is “in the bag” and further releases are at the planning stage. Listeners should not forget Guild’s contribution to Scottish music: his recordings of Francis George Scott, Ronald Center and William Beaton Moonie.

John France

Help us financially by purchasing from