Music for Strings

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1910; rev. 1919)

Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

Concerto for String Orchestra (1938)

Frederick Delius (1862-1934)

Late Swallows (1916-17)

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Introduction and Allegro for Strings, Op. 47 (1901, 1904-05)

Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

rec. 2022, St. Augustine’s Church, Kilburn, London

Chandos CHSA5291 SACD [66]

Two previous issues from Chandos of the Sinfonia of London directed by John Wilson have been among my “Recommended” (review; review) recordings and my Records of the Year 2022, so I had high hopes for this latest release of four pieces of English string music, all from the earlier part of the 20C. There was also the added interest for me of not being acquainted with either of the two lesser-known works sandwiched between two great string orchestra stand-bys. Those two favourite works have enjoyed so many recordings, including classics by Barbirolli – with the old Sinfonia of London! -that wheeling them out yet again might be something of a risk, but the advantages here of this new recording are those of the best and latest digital sound, an interesting programme matching the tried-and-tested with the more recherché and capitalising upon a reputation derived from a growing catalogue of critically acclaimed recordings of the kind I recommend above.

The Tallis Fantasia is played with great poise and warmth and the balance between the two antiphonal groups is perfect, the smaller group sounding suitably removed yet clearly delineated, just as the soloists emerge from the polyphony with great purity. A trademark of the Sinfonia is the care with which they grade dynamics in unison; it is such a homogeneous and coordinated band.

The work is taken slightly faster than usual, lending a new urgency and momentum which is by no means inappropriate; this is music not necessarily in “pastoral idyll” mode throughout but rather suffused with unresolved tensions; only in the last, endlessly prolonged diminuendo G major chord is there resolution.

The influence of the 18C concerto grosso – especially those by Handel – is highly discernible in all these works but in Howell’s case autobiographical factors came into play. Primarily known for his Anglican church music, Howells nonetheless wrote in many other genres, including large-scale orchestral works such as this Concerto for String Orchestra in which he aimed to achieve “a unity of the two supreme fellow-English composers many of us have seen and known in our time” – hence the link with Elgar and Vaughan Williams on this disc. Howell began work on the concerto as a tribute to Elgar after his death in 1934 but the theme of grief was intensely compounded by personal calamity, when in 1935 his nine-year-old son died.

It is here played with great vigour and precision and its debt to the Elgar which concludes this programme is – at least to my ears – much in evidence but there is more conflict and even anguish here, underlined by the crisp precision of the playing. The central viola solo, set against a haunting tremolando backing, offers little comfort; indeed, this is restless, jagged, uncomfortable music, especially when set against its companion pieces. Unlike the first movement, the passing allusions to the slow movement of Elgar’s First Symphony serve more to emphasise the disjuncture between the two pieces of music than any kinship; the aching beauty of Elgar’s Adagio is replaced by an agonised threnody. Occasionally the music takes refuge in a consoling E major but soon relapses into despair and the C major tacked-on ending sounds to me emotionally entirely unconvincing. The scrambling finale is expertly executed, Andriy Viytovych’s mellow solo viola makes a third, brief appearance and the concerted pizzicato passage evinces great virtuosity; just before the conclusion, we hark back to the despondency of the second movement. Everything is beautifully played but this spiky music does not much engage me. Given that this work -a brave choice – takes up nearly half the programme, your response to this music will play a vital role in deciding whether you want to acquire the recording.

Late Swallows is Eric Fenby’s orchestration of the third movement of Delius’ String Quartet, in accordance with Barbirolli’s suggestion for celebrating Delius’ birth centenary. It is typically soupy, soaring and dreamy – and its mood comes as something of an antidote to the preceding work; it is most elegantly played but I cannot say I find it especially memorable.

The Elgar piece is played with great verve and assertiveness but just occasionally I feel that the pauses and emphases have a certain self-consciousness about them; for purpose of comparison, I played the Barbirolli and despite its slightly inferior sound, I found in it an ease, flow and naturalness absent from this sparkling, cut-diamond account under review. There is simply more ebb and flow, more heart, in that vintage account. The conclusion to this new recording, however, is glorious, its depth of bass sound especially gratifying.

I have defaulted throughout this review to reiterating how flawless the playing is; my reservations centre not upon the artistry here or the quality of the engineering, but rather the desirability of the programme. My own feeling is that already possessing fine recordings of the works here to which I respond, I am not especially enraptured by it.

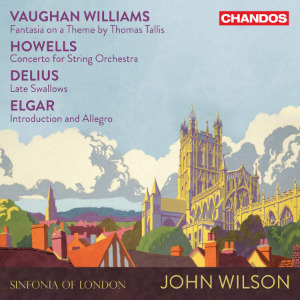

This recording is completed by full notes by Andrew Burn translated into German and French and an attractive period-30s-poster cover featuring Gloucester Cathedral, reminding us of the Three Choirs Festival and its connections with famous English composers. The notes about the Sinfonia even include a quotation from Nick Barnard’s admiring review of their recording of Respighi’s Roman Trilogy. John Quinn reviewed it equally enthusiastically – kudos to my MusicWeb colleagues!

Ralph Moore

Help us financially by purchasing from