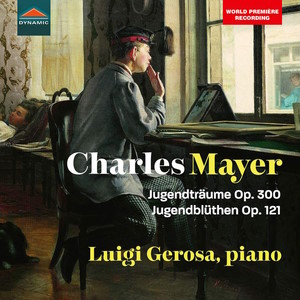

Charles Mayer (1799-1862)

Judendträume 6 tone pictures Op.300 (first pub.1860)

Jugendblüthen Op.121 (first pub.1849-50)

Luigi Gerosa (piano)

rec. 2022, Griffa Studio, Milan

Dynamic CDS7980 [79]

It is always nice to fill in a vague pencil sketch of a composer and Charles Mayer is one of the those shadowy figures of whom I have had but the tiniest glimpse; a banal little Military March, perhaps a minute long, played many years ago on Radio 3 and one paragraph in Harold Schonberg’s the Great Pianists in which he is described as a pianist with a good European reputation…who settled in St Petersburg. There he had played and taught – and had not once been asked to play at court. It was the only thing he wanted in life…and then in strides the younger virtuoso Adolf von Henselt who immediately becomes Court pianist!

Dynamic have amply fleshed out this picture of Charles Mayer with this release of two of his numerous collections of short piano works. The booklet opens with what can only be huge understatement; not few are the composers…whose current popularity is far from what they enjoyed during their lifetime. In the case of Mayer his popularity could hardly be less and attractive though these pieces are it is unlikely to help him claw his way back into the public consciousness.

He was born in Könisberg on the Baltic coast in Prussia but his parents soon moved to Moscow, via St Petersburg and it was there that he studied with the esteemed Irish pianist John Field who had made his home in Moscow in 1807. Mayer toured across Europe with success and began to compose, eventually producing some 350 opuses, pretty much exclusively for the piano and including études, caprices, valses, opera fantasies and two concertos – everything the touring virtuoso needed. After the appearance of Henselt in Russia he evidently decided enough was enough and moved to Dresden where he spent the rest of his life.

His Jugendblüthen – Flowers of Youth – comprises 24 short character pieces in much the same vein as examples by Schumann, his Kinderszenen or Album for the Young, Mendelssohn in his Songs without Words and Children’s Pieces op.72, Tschaikowsky’s Album for the young and so on. There are many charming moments within its 96 pages – the little polka danced by die junge Tänzerin (no.4) and it’s high-stepping cousin die junge Virtuos (no.14), the agile tarantella (no.2) – these are pieces about youth rather than pieces for children to play after all – the scherzo (no.6) that echoes Mendelssohn’s Rondo capriccioso op.14 very effectively and several pieces that could easily be songs without words – the lilting barcarolle (no.7), little May flowers (no.12), the attractive Notturno (no.22) and an actual Song without words (no.5) just to name a few. Trinklied (no.3) is a rather odd choice for a childrens’ collection but everything else here fits the bill nicely. I like the two part Leid und Freud – étude mélodique with its melody swathed in arpeggios and its scurrying middle section and if the Demons in no.17 – capriccio infernale – are a relatively polite bunchand the folk dancing in Norwegischer Tanz (no.21) is quite restrained it does not detract from the imagination and melodiousness of these pieces.

A decade and 179 opuses later we have the six pieces that make up Mayer’s Judendträume. The format is much the same with a series of short character pieces but I feel these are higher quality works; certainly the opening piece, Traumbild, with its echoes of the Schumann of the arabesque is a piece I am eager to learn. Its long yearning melody rides easily over a restless accompaniment that continues even in the more open hearted central section. Mayer’s melodiousness is again apparent in the Mendelssohn-like Sehnsucht though the yearning of the title is less mournful and this is something of a spring song in nature. The finale of his rival Henselt’s F minor concerto came to mind with the third piece Das Stürmische Herz, stormy indeed though it does not quite share its phenomonal difficulties. Ungarsische Weise is a jaunty Hungarian dance, more for the ballroom than a Magyar camp perhaps but entertaining nevertheless while Heiterer Sinn is indeed cheerful with a vaguely Schubertian melody and triplet figuration to add spice. After an equally melodic middle section the triplets return for an excitingly virtuosic coda. The final piece is Rose bud which is a robust little dance in A minor with an attractive central melody and plenty of graceful right hand figuration.

Both of these sets, especially Jugendträume amply demonstrate the quality of the writing that can be found among some of the 19th century’s forgotten figures and though there is unlikely ever going to space on recital programs or live audience to hear them it is nice to have the opportunity to let a small part of Mayer’s muse live again. Italian pianist Luigi Gerosa plays these pieces very sympathetically though I feel he responds better to the more serious Jugendträume where his phrasing is more flexible and he seems more relaxed in his rhythms. I would have liked more agitato in the allegro agitato of the toccata op.121 no.8 which seems a bit too steady and doesn’t slow down for the more graceful A major central section which should be meno mosso. Perhaps the melody of no.12 Maiblümchen could haveridden above the triplet accompaniment a little more too but he is full of character in pieces like Die Dämonen (no.11) and Neckereien – banter/teasing (no.19)andoverall these pieces come across very well. I have previously enjoyed his other recording of rare music for children by Stephen Heller (Dynamic CDS7747).

Rob Challinor

Help us financially by purchasing from