Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Symphony No. 1 in E flat, K16 (1764-5)

Symphony No. 28 in C, K200 (1773-4)

Symphony No. 41 in C, K551, Jupiter (1788)

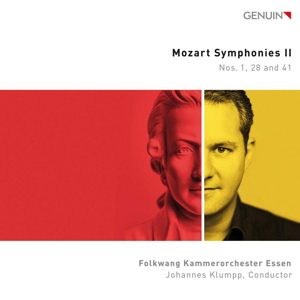

Folkwang Kammerorchester Essen/Johannes Klumpp

rec. 2019/21, Villa Hügel, Essen, Germany

Mozart Symphonies II

GENUIN GEN22783 [72]

In Symphony 1 Mozart begins Molto allegro, a man’s loud tutti theme followed by a lady’s soft sustained chords of languor, a contrast Johannes Klumpp might have made even stronger. The man next tries a few bristling tremolando flourishes in the second violins and violas. The lady counters with a pleasant second theme (tr. 1, 0:46) over a busy cellos and double basses’ staccato descent, in the theme’s second part (0:55) merrily taken up by the first violins beneath glowing chords on the oboes and horns. Add tremolando in the violins and an octave rise and the excitement intensifies before a codetta (1:17) of light, jocular lady and loud, tub-thumping man. The development has the man again firing tremolandos, the lady (2:50) charmingly reprising the second part of the second theme, sweeter a fourth higher (3:39), silkily delivered by the Folkwang Kammerorchester first violins, an amazing achievement for an eight-year-old composer.

I compare the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra/Roger Norrington recorded live in 2006, also presenting Mozart symphonies from different periods (Hänssler 93.211). He’s more mellow and courtly, the string-bass lurking rather than Klumpp’s power centre. Norrington’s wind chords are cosier repose, Klumpp’s strings’ tremolandos more shivering.

The Andante slow movement is gently pulsing strings and rising and falling repeated motif in the string-bass over which wind chords indolently luxuriate. A loud climax is attained quite early (tr. 2, 2:33) in the second part. Timing at 4:42, Klumpp’s Andante vegetates in comparison with Norrington’s 3:35, which has a clearer sense of direction. Norrington balances the wind and strings better: Klumpp’s wind overpowers the very soft strings. Norrington has the string-bass clearer by using bassoon. Klumpp makes more of the climax’s quick, unexpected arrival.

The Presto finale sports a rondo theme with an energetic rising phrase, the lady, then a restraining falling one, the gentleman. In the first episode (tr. 3, 0:20) the lady’s more reflective approach to the falling phrase is thrust aside by the barnstorming man’s scooping tutti octave ascents with demisemiquavers. In the second episode (0:56) the lady introduces a soft rising phrase of surprisingly luminous cast, immediately commandeered by the loud man. Timing at 1:15, I prefer Klumpp’s more evident Presto than Norrington’s 1:37 and will sacrifice the clarity of some of Klumpp’s strings’ semiquavers for his more rumbustious effect.

Symphony 28 opens with an Allegro spiritoso contrasting a loud, descending masculine phrase of command with a soft, descending feminine phrase. In the next tutti the man parades a heroically rising second strain bolstered by violins’ tremolando; the lady counters with a second theme (tr. 4, 0:38) showing her gentler violins can articulate the elegance of dance, enjoyment of demisemiquaver frills and end on a stretched appoggiatura like a long wink (0:47). The exposition codetta (0:57) has the man reasserting himself, but the lady continues to make her quieter presence felt (1:08). Klumpp well contrasts a vibrant male and stylishly demure female presence. Yet the development’s lady doggedly maintaining sequences of a familiar rhythmic pattern (2:47) makes her seem weaker. Luckily the recapitulation has her fully contented as the coda ends with ten loud male chords. Klumpp, timing at 6:49 against Norrington’s 7:30 (Hänssler 93.216), is slicker, more spiritoso, but sometimes Klumpp’s violins sound too soft and therefore reserved, in particular in interplay (0:41) with the oboes in the second theme. In full cry in tremolando in the tuttis his violins are splendid. Norrington’s bonus is a realized timpani part to match the trumpets and horns in the man’s music, but Klumpp’s crisp chords have plenty of grandeur.

In the Andante slow movement, the lady’s muted first violins find warm repose bathed in the muted second violins’ running semiquavers, but the man intemperately has the first violins bring loud demisemiquavers punctuated by oboes and horns to wake her up (tr. 5, 0:19). Klumpp should be louder here. The lady remains daydreaming and reaches a wistful phase. The man’s response finishes with a bold, ‘Pull yourself together’ rising statement. The lady begins the development (2:53) pondering a soft version of the man’s theme and finds it lacks substance, making the man’s retort tetchier. The recaps maintain the original divergence, but you feel the lady has won this argument with better music.

The Allegretto Minuet begins sunnily blazing in a loud tutti headed by oboes, horns and trumpets in the man’s camp; but the horns join the lady with a soft echo of the closing four notes and her response is double the length. The man wants everything clear-cut; the lady is content to consider and expand. At the end of the second strain the man assentingly echoes her final phrase and everyone is happy. In the Trio for strings alone (tr. 6, 1:46) the lady takes the dotted quaver + semiquaver dance rhythm that was the man’s initiative late in the Minuet. In the second strain the man tries to make this more bullish, whereupon the lady stylishly ignores him.

The Presto finale is played with great verve by Klumpp. The lady’s soft skittering replete with dotted quaver trills and demisemiquavers is punctuated by the man’s loud four chords on oboes, horns and trumpets. As the latter continue, the lady becomes full-throated in tutti strings’ loud running quavers. The mood becomes festive and, as played here, suddenly sounds amazingly 20th century (tr. 7, 0:14). The second theme, proposed quietly by the lady (0:25) is undeniably 18th century, both delicate and optimistic, though the ensuing tutti has lady and gentleman both maintaining their divergent characters without blending. The development (1:53) follows the same pattern but the coda (4:32) makes a Mannheim rocket of the lady’s quaver runs, quickly rising from p to ff, as the man’s chords finally join them and both exit in triumph.

In Symphony 41 the male versus female dialogue is more condensed and integrated. The opening phrase is a military motif: a cannon tutti firing on C. The second phrase, gently rising and gliding, is the lady’s suave ‘Relax!’. The second theme (tr. 8, 1:22) is the lady all elegance, while her opening three-note motif on first violins is immediately echoed by cellos and double-basses, the man straightway responding affectionately, enhanced by his later taking up the lady’s opening phrase (1:45). The third theme (2:29) has the lady’s happy tripping melding into a tutti celebration with the man. Klumpp does this very well. Norrington (Hänssler 93.211) has a show of blasting force for the man. For Klumpp this isn’t necessary as man and lady are more congenially matched than usual: the timpani can be crisp and clear without thrashing. There’s a fake recapitulation (6:51), the lady softly echoing the man’s opening phrase which then gets a proper developmental shake-up to show what might happen in a less companionable environment.

The Andante cantabile slow movement, with muted violins, starts as the lady’s musing search for relaxation. But how strictly should the loud tutti chord be played after the lady’s first phrase? If strictly, as Klumpp, is this now a belligerent man’s exclamation? When the phrase is repeated just by the cellos and basses (tr. 9, 0:47) it’s still a retort but mollified by the consolatory warmth of the loud intervening tutti. The man’s unease is explained by the pain of the second theme, with sfp when its opening chord is reached (1:17) and similar dynamic contrasts thereafter, faithfully clarified by Klumpp. Then, with the third theme (1:55) the lady offers support, but with more tender softness than Klumpp provides, before the second part of the theme’s six times repeated seven-note motif of affectionate nostalgia (2:11). The development (6:10) reintroduces the troubled second theme, but Klumpp is now less convincing in its tension, perhaps because another seven-note motif (6:54) from the exposition (2:42), repeated eleven times, diffuses the torment to allow the recap. Norrington, timing at 9:14 to Klumpp’s 10:12, achieves a tenser second theme in the development, though his seven-note motif in the second part is less endearingly soft. His lady’s opening theme has more character, that of indulgent sighing progressing more sorrowfully, provoking the man’s second theme.

The Allegretto Minuet the lady starts as a soft, graceful dance; the man transforms the second part of its first strain into a loud proclamation. The same contrasts, arguably overcooked by Klumpp, are in the second strain (tr. 10, 0:35), where more interesting is the lady’s freer dancing exploration, later coming from just flute, oboe and bassoon (1:04). In the formal Trio (2:10) soft flute, bassoons and horn cue in jovially skipping oboe and first violins while in its second strain (2:27) a loud tutti flexing of heroic aspiration is softly shortened and echoed by first violins then ousted by the first strain repeat. Norrington is smoother in the lady’s but bludgeoning in the man’s music. I’d prefer both more dance-like, for which go to the Danish National Chamber Orchestra/Adam Fischer of 2013 (Dacapo 6.220639) who instil inherent lightness without loss of vibrancy in the loud passages.

In the Molto Allegro finale the lady increasingly favours a serene, contemplative approach, the man a majestic, heroic one. But both blend in a peroration of great variety and ingenuity. There are six themes. Theme 1, the opening four notes, Mozart’s self-quotation from his Missa brevis, K192 (1774), ‘Credo, Credo’ (‘I believe’) as sung. Theme 2 (tr. 11, 0:10), a continuation in the same mass, the first eight notes set to ‘In unum Deum’ (‘in one God’), these latter a major generating force in the exposition climax (1:29). Theme 3 (0:15), a lively descending motif. Theme 4 (0:44), a six-note rising motif. Theme 5 (0:57), a soft, musing transformation fusing elements of themes 1 and 3. Theme 6 (1:03), a staccato four-note motif. The development (4:05) brings more rumination on the first theme, a battle with the third, the latter transmuting into a rising motif (4:14), returning to a falling one to signal the recap (4:59). Five themes are combined in the coda from 9:32, straightaway themes 1 and 5, theme 4 at 9:36, I can just about hear theme 6 (9:44) and theme 3 (9:52), but Klumpp is right to concentrate on the apotheosis of the first theme in effulgent high tessitura from flute, oboes and first violins. Theme 3 dazzles in the codetta (9:57) which reintroduces theme 2, not heard in the combination, followed by theme 3 (10:01). Klumpp brings great gusto to it all and achieves an exhilarating sound. Norrington, timing at 11:27 to Klumpp’s 10:15, is less Molto Allegro, less exciting, yet supplies more elegance and engaging merriment.

Michael Greenhalgh

Help us financially by purchasing from