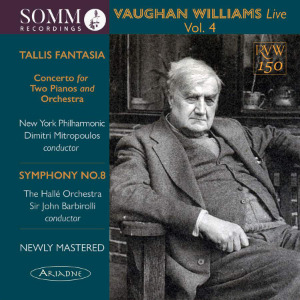

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Vaughan Williams Live – Volume 4

Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1910)

Concerto in C major for Two Pianos and Orchestra

Symphony No. 8 in D minor

Arthur Whittemore & Jack Lewis (pianos)

New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra/Dimitri Mitropoulos

Hallé Orchestra/Sir John Barbirolli (symphony)

rec. live, 29 August 1943 (Fantasia), 17 February 1952 (Concerto), Carnegie Hall, New York; 15 May 1964, Free Trade Hall, Manchester (Symphony)

AAD

SOMM Recordings Ariadne 5020 [72]

I’m running a little out of sequence with SOMM’s invaluable ‘Vaughan Williams Live’ series. Along with colleagues, I’ve already greatly admired Volume 1 and Volume 2, but I haven’t yet completed my review of Volume 3, which has already been appraised in great depth by Nick Barnard (review). Volume 4 presents its own fascinations. There’s a live account of the Eighth symphony by Barbirolli. However, the VW credentials of ‘Glorious John’ are widely known; so, let me first focus on the performances conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos.

I’m a great admirer of the volatile talent of Mitropoulos, not least his searing performances of the music of Mahler. The music of Vaughan Williams was by no means central to his repertoire, but he conducted a few of the English composer’s works. He made an incandescent recording of the Fourth Symphony for Columbia in January 1956. In his 1995 biography of the conductor, Priest of Music. The Life of Dimitri Mitropoulos, William R Trotter references a 1944 performance of A ‘London’ Symphony during Mitropoulos’s time as the chief conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and he also programmed the Sixth in Minneapolis. He did the Fourth in early 1943, when he guested with the New York Philharmonic and he kept it in his repertoire; for example, it was one of an array of scores which he and the NYPO played in Edinburgh in 1951. However, Trotter does not mention either of the two VW works included on this disc.

There are two Mitropoulos versions of the ‘Tallis’ Fantasia immured within a huge box of his recordings for RCA and Columbia (review). One was made with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and the other with the New York Philharmonic. I imagine the latter is the version that I have on an old Sony Classical disc, which also contains the aforementioned recording of the Fourth Symphony (SMK 58933). That ‘Tallis’ recording dates from March 1958 and I’ve never cared for it much. Mitropoulos despatches the work in a mere 12:44. How different the present live version is. The recording plays for 17:26, though the actual performance is slightly shorter; SOMM have retained a small amount of applause and the brief radio announcement, from which we learn that the piece opened the programme. Mitropoulos’s performance is notable for its breadth and warmth; I liked it very much. As I listened, I marvelled at the quality of the 80-year-old sound. I don’t know what source Lani Spahr had for this off-air recording but his restoration alchemy achieves amazing results. For example, when the second orchestra makes its first contribution (4:40) the differentiation from the main ensemble is clear; it’s also noticeable how sweet-toned is the playing. The ruminative viola solo (6:54) ushers in a series of fine contributions from the solo quartet; their names are unknown. The climax of the piece is uncommonly passionate and urgent. This is a performance of quality and we can enjoy it in astonishingly good sound.

For the concerto, Mitropoulos had as his soloists Arthur Whittemore (1915-84) & Jack Lewis (1916-96). Simon Heffer tells us in his very useful notes that they teamed up as a duo in 1940 while they were students at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester. What he doesn’t say is that these two pianists gave the US premiere of VW’s concerto in 1949 and then went on to make the first recording of the work the following year. I hasten to add that I only know this because the information was contained in the booklet of an Albion Records disc which included that 1950 recording (review). Their interpretation must therefore be considered authoritative. Though, unsurprisingly, the studio sound on the RCA/Albion recording is better, this 1952 broadcast has come up pretty well in Lani Spahr’s restoration and the performance is well worth hearing. It’s also a noteworthy occasion because we learn from the closing radio announcement that this was the US broadcast premiere of the work. (So, Whittemore and Lewis might be said to have achieved a full house: US premiere; US broadcast premiere; first commercial recording of the work.)

The opening ‘Toccata’ has a good deal of brilliance and energy about it in this performance. The pianos are given due prominence in the aural picture but the orchestral contributions can be heard well enough. The sound is somewhat bright but that’s understandable in a recording of this age and, in any case, I think VW’s writing has a lot to do with the brightness. The second movement, ‘Romanza’, follows without a break. Here, the pianists find the poetry at the start of the music and when the orchestra joins in they play with sensitivity. The movement is a beautiful composition, belying the (unfair) perception in some quarters that this concerto is a “percussive” piece; the present performance does the music justice. The last movement is something of an odd construction. The opening section ‘Fuga chromatica’ calls for – and here receives – great virtuosity from the soloists and from the orchestra. The music is full of steely brilliance and reminds us that, in its original form for solo piano, the concerto comes from the same period in VWs career as Job and the Fourth Symphony. After all that virtuosic bustle, the second section, ‘Finale con tedesca’ takes us into somewhat calmer waters; eventually, the soloists lead the way into a conclusion which, given the brilliance of much of the preceding music in the first and third movements, is surprisingly tranquil. The soloists are, as I suggested earlier, authoritative; they exhibit great familiarity with the music. Mitropoulos and his orchestra give them splendid support in what must have been very unfamiliar territory for the players.

The Hallé Orchestra of 1964 would surely have been familiar with VW’s Eighth Symphony. After all, the score was dedicated to their chief conductor, Sir John Barbirolli who led them in the first performance of the symphony in May 1956. The following year, they made the first recording of the work (review). The performance preserved here comes from a few years later in the symphony’s performance history, From the closing announcement, delivered in the exquisitely modulated BBC tones of the time, we learn that it was the closing work in a programme recorded for broadcast (without an audience?) in the Free Trade Hall.

Under Barbirolli’s guidance, the Hallé plays all the variations that comprise the first movement very well. Did VW design this movement as a showpiece? Maybe not, but it certainly gives an orchestra plenty of opportunity to show their collective prowess; that’s what happens here. The woodwind and brass have the floor to themselves in the Scherzo. The present performance is lively and colourful. In the Cavatina the strings play with the warmth and expressiveness that you’d expect in a Barbirolli-led performance and the recorded sound doesn’t let the players down. Finally, VW throws in all manner of percussion instruments in his celebratory finale. Barbirolli and the orchestra offer a performance that is disciplined – of course – but which sounds as if everyone is having fun.

Once again, Lani Spahr has worked his magic on these recordings. As you’d expect, the best sound is to be heard in the symphony recording – after all, that’s a mere 59 years old (nearly) at the time of writing. But the two Mitropoulos recordings, which are much older, have come up remarkably well; listening to both of them is a pleasant experience. I think it helps that Mr Spahr is a performing musician of no little eminence; consequently, I suspect he knows just how far to go in order to produce restorations that are not just technically impressive but which are musically satisfying too. This series has been seriously impressive in terms of the audio results and this final volume in the series maintains that high standard. I say “final”, but though the VW 150th celebrations are now behind us I’m sure collectors would be delighted if Lani Spahr and SOMM were able to put some more historic performances of this great composer’s works into circulation.

The series has benefitted from excellent booklet essays by Simon Heffer; he has contributed another valuable commentary to accompany this release.

John Quinn

Previous review: Nick Barnard (March 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from