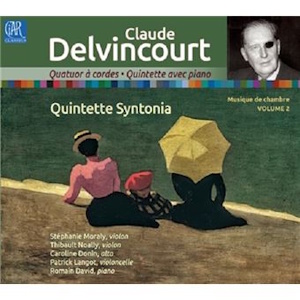

Claude Delvincourt (1888-1954)

Chamber Music Volume 2

String Quartet (1947-1954)

Piano Quintet (1908)

Quintette Syntonia

Romain David (piano)

rec. 2022, Auditorium Marcel Landowski, Paris

Ciar Classics CC016 [63]

Perusing the list of CDs for review I was surprised to find a name new to me. Claude Delvincourt was a French composer who was a younger contemporary of Debussy and Ravel and twice winner of the Prix de Rome. The relevant disc was Volume II of an exploration of his chamber music, so it had to be heard!

As a child, Delvincourt was something of a pianistic prodigy. Entrusted, at a young age, to the teaching of Léon Boëllmannand Henri Büsser, he was good enough to be invited – at the age of just nine – to perform in front of the Queen of Romania. He entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1906 and studied under Caussade and Widor, whilst simultaneously studying at the Faculty of Law (because his parents regarded it as important that he should have the means to follow his father’s diplomatic career). Music was, nevertheless, to take centre stage in his life and he focused on composition and teaching, eventually being appointed to the directorships of the Conservatoires of Versailles and Paris in 1932 and 1940, respectively. His compositions included a wide range of vocal and choral works, a small body of solo instrumental music, incidental music, film scores and other orchestral works. The last category included symphonic poems, orchestral suites and a Piano Concerto of 1954, unfinished at his death, but no symphonies.

If the works on this disc are representative, Delvincourt was not a follower of the school of Debussy or Ravel. His Quintet for Piano and Strings was written in 1908 for the Concours de la Societe des Compositeurs and, as one might expect, the influence of Franck is evident and – to a lesser extent – that of Vierne and Faure, rather than the impressionists. Although Florent Schmitt’s sprawling piano quintet actually won the prize, there is a lot to be said for that of Delvincourt, which does not sound like a student work. There are four movements. The note writer points out that, in Delvincourt’s early chamber pieces with piano, that instrument predominates “outrageously” and is “almost like a concert soloist”. The opening page or so of the first movement (Allegro agitato) herecorrespondingly starts with a considerable piano flourish but, after this, the piano subsides and integrates with the strings to announce the principal theme. A second subject is memorable by being vaguely comical. Thereafter, there is plenty of variety of texture, keys, dynamics and forward momentum as the music develops the two themes – certainly enough to keep the listener’s interest.

A delightfully bouncy Vivace Scherzando follows that half brings to mind pieces by Dvorak and Saint-Saens as seen in a rather hazy mirror. The slow Andante Espressivo is reminiscent of Chausson and sounds somewhat longer than it actually is – eventually slowly fading to a quiet conclusion. Finally, we are given an innovative Allegro agitato finale, which seems to be built around something like the main theme from Lalo’s orchestral Scherzo – originally his Piano Trio No 3. This is seen out by a long and loud Maestoso section before a short Allegro molto coda.

The String Quartet was Delvincourt’s last completed composition before his untimely death in 1954, at the wheel of his car. He had written the work for the Parrenin Quartet and never heard it – since he sadly passed away just a few hours before their first performance of it. The quartet actually opens the disc and, expecting the kind of music provided by the Piano Quintet, I was a little shocked to be assailed by the “martial aggressiveness” of the opening movement (Allegro molto con veemenza), which starts with an almost serial theme – certainly vehemently! Evidently, the composer’s compositional style had evolved considerably since his early works, possibly influenced by Berg. This evolution sounds similar to that occurring on the other side of the channel in the contemporary style of Frank Bridge – as exemplified by the stylistic change between, say, his ‘Cello Sonata and his Third Quartet. In fact, the note writer himself alludes to a Berg connection – in that Delvincourt’s work is possibly based on “a secret program”, like that of Berg’s Lyric Suite.

Despite all this, Delvincourt hadn’t lost the knack of being interesting – as is evident from the second movement Presto’s multiple textures and techniques – building around “a popular-sounding air with a disarming naivete”. The enigmatic third movement Adagio estatico opens with “a halo of harmonics”. It has a poignant and other-worldly atmosphere but doesn’t seem to be going anywhere in particular. Eventually, it builds to a loud climax before disappearing into the ether. The last movement Allegro agitato starts in a similar vein. It has some of the grating sarcasm of Shostakovich before the “popular air” of the Presto returns, transformed, and the quartet ends peacefully but ambiguously.

These are not quite master works but they are fine pieces and they deserve to be heard more. Perhaps this premiere recording of the quintet will help to achieve that. Performances are excellent. The recording is a little dry and not ideally resonant, but it is very acceptable. Beware, however, of the very high recording level – which might come as a shock if you have the volume setting high when the music commences. The extensive notes in French with an English translation provide a comprehensive analysis of the music, but are rather florid and somewhat hard work. The whole is packaged in one of those cardboard sleeves that seem to be favoured by the French.

Bob Stevenson

Previous reviews: Jonathan Woolf (November 2024) ~ Stephen Greenbank (November 2024)

Availability: Ciar Classics