William Baines (1899-1922)

Pictures of Light

Paradise Gardens (1918-1919)

The Naïad from Three Concert Studies (1920)

Silverpoints (1920-1921)

Tides (1920-1921)

The Island of the Fay (1919)

Pictures of Light (1920-1922)

Eight Preludes (1920-1922)

Five Songs (1919)

Robin Walker (b. 1953)

At the Grave of William Baines (1999)

Duncan Honeybourne (piano)

Gordon Pullin (tenor)

rec. 2022, Holy Trinity Church, Hereford, UK

DIVINE ART DDA25234 [78]

What a remarkable talent William Baines was. He composed at a ferocious rate; a forty minute symphony when he was seventeen, numerous movements and works for string quartet, a handful of songs all crowned by around 150 piano pieces. But he was dead eight months after his twenty third birthday. During his brief life, and certainly in the years following, his genius was recognised and even into the 1950’s performers were advocating for his music. I first became aware of him – as I guess did many others – through the Lyrita LP performed by the ever questing and indefatigable Eric Parkin in 1972 – presumably to mark the 50th anniversary of his death. Given the calibre of the music it is slightly surprising and depressing that 50 years later in the centenary year there has actually only been further complete disc devoted to Baines (also from Parkin but on the Priory label) in 1995 where curiously and disappointingly for collectors the repertoire was nearly exactly copied from the first disc with a couple of very brief exceptions. Since then Alan Cuckston shared a (very good) disc with music by Eugene Goossens but apart from single works appearing on recital discs that is just about it.

Which is a surprise because this music is never less than very attractive, certainly individual and always intriguing. The music of the French Impressionists is a fairly undigested influence – certainly the innocent ear would guess a continental provenance before a British one. But Baines was a very young man and more remarkably essentially self-taught so there is a passion and a sincere spontaneity to this music that cuts through any accusations of derivity. As such this new disc from Duncan Honeybourne is to be warmly welcomed. Honeybourne has an impressive discography already especially in the field of less well known British piano music. I have enjoyed his collections of John Joubert’s complete piano works and especially the remarkable Christopher Edmunds’ Piano Sonata – one of several recordings for EM records. Here he is perfectly attuned to the complex sound world of Baines’ keyboard writing and has the technical resources to deal easily with the intricate and demanding aspects of the music too. The only slight disappointment is that of the solo piano works only the Eight Preludes [collated from various manuscripts by Robert Keys after the composer’s death] are new to the catalogue. These are different works from the Seven Preludes recorded twice by Parkin. The disc opens with Paradise Gardens which is – a relative term – Baines’ most famous work and is the one that appears in every recital and programme. Certainly it embodies both his aesthetic and musical style – the fact he was just nineteen when he wrote it is all the more remarkable. Honeybourne is significantly more languorous than any other performance I have heard but effectively so.

What emerges from the disc as a whole is that the music – as interpreted across the different discs – can support a diverging range of styles. This is a sure sign of musical substance. Another feature reinforced by this new recital is how at home Baines is writing for the keyboard. By all accounts he had large hands and an individual technique but there is a strong sense that he intuitively understood keyboard writing. Several of his piano scores can be viewed on IMSLP here including most of this recital. The eye confirms what the ear hears – this is complex yet confident writing quite different from the far more generic symphony which is yet to receive a professional performance but can be heard in a rather ropey but committed performance on YouTube by an amateur orchestra. Very clearly the teenaged composer is ‘working out’ how to write for an orchestra – and failing more often than not! – in a way he does not on piano.

Yes of course Debussy casts a very substantial shadow over nearly all this music but in comparison to other British composers at this time – with the possible exception of Cyril Scott – I cannot think of another who so successfully embraces the potential of Impressionism in their scores. The sadness and frustration must be the thought of what might have become as Baines developed his own voice further as he matured as a composer. In effect this is his juvenilia and by that measure it is the equal of any. Honeybourne includes the powerful and brooding pair of pieces that makes up Tides and the three works of Pieces of Light that give the disc its title (and were included by Cuckston as well) are just ravishingly beautiful. The previously mentioned Eight Preludes are in the main very brief, some almost fragmentary. Honeybourne contributes a useful liner about the music and he states that the surviving manuscripts lacked performance directions which makes one wonder if they were first drafts or work in progress. Whatever the truth of that they are valuable for the Baines enthusiast as in part they do suggest how the composer was expanding his musical vocabulary.

Also new to the catalogue are the Five Songs where Honeybourne turns accompanist for tenor Gordon Pullin. Pullin has been a long time advocate and performer of Baines so the sincerity of these performances is never in doubt. Unfortunately the voice itself is now thin and worn-sounding. The texts – drawn from a wide variety of authors from Elroy Flecker to Rossetti and Tagore – are clear and well articulated but too often it sounds as if the singer is simply having to husband his vocal resources rather than sing the songs as they should be sung. Certainly, I am glad to have had the opportunity to hear these for all the performing limitations. Again there is a sense that Baines the song writer is not as confident yet in this idiom as he is for keyboard alone but the promise is significant. The disc is completed by Robin Walker’s At the grave of William Baines. Walker also acts as the disc’s producer and he contributes a personal note outlining his lifelong engagement with the composer and his music. At 16:06 rather dwarves any of Baines’ music given here – apart from 10:32 for Paradise Gardens the next longest work is the 5:04 The Island of the Fay. The work is not a pastiche of the other’s work but more a response to his life and work and an interpretation of that response. This is a sombre, austere and more overtly modernistic work. Honeybourne gives another predictably assured and convincing performance. Powerful though this piece undoubtedly is, to be honest in the context of this disc I would rather have heard another fifteen minutes of unknown Baines – others may enjoy Walker’s contrasting commentary more than I.

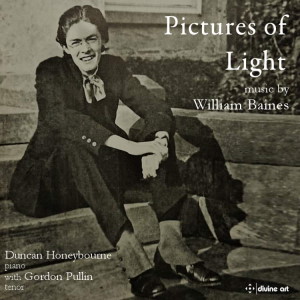

The presentation of the disc is good with the booklet illustrated with some of Richard Bell’s line drawings of locations that inspired Baines as well as biographical and musical information. The recording is pretty good technically. The instrument Honeybourne plays is unnamed and to my ear it is slightly clangourous in the upper register. This sounds like a function of the actual piano itself rather than the acoustic – it is not serious but enough to detract somewhat from the overall listening pleasure. I had not seen the photograph of Baines that is on the booklet cover – it’s a wonderfully natural and relaxed image of a young man grinning at the camera – far more informal than most composer portraits you encounter from 1921. In some way this encapsulates the original and free-spirited nature of both the man and the music he wrote. Hopefully more of his impressive musical legacy will become available soon.

Nick Barnard

Previous review: John France (November 2022)

To gain a 10% discount, use the link below & the code musicweb10