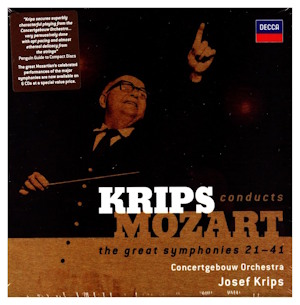

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

The Great Symphonies 21-41

Concertgebouw Orchestra/Josef Krips

rec. 1972-73. ADD

Decca 475 8473 [6 CDs: 385]

All the recordings here had been previously issued separately, first as LPs then as CDs on the Philips label, before Decca brought them together in 2007 in this six-CD box set. They were all recorded between June 1972 and September 1973 – probably in the Concertgebouw, although that is not specified – only a year before the death of the renowned Mozart conductor Josef Krips. He re-opened the Salzburg Festival in 1946 with Don Giovanni, and his 1955 stereo, studio recording remains my top recommendation, even after seventy years as I write – no wonder he nails the ghostly, imposing atmosphere of the opening of No. 39; its mood is akin to so much of the music in the opera.

It is quite likely that the average listener will be familiar only with the later, named symphonies or those such as No. 25, made famous by the film Amadeus – but many of those in the 20s and 30s are absolutely charming ear-ticklers, bursting with invention and there is no one better than Krips to provide an introduction to them. He is in no sense a fusty traditionalist, in that he elicits playing of great lightness, delicacy and detail from the Concertgebouw Orchestra even though they obviously produce what we would now call a “Big Band” sound, somewhat removed from the “period” affect. Instead of using his vast experience as a Mozartian to impart gravitas to the music, Krips is all sparkle and swagger. Perhaps one reason for the neglect of the earlier symphonies here, written by Mozart while he was still in his teens, is that they are mostly relatively short and some are only three or even two movements – or in the case of No. 23, only one ten-minute movement; in a concert, several would need to be programmed together or serve almost as an overture to the main event. Nos. 25 and 29 are acknowledged masterpieces, however, and Krips provides my favourite recorded versions here. Those from No. 30 onwards are mostly four-movement and decidedly weightier in character, although the first well-known named symphony, the ‘Paris’ has in fact only three – but the simpler replacement Andante Mozart wrote for that symphony is included as a bonus.

Despite the classic status of these recordings, I have read criticism of the minuets being somewhat square, tempi too slow, a lack of transparency, and of elements of the last three miraculous symphonies – all written in rapid succession in the summer of 1788 – being “sluggish” etc. These kind of comments fail to acknowledge that these performances were recorded before period notions had taken hold and are as such “traditional”, but there is in them also a kind of prejudiced failure of the ears to hear just how elegant and stylish Krips is in this music; besides, fast does not always equal exciting or interesting; sometimes it just means…well, fast – and Krips likes to give the score space to breathe; I do not find the minuets to be lethargic – just spacious. In any case, for me that last trio of symphonies is a triumph of musicality – although oddly enough, I agree that the first movement of the ‘Jupiter’ is just a tad too urbane and could do with a little more attack. I say “oddly” because the set as a whole is so energised – but that is a negligible flaw in such a superb collection and the drive and precision of multi-themed fugato of the last movement of the ‘Jupiter’ with its astonishing sequence of key changes more than makes up for any slight failings. The first movement of K.550, too, is rather stately but so beautifully and affectionately phrased.

Extensive and very helpful notes by Alfred Beaujean set the musical and historical contexts and provide a guide. The sound is absolutely first-rate, beautifully remastered to the extent that it could almost pass for warm digital at its best.

Ralph Moore

Availability: amazon.com