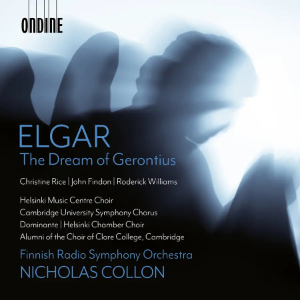

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

The Dream of Gerontius, Op 38 (1900)

Christine Rice (mezzo-soprano – The Angel), John Findon (tenor – Gerontius), Roderick Williams (baritone – The Priest/The Angel of the Agony)

Helsinki Music Centre Choir, Cambridge University Symphony Chorus, Dominante, Helsinki Chamber Choir, Alumni of the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge

Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Nicholas Collon

rec. live, 5 April 2024, Helsinki Music Centre, Finland

English text included

Ondine ODE1451-2D [2 CDs: 91]

Many of the modern audio recordings of Elgar’s masterpiece that I considered in my survey, last updated in 2020, were made under studio conditions (though there are several archive concert performances, including a number conducted by Sir John Barbirolli). Among the recent live audio recordings are those conducted by Sir Colin Davis in Dresden (review) and the Berlin version conducted by Daniel Barenboim (review). The present performance was recorded at a single performance in Helsinki in April 2024. (Perhaps the recording includes a bit of patching from rehearsals; that wouldn’t be unusual in live recordings. If that’s the case, there’s no audible sign of it.) A combined Anglo-Finnish choir was involved together with a team of British soloists, all under the direction of another British musician, Nicholas Collon, who has been the Chief Conductor of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra (FRSO) since the 2021/22 season.

I think it will be easiest if I consider each of the various elements of this performance in turn, starting with the orchestra. Actually, I can be fairly brief because the contribution of the FRSO is consistently superb. The Prelude to Part I inspires confidence right from the start. I suspect that Nicholas Collon’s initial pace may be slightly below the metronome mark of crotchet = 60; if so, it scarcely matters. What does matter is that the Prelude is completely convincing. The orchestral playing is sensitive and refined, though when climaxes arise there’s ample power. In addition, Collon’s shaping of the music is excellent. Following in my vocal score, I noted scrupulous attention to the dynamics; that’s something which always makes a huge difference in Elgar’s music. I’m glad to say that this excellent account of the Prelude is a harbinger of what is to come; the orchestra is marvellously responsive in every respect throughout – in the Prelude to Part II, for example, the strings are truly refined and follow the dynamic markings all the way down to pppp.

The chorus features a number of choirs from England and Finland. Newman’s words are articulated expertly; the diction of the combined choirs is crystal clear throughout. The sound that the chorus makes is well focussed and both fresh and firm of tone. They are very precise and accurate in their rhythmic articulation. The semi-chorus is ideally focused and sings clearly, though their contributions have that ethereal quality that one wants. There are two acid tests for a Gerontius chorus. One is the Demons’ Chorus. Here, there’s power, commitment and precision and the rhythms are sharp. My only reservation about the way that this chorus is sung – especially in the section beginning at ‘Dispossessed, Aside thrust’ – is that I’d like to hear more snarl and bite with deliberately harsh vowel sounds; these are nasty demons, after all (remember Barbirolli’s old quip about bank clerks on a Sunday outing?). However, that’s not to detract from the singers’ achievement in conveying the drama of the Demons’ Chorus. The chorus passes the second acid test – ‘Praise to the Holiest’- with flying colours. The build-up is marvellous; the Angelicals make a fresh, pure sound and every strand of Elgar’s multi-layered choral writing is clearly heard. The great outburst itself at ‘Praise to the Holiest’ is thrilling – the choir has all the impact one could desire. The passage that follows, which can seem like an anticlimax if not accurately sung and conducted, is very well done – here, the scrupulous attention to detail, especially in the matter of dynamics, is a decided asset. After the second acclamation of ‘Praise to the Holiest’, the double-choir section is taken very swiftly by Collon – as it should be – and he really steps on the gas at the accel molto; his choir is unfazed and really delivers the goods. Elsewhere in the oratorio I fond the choral contributions were just as praiseworthy; no one investing in this set will be at all disappointed by the chorus.

What, then, of the soloists? Roderick Williams sings the roles of the Priest and the Angel of the Agony. It has often been remarked that these roles require different types of voices, though only once has this been done in a recording: the 1945 Malcolm Sargent recording used Dennis Noble, a baritone, and Norman Walker, a bass. But, of course, the use of two singers is an extravagance. In my experience, only one or two singers on disc have been equally adept at both roles: John Shirley-Quirk, a baritone – especially on the Britten recording – and Robert Lloyd (bass), who sang on Boult’s EMI recording. I’m not quite convinced that Roderick Williams matches them. He’s a convincing Priest but I don’t feel he has quite the vocal heft to command the stage as the Angel of the Agony; after all, he’s a baritone, not a bass-baritone or bass. Interestingly, when I made one or two comparisons, I found that the opposite was true with Bryn Terfel on the Mark Elder recording. Revisiting that version, I now find him not quite so impressive as the Priest as when I reviewed the set in 2006. Terfel sings very well but I prefer Williams. On the other hand, Terfel’s voice and demeanour seem better suited to the Angel of the Agony. That said, Williams still offers much in that latter role and anyone who knows his voice won’t be surprised to learn that he comes into his own in that magnificent phrase which begins ‘Hasten, Lord, their hour’. Were I cast away on the mythical desert island, though, I’d want to hear the imposing Robert Lloyd in both roles. It helps that he’s a true bass – but with a fine top register – and he brings real presence to both roles as well as fine expression.

Christine Rice is cast as the Angel. I like a lot of what she does. Technically, she’s excellent; the notes at the top of her range are produced very well indeed, though I have the sense, perhaps wrongly, that she has to work a little harder to project the lowest notes in the part. I’m delighted to find that there’s no evidence of vibrato clouding her diction; the text is projected as clearly as a bell throughout. And the words obviously matter to her; she sings with poise and sincerity and offers no little reassurance to the Soul of Gerontius. She has a way of occasionally leaning very slightly on a word for emphasis, usually when a tenuto is marked; I rather like that, especially as the effect is not overdone. One such instance is on the word ‘expressive’ during the passage ‘A presage falls upon thee’. I like her delivery of that solo. Alice Coote, who sings on the Elder recording is also convincing hereabouts. Dame Sarah Connolly who was Sir Andrew Davis’s Angel (review) has a richer timbre than either of these peers and that’s a great help to her in investing the music with warmth. A little later, at ‘There was a mortal’ Ms Rice again demonstrates significant identification with the text – note how she slightly emphasises ‘such that the Master’s very wounds’. Alice Coote is also very committed but, for me, it’s Dame Sarah who, here and elsewhere, draws the listener in to the greatest extent. As the work draws to its gently radiant close, Christine Rice invests the Farewell with a good degree of expression and no little warmth. For me, Sarah Connolly and the unforgettable Janet Baker still reign supreme as the Angel on disc but I enjoyed Christine Rice’s performance and found much to admire in it.

The title role is sung by John Findon. I read on the website of the Cambridge University Centre for Music Performance that he was a late replacement for an indisposed Allan Clayton; I hope there’ll be another opportunity for Clayton to record the role before long. I don’t know how much prior notice Findon had of this engagement. He has a strong, clear voice and I appreciated very much the clarity of his diction. He has the vocal heft for such big moments as ‘Sanctus fortis’ and ‘Take me away’ and he demonstrates sensitivity in the dialogue with the Angel near the start of Part II. However, his interpretation of the role seems rather generalised. His opening is well done: ‘Jesu, Maria – I am near to death’ is suitably fragile. A little later, though, I miss a sense of awe at ‘’Tis this strange innermost abandonment’. As I said, he has the heft for ‘Sanctus fortis’ but within that taxing solo I don’t detect a sufficient variety of expression – for instance, he doesn’t get much terror into his voice at the nightmarish passages that begins ‘And, crueller still, A fierce and restless fright…’. On the other hand, ‘Novissima hora est’ is well done; Findon sounds exhausted and humble. In Part II, he brings a lighter voice to the dialogue with the Angel and I like the sense of wonder he imparts at ‘How still it is’. ‘Take me away’ starts thrillingly and Findon uses dynamics and vocal expression to give a good account of this solo. Unfortunately, comparisons are not kind. If we go back to the very first solo, ‘Jesu, Maria – I am near to death’ is well interpreted by Findon. Paul Groves, who sings for Sir Mark Elder (review) makes rather more of the words and music, I think. But Nicky Spence, on the most recent recording, conducted by Paul McCreesh (review) offers even more than either of them. Spence is infinitely more expressive, conveying a genuine sense of fear. I think that in the whole of ‘Sanctus fortis’ he puts more light and shade into his singing than Findon manages. When we get to ‘Novissima hora est’, Spence spins the line on a thin thread of tone; it’s very moving. I’ve only mentioned comparisons from Part I but I made several more from Part II which similarly show Findon to be too generalised in his approach by comparison with Spence in particular. It’s important to recognise that both Spence and, I believe, Groves made their recordings under studio conditions, whereas Findon’s performance is a one-off live account but even with that caveat I don’t think his performance is on the same level as that of Spence in particular; Spence’s interpretation is far more nuanced. I hasten to say that had I attended the performance in Helsinki I’m sure I’d have gone home feeling satisfied but when it comes to the repeated scrutiny of a recording, this isn’t an assumption of the title role that moves the needle.

I was impressed with the conducting of Nicholas Collon. There were one or two instances where I thought that perhaps his tempo selection was a little on the swift side. For the most part, though, I thought his pacing of the score was judicious and idiomatic. The conducting displays fine attention to detail and much empathy with Elgar’s music. He conveys the drama very successfully but he’s equally good in the more intimate passages.

The recorded sound is excellent – I prefer it to the sound on the Hallé recording conducted by Elder, which doesn’t have the same degree of impact; the Signum recording for McCreesh, though, is very fine. Ondine’s engineering team have balanced everything very skilfully and the fine dynamic range does full justice to the musicians’ efforts in that regard.

There’s much to admire in this performance of The Dream of Gerontius, especially the choral singing and the orchestral playing, but in the last analysis I don’t believe that it challenges the existing leading recommendations.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free