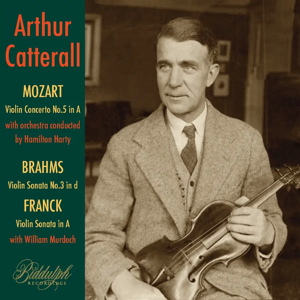

Arthur Catterall (violin)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Violin Concerto No.5 in A, K.219 (1775)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Violin Sonata No.3 in D minor, Op.108 (1888)

César Franck (1822-1890)

Violin Sonata in A (1886)

Orchestra/Hamilton Harty

William Murdoch (piano)

rec. 1923-24, Columbia Studios, London

Biddulph 85057-2 [75]

Arthur Catterall (1883-1943) was one of Britain’s most eminent violinists, born in the decade that produced Albert Sammons, Marie Hall and May Harrison and many other notables. He is principally remembered for his leadership of the Hallé and BBC Symphony orchestras, under Hamilton Harty and Adrian Boult respectively, but he was also a distinguished soloist with a flair for the Slavic repertoire – for Tchaikovsky and Sibelius as well as Dvořák – and for taking on premieres, such as Moeran’s Concerto, which was dedicated to him, and of course for his career in the recording studios. He had a much-admired string quartet, but he also recorded as soloist for Columbia in the twilight years of the acoustic system. Three of these recordings have now been reissued by Biddulph.

All these recordings have been reissued in some way before. The Brahms has been reissued on Historic Recordings as has the Franck. The Mozart Concerto has been reissued more recently by Pristine Audio in a disc devoted to Hamilton Harty’s accompanying duties that also included Catterall’s recording of the Bach ‘Double’ with John S. Bridge. As I reviewed them in their previous guises, I’ll reprise much of what I wrote here, suitably modified for this review.

“The Brahms sonata was the first ever recording of the work. Catterall often performed the Concerto and Double Concerto (with Suggia and with Lauri Kennedy), but neither was recorded. Sammons is on record as having admired this recording of the sonata — given that his sonata partner William Murdoch is playing here too, that might seem only too obvious — but it is indeed a fine, noble, and intelligently conceived performance and the approach to the climax of the slow movement is especially convincing. The only way you’d be able to gauge where the side-joins are is by slightly increased surface noise, or by the de-accelerandos made to prepare for the turn-over.

The first ever complete recording of the Franck sonata had a weird history. It was never issued in Britain and when it was issued in North America there was a mix-up, a 3-disc album appearing with three movements wrongly ordered and missing a complete movement, before it was replaced by the complete four-disc set, the error having been spotted pretty quickly. The acoustic Thibaud-Cortot recording was issued at around the same time, a traversal that has become eclipsed by their subsequent electric remake. Catterall was more a classicist than an overtly romantic player and some of his devices make him sound rather old-fashioned – his propensity for extensive portamentos including downward ones, for instance. His tone was quite slim, not at all opulent, finely equalized across the scale and his trill is not of electric velocity. He had an on-the-string lyric quality, and a way of phrasing that is intensely attractive. The Franck has opening paragraphs that offer examples of his fluid, portamento-motored phraseology, somewhat excessive in places because so proximate. Lyric intensity and a degree of ‘innocence’ inform the playing. Murdoch is equally splendid in a work where the pianist bears more than his fair share of technical difficulty.

Interestingly – I didn’t notice this on the 78 – one hears an acoustic change on the second side of the second movement, where the violin is suddenly more prominent and the piano a touch more splintery. Maybe Catterall moved fractionally closer to the recording horn for that matrix. There are some thumps at this point in the transfer.

Catterall’s recording of Mozart’s A major Concerto on 10 April 1924 was the work’s premiere recording, though Parlophone in Germany had somewhat earlier released a version without the slow movement with a violinist called Hedwig Fassbänder. If Harty’s 1933 recording of the Sinfonia concertante with Sammons and Tertis was his most celebrated recording of a Mozart concerto, this is probably his least remembered. Catterall plays in that familiar on-the-string style of his laced, in his introductory passages, with lashings of portamenti. The bass reinforcements are relatively discreet in the outer movements but more obvious in the slow movement.

It was perfectly acceptable to slow down for a side change but when one listens today ‘joined up’, these moments sound – inevitably – less than musical and there’s nothing to be done about it. Listen to the rallentando at 4:04 in the first movement for example or the rather more musical one at 7:38. These are inevitable corollaries of the recording process at the time, gently to ease the music to the end of a side. There’s a six-bar cut towards the end of the slow movement and a small snip in the finale. Catterall’s slides are very audible again and so is his crystalline tone production. No wonder Toscanini so admired Catterall when the Englishman was leading the BBC Symphony. A final point: a surprising amount of inner part orchestral detail can be heard.”

The transfers come courtesy of Bryan Bishop. The Brahms is much better than the Historic Recordings transfers, having no clicks and first-class side-joins. The Franck is about the same. I tend to prefer Mark Obert-Thorn’s Pristine Audio transfer of the Mozart as Bishop’s transfer has preserved some blemishes on one side and the side-joins are not quite as seamless as Obert-Thorn’s.

The booklet is most attractively produced with a particularly sympathetic cover photograph of the violinist and an eight-page biography of Catterall by the present writer. His late acoustic Columbia recordings, made when Sammons had defected to record for Vocalion, allowed him to record important elements of his repertoire. This disc is a notable if specialist salute to an admirable musician who has been unjustly overlooked for too long.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.