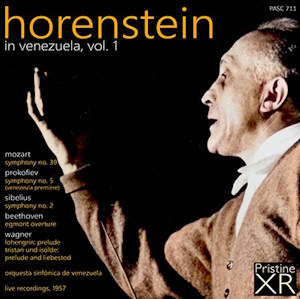

Jascha Horenstein (conductor)

Horenstein in Venezuela Volume 1

Orquesta Sinfónica de Venezuela

rec. live, 25 January and 1 February, 1957, Caracas, Venezuela

Pristine Audio PASC711 [2 CDs: 149]

I’ve heard – and in many cases reviewed – a good number of live recordings of music conducted by Jascha Horenstein, but this disc, the first in a projected series is rather different. To the best of my recollection, every time I’ve previously heard Horenstein he’s been at the helm of a European orchestra, such as the Berlin Philharmonic or the London Symphony. With these recordings we find him on the other side of the Atlantic, in Venezuela, leading the Orquesta Sinfónica de Venezuela (OSV).

As Misha Horenstein relates in his notes, Horenstein paid three visits to Caracas to conduct the OSV, in 1954, 1955 and 1957. He goes on to tell us that “Venezuela was Horenstein’s eighth Latin American country after having toured the region extensively, and with great success, from the mid-1940s on.” As Misha Horenstein explains, these Latin American engagements were mainly in Mexico and Argentina but, sadly, recordings exist only of concerts that he gave in Venezuela and Uruguay. It seems that Horenstein was not prepared to travel such a long distance and simply conduct standard repertoire; he also sought to stimulate his Latin American audiences by exposing them to music that might well be new to them. Misha Horenstein tells us that the repertoire during the visits “included the Venezuelan premieres of Mahler’s First Symphony, Bruckner’s Third, Mahler’s Fourth, Prokofiev’s Fifth, Strauss’s Metamorphosen and Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht. Four of these premieres occurred during a single two-week period in February 1957!” The Prokofiev work is included here; I hope we’re going to hear at least some of the other Venezuelan premieres in future instalments.

At the time of Horenstein’s engagements with them, the OSV was quite a young ensemble; I believe it was founded in 1930. Misha Horenstein is admirably frank about the quality of the orchestra in the mid-1950s. He writes as follows: “One might justifiably ask what possible value or interest could there be in a series of rather average recordings with a third-tier orchestra lacking the refinements of sound and execution expected by today’s listeners, in works of now standard repertoire that are available in dozens of better sounding, better played versions, including some conducted by Horenstein himself?”. He goes on to answer his own question asserting that “[Jascha Horenstein’s] views of all these works, especially when captured live as here, remain engaging and highly absorbing no matter when or with whom he performed them, while his ability to inspire an orchestra he did not know well to cooperate with one mind and one heart, sometimes in music they did not know at all, is awe inspiring.” I hope that my comments about these recordings will, to some extent, furnish additional answers to those very fair questions.

Two concerts from Horenstein’s last trip to Venezuela are represented here. The Sibelius and Wagner pieces were all performed at 25 January 1957. Pristine present the pieces in the same order in which they were performed on that occasion: I gather that the concert concluded with one more Wagner piece, the Overture to Die Meistersinger but there wasn’t space on the discs to include that. The start of the Sibelius symphony may raise an eyebrow or two – it did with me – on account of the rather deliberate tempo. That said, I found that I adjusted quite quickly and came to admire a reading that is darkly powerful. Not every aspect of the OSV’s playing is precise but I think there’s little doubt that they knew what their conductor wanted and did their utmost to execute his vision. There are some issues with tuning in the slow movement but those don’t detract from the conviction of the performance. I suspect that quite a lot of rehearsal tine was devoted to the Vivacissimo, and especially to the rapid string figurations; if so, it was time well spent because the strings deliver the goods, even though Horenstein – rightly – makes no concessions in terms of tempo. Again, it has to be said that intonation is somewhat fallible in the slower sections of this movement. The transition to the finale is a bit scrappy but once that movement gets underway, I think the words ‘heart and soul’ would fairly describe the OSV’s performance. I found myself caught up in the music. Horenstein brings the symphony to a majestic conclusion and even if the intonation is less than perfect among the brass section, the performance as a whole justified the enthusiastic applause.

At this stage, let me give an interim judgement on the playing of the OSV, based on the Sibelius performance. I think the string section is the strongest one; they play pretty well for Horenstein. On the whole, the woodwind section makes a decent showing – though we can hear some intonation issues, there are some well-delivered solos to admire. The Achilles heel is the brass section, including the horns. A number of errors, mainly cracked notes, are apparent and there’s also a tendency to let their enthusiasm get the better of them in loud passages. It’s only fair, though, to balance criticism with praise for the commitment with which the entire orchestra plays.

The two Wagner items are well done. I was particularly pleased by the sensitivity with which the strings play the opening minutes of the Lohengrin prelude. I suspect that playing these Wagner pieces in the way that Horenstein wanted stretched the players but they respond very positively. Incidentally, the Lohengrin prelude is unique in this collection in being preserved in stereo.

A few days later Horenstein and the OSV were back onstage for a concert of music by Beethoven, Mozart and Prokofiev played, I presume, in the same order as on the disc. The opening chord of the Egmont overture is rather strident but thereafter the performance settles down and we hear a good account of the music. My only real criticism is that the trumpets tend to be too dominant; that’s especially true in the presto conclusion. The source material for the Mozart symphony was not quite complete; the very beginning of the first movement was missing and Pristine have spliced in the bars in question from another Horenstein recording. The patching is seamless; to adapt Morecambe and Wise’s famous phrase, I couldn’t hear the join. I liked this performance. There’s good tension in the Introduction while the main allegro is spirited. In the slow movement, I especially admired the delicacy of the string playing in the first two or three minutes; indeed, the movement as a whole is a success. It’s clear that not all the rehearsal time had been spent on the Prokofiev symphony. The Minuet is sturdy, with a nicely turned trio, while the finale is spruce and energetic.

The performance of Prokofiev’s Fifth represented the symphony’s Venezuelan premiere. When I received this set, I thought it was pretty enterprising to play the work in February 1957, bearing in mind that the work’s first performance had been given only in January 1945. But my admiration for the enterprise of Horenstein and the OSV was heightened when I learned quite recently that the august Berlin Philharmonic played the work for the first time just over two weeks after this Venezuelan premiere. In passing, I wonder how much music by Prokofiev the OSV had played prior to their encounter with this symphony.

It has to be said that in this performance not all internal balances are satisfactorily rendered; one can be sympathetic to that. The fallibility of the brass is a factor at times and, indeed, the OSV as a whole was clearly challenged by the symphony. However, there’s also much on the credit side of the ledger. As I listened to the first movement, I appreciated Horenstein’s grip on the music and it seemed to me that the members of the OSV convey the spirit of the piece; they’re highly committed. It has to be said that, despite Andrew Rose’s best efforts, the recorded sound is under strain at the climaxes. At the start of the second movement Horenstein takes no prisoners with his tempo selection but the strings and woodwind respond with deft playing. This is a movement which requires precision from start to finish; the OSV do a very good job. There are some horribly exposed, high-lying lines in the slow movement, especially for the violins. While the playing isn’t flawless it’s very creditable. Overall, this is a convincing performance. That’s true also of the finale; I found I could listen past the fallibilities in the playing. It was heartening to hear the audience give the performance – and, I hope, the music – a resounding reception at the end.

I don’t think that anything I heard in the Wagner performances or in the second concert altered the interim verdict I reached on the OSV after their Sibelius performance. Misha Horenstein’s reference to a “third-tier” orchestra is reasonable, but I can’t fault their commitment. I gather that during his 1957 visit Horenstein had no fewer than fifteen rehearsals. I bet they were intense, but on this evidence the time was well spent. And without wishing to sound patronising – which is certainly not my intention – engaging a distinguished and exacting conductor who brought challenging programmes with him can only have raised both standards and horizons in this relatively young orchestra. These performances also demonstrate Jascha Horenstein’s capabilities as a conductor, I think. It’s one thing to get excellent performances out of orchestras of the calibre of the LSO and the Berlin Philharmonic; it’s quite another to take a lower ranked orchestra like the OSV, get them to raise their game and teach them scores such as the Prokofiev Fifth.

The source material for these recordings has its limitations but Andrew Rose has transferred them skilfully; no one accustomed to listening to historic recordings will find that the sound hampers appreciation of the music-making. I hope to review a further instalment in this series, containing a third programme from 1957 and once from 1954 very soon. This is, inevitably, a specialist release but admirers of this great conductor will want to hear this intriguing example of him working, as it were, off the beaten track.

John Quinn

Availability: Pristine ClassicalContents

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op 43

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Lohengrin. Prelude to Act 1

Tristan und Isolde – Prelude and Liebestod

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Overture Egmont, Op. 84

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, K.543

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, Op. 100