Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Ein deutsches Requiem

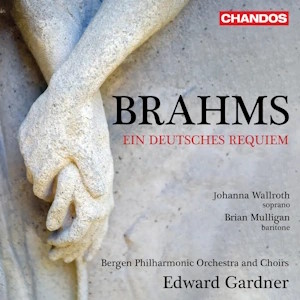

Johanna Wallroth (soprano); Brian Mulligan (baritone)

Edvard Grieg Kor, Choir of Collegium Musicum

Bergen Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra/Edward Gardner

rec. 2024, Grieghallen, Bergen, Norway

German text and English translation

Chandos CHSA5271 SACD [68]

The Brahms’ Requiem had something of a mixed reception and has since had a chequered recording history. It is a work most famously excoriated by George Bernard Shaw’s witticism that it ”could only have come from the establishment of a first-class undertaker…patiently borne only by the corpse.” Notwithstanding Shaw’s lampooning, Karajan, for example, clearly loved it and regularly recorded it over his career; there are studio accounts from 1947, 1964, 1976 and 1983, usually with excellent soloists but some engineering and balance issues, failings of placement and intonation with the Wiener Singverein – whom he invariably employed – and a solemn affect which has led many critics to be derogatory about them all. Yet the buying public loves both the work and those recordings; Colin Clarke in his 2007 review calls the 1947 recording “a supreme achievement”. I personally certainly enjoy Karajan’s last version above all, but also love the contributions of soloists Gundula Janowitz and Eberhard Waechter in the 1964 outing (review). Nonetheless, I concede that there have probably been more hits than misses in its recording history. I have settled on a few more, especially André Previn’s 1986 recording on Teldec with the RPO, the Ambrosian Chorus and two superb soloists in Margaret Price and Samuel Ramey, also Lorin Maazel in 1976 on Sony with the forces of the new Philharmonia, Ileana Cotrubas and Hermann Prey, and Klaus Tennstedt with Jessye Norman and Jorma Hynninen.

All of which serves only as a pre-amble to an assessment of this new Chandos Issue. The first thing to note is that Gardner’s tempi are swift; most ‘Old School’ conductors like Karajan, Kempe, Solti and Furtwängler take around ten minutes more over the work – yet Klemperer – surely as ‘Old School’ as you can get – in his classic recording, takes under seventy minutes and in a dynamic live recording from 1956 on the ica label (review) he is even faster at a breathless, driven 63 minutes. Most more modern exponents join Gardner here with faster accounts well under seventy minutes; back in 2012 I reviewed a live performance from Kurt Masur which clocked in at an hour. Certainly the trend in performance of classical music in general over the last fifty years has been to speed up. As ever, speed isn’t everything but it’s often an index to an interpretative stance and I guess conductors are eager to avoid coming over as “too traditional” and stuffy.

Brahm’s own text – a compilation of slightly adapted extracts from his Luther Bible – is, after all, heavily geared towards comfort and consolation for the bereaved rather than petitioning for the salvation of the departed, so a less “monumental”, more “human” – to borrow the composer’s own term – approach is surely justified. Playing the first movement of Karajan’s last recording immediately after a first listening to this new one drove home to me how much grander and more numinous is that older recording compared with the crisper, more immediate Bergen forces. Having said that, Gardner skilfully gauges the build-up to the final, climactic “getröstet werden” such that it loses no impact. In the solemn funeral march of the second movement, however, I am underwhelmed and much prefer the slower, statelier grandeur of Previn’s account. This difference between the two approaches is consistent throughout and perhaps my taste has too long been formed and fixed by exposure to older recordings, but I find Gardner’s demeanour simply too low key and I do not experience the scalp-prickling thrill at the reprise of “Denn alles Fleisch” that Previn and Karajan arouse. Nor is there as much contrast between the two stern outer and quiet inner sections of that movement – though Gardner’s combined choirs sing “So seid nun geduldig” (Be patient, therefore) beautifully, in tune and with great compassion, and the lilting “How lovely are thy tabernacles” goes swimmingly.

For me, however, the central point of the whole work is that triumphant proclamation of faith in the choral outburst, “Aber des Herrn Wort bleibet in Ewigkeit” (But the word of the Lord endureth for ever); it is my litmus test whereby the success of any performance stands or falls – and Gardner’s delivery is…just nice but conveys none of the sheer impact generated by the choral forces and blaring brass of Karajan – who is the only conductor to get this absolutely right in all three of his recordings – and with Gardner, key words like “Schmerz und Seufzen wird weg” (Grief and sighing shall flee away) are insufficiently punched out, so the potential for real drama is inadequately realised. (Maazel is somewhat lacking here, too, in an otherwise fine recording.)

We then come to the role of the soloists. Sturdy baritone Brian Mulligan sings nobly with beautiful German diction but a little habit of sliding up to some strained high notes is irritating and the competition is tough. He hasn’t the massive presence of Hotter or the warm humanity and beauty of tone of Waechter, who is given much more time and space by Karajan to make his points. The same is true of José van Dam, who is mesmerising in his prime, and bass-baritone Sam Ramey for Previn finds a patriarchal gravitas which is equally absorbing. Johanna Wallroth is similarly up against the best in Gundula Janowitz, Margaret Price, Ileana Cotrubas, Jessye Norman and Barbara Hendricks, and her slightly warbling vocal production militates against her measuring up to the soaring, silver purity of her predecessors. She’s not bad, but…

The final two movements are sprightly and confident; co-ordination is excellent with excellent balances among the choral sections and orchestra; “Herr, du bist wurdig” goes with a real lift and spring, even if again I could do with a little more weight. I sometimes find that with some performances the finale emerges as a tad anticlimactic – but perhaps the fault there is Brahms’, not the performers – and here the choir spins a seamless line on the repeated “von nun an” (“henceforth” – or maybe better, “from now on”), creating a commendably angelic aura of sound.

The engineering is, as ever with Chandos, first class. In the end, this is a fine but not outstanding account which fails to shift my loyalty away from more sumptuous and stirring recordings.

Ralph Moore

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free