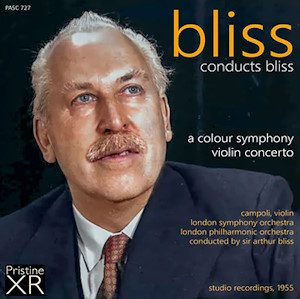

Bliss conducts Bliss

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975)

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, F. 111(1955)

A Colour Symphony, F. 106 (1921-22, rev. 1932)*

Alfredo Campoli (violin)

London Philharmonic Orchestra / *London Symphony Orchestra /Sir Arthur Bliss

rec. 9-11 November 1955, *23-25 November 1955, Kingsway Hall, London

Pristine Audio PASC 727 [69]

The fiftieth anniversary of the death of Sir Arthur Bliss falls in 2025; I hope there’ll be a number of recordings and performances of his music. Pristine is out of the blocks early with a release of these two mono recordings which Decca made in 1955; the recordings have been refurbished in Pristine’s Ambient Stereo.

The Violin Concerto was commissioned by the BBC in 1953. It was written for and dedicated to Alfredo Campoli who, I believe, was closely consulted by Bliss on the design of the solo part. The work is on a big scale; here, it plays for 37:46. Pristine reproduce some comments made by Lionel Salter when he reviewed the Decca disc for Gramophone in 1956. His generally very positive view of the work included the following observation: “Is it, perhaps, a little long for its material in the first movement?” I think that’s a perceptive comment. In this performance, the movement lasts for 14:36. Actually, it’s quite well-balanced against the finale (16:31) but I think Salter had a point. In the first movement, Bliss gives his soloist abundant opportunities for display, which Campoli seizes upon with relish. But there are also more lyrical passages where Bliss’s romantic vein is to the fore; in these Campoli’s cantabile capabilities are a decided asset. One such episode starts at 4:37 where Campoli’s pure, singing tone is ideal for the music. Even more beguiling is the quiet episode beginning at 9:49 where the combination of a sweet, song-like violin and delicate accompaniment produces a delectable effect.

The central second movement is, effectively, a scherzo, even though it’s not formally designated as such. Here, the music fairly scampers along; Campoli treats us to point-of-a-needle playing and the LPO is similarly dexterous. I have in my collection a disc on the long-defunct BBC Radio Classics label which includes a live performance which Campoli and Bliss gave in December 1968, this time with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The author of the booklet notes, John Mayhew, states that Bliss sanctioned an optional two-minute cut in this movement and that the cut in question was observed in 1968. Since the timings for the two recordings differ only by some twenty seconds, I infer that the cut was also made in the 1955 commercial recording. (Mayhew also mentions another optional cut, this time involving an orchestral passage in the finale; in this case, without access to a score, I can’t be as confident that the cut was made in 1955; the commercial recording comes in at 16:31, the 1968 broadcast at 15:36.) The concerto’s finale opens with an extended Introduction, marked Andante sostenuto. Hereabouts, Bliss’s penchant for warm, romantic writing is much in evidence; I greatly enjoyed the beautiful, rhapsodic playing which Campoli offers here. The main body of the movement (Allegro deciso in modo zingaro) begins at 5:07. The music that follows is spirited, as is the performance. Campoli is technically commanding in the extended cadenza (to which the orchestra makes some contributions) before the short, emphatic coda, from 15:25, sees the concerto whirl to an exhilarating conclusion.

This is a distinguished recorded performance of a concerto that remains too little known. The recording was in the hands of producer John Culshaw and engineer Kenneth Wilkinson. As you might expect, they did a fine job. Campoli is forwardly balanced – though by no means excessively so – but while the listener’s ear is, rightly, drawn to his excellent playing, the orchestra is well served by the recording.

A couple of weeks later, Bliss was back in Kingsway Hall to record A Colour Symphony for Decca. He had the same recording team of Culshaw and Wilkinson, but a different orchestra; the London Symphony Orchestra took the place of the London Philharmonic. Andrew Rose says in a note accompanying this release that it is “hard to understand” the switch of orchestras. Of course, it may have been nothing more than a scheduling clash, but there’s a certain rightness about the choice of the LSO for this assignment since it was the 1922 incarnation of that orchestra which gave the first performance of the work.

A Colour Symphony represented an important step forward for Bliss in terms of his profile. It was commissioned for the 1922 Three Choirs Festival, held that year at Gloucester, and Bliss was recommended to the Festival for a commission, along with Howells and Eugene Goossens, by no less a figure than Elgar. Unfortunately, Elgar was lukewarm after the premiere and this caused a rift in their relationship for a few years. Paul Spicer relates in his fine biography of Bliss (review) that the first performance was a fraught affair. Not only was insufficient time allocated for rehearsal but, worse still, just before the performance was due to begin it was discovered that the platform, on which was assembled not only Bliss’s large orchestra but also the Festival Chorus (for other works) was too full. Incredibly, it was decided that the best course of action would be to remove some of the orchestral musicians, no matter how important their parts were! One such casualty was the tuba player. In those days it was the convention that there was no applause after any Three Choirs performance – the taboo was not broken until 1969! So, we can only imagine how A Colour Symphony was perceived by its first audience. My guess is that had applause been permitted it would have been no more than polite.

Nowadays, we can appreciate A Colour Symphony for the very fine work that it is; we can also lament that concert performances are quite rare. Here, it receives a fine performance. Bliss was inspired, I believe, when he came across a book about heraldry and he learned of the symbolism attached to certain colours in heraldry. The first movement, Andante maestoso, is given the title ‘Purple’. Here, the music is characterised by nobility and warm romanticism; there’s an Elgarian air to the movement. As I listened to this performance, it struck me that this is an early example of Bliss’s ability to compose ceremonial music, which later stood him in such good stead when he became Master of the Queen’s Musick. The following movement, ‘Red’ is the work’s scherzo (the marking is Allegro vivace). This is dashing music, here performed with no little panache. This movement offers, I think, a harbinger of Checkmate. In an exciting rendition, I was especially struck by the swagger of the LSO brass section in the closing pages.

The third movement is ‘Blue’ (Gently flowing). This is a fine invention, full of Bliss’s trademark romanticism. Last comes ‘Green’ (Moderato). This has a good deal of fugal writing in it. The strings have the first fugal episode, right at the start and under the composer’s direction the writing seems quite severe. A little later (3:28), it’s the woodwind who have fugal material; their music is almost hyperactive. In the last few minutes, Bliss unleashes the full orchestra with some really exciting writing, including two sets of timpani going hell for leather (6:11): I wonder what the original Three Choirs audience made of that. It’s a splendid conclusion to the symphony and Bliss obtains a terrific response from the LSO; Lionel Salter, reviewing the original Decca release in Gramophone, described the performance of the symphony as “full-blooded” and I wouldn’t disagree.

The recording of A Colour Symphony has been in circulation on more than one previous occasion. I mentioned it in a review of a Dutton set several years ago, though I didn’t cover it in detail; my primary focus was on other works. I still have the set and some A/B comparisons suggest that there’s not a great deal to choose between that transfer and the new Pristine version; both are very good. I think the Dutton transfer offers sound that is a fraction brighter – this benefits the timpani at the end of the symphony – but listeners may prefer the slightly warmer results that Andrew Rose has achieved. Decca’s original recordings were very good indeed and Andrew Rose’s transfers have refreshed them nicely.

Sir Arthur Bliss was a fine conductor of his own music and this compilation allows us to hear excellent recordings of two of his major works in fine transfers. Any Bliss admirer who doesn’t have these performances in their collection should not hesitate.

Previous review: John France (January 2025)

Availability: Pristine Classical