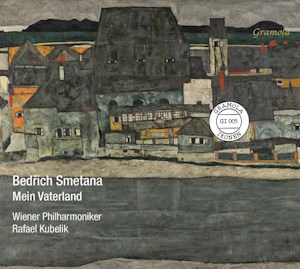

Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884)

Má Vlast

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Rafael Kubelik

rec. 1957, Vienna

Gramola 92005 [74]

Back in the 1960s this was the recording (then on Decca) by which I first made my acquaintance with Smetana’s massive cycle of symphonic poems based on the over-arching theme of his homeland. There were at the time a good many alternative recordings of Vltava, the second and most popular of the series, and a smattering of From Bohemia’s woods and fields, the fourth, but otherwise only one other complete rival which was readily available at the time – a decidedly unidiomatic and dutiful recording under the baton of the very upright and English-sounding Sir Malcolm Sargent. There were also a handful of more ‘authentic’ recordings on Supraphon under veteran Czech conductors such as Vaclav Talich, but they were not readily available even as imports; and even nowadays after remastering their sound cannot be described as conspicuously high in quality. In later days there have been a plethora of rivals – the cycle as a whole is fortunate in that it fits conveniently onto the length of a single CD – but it was interesting to encounter again a recording which I had not heard for many years, thanks to the enterprising reissue programme of Gramola.

However it is unfortunate that the very opening of Vyšehrad, with its elaborate harp cadenzas, launches this cycle – the second of several recordings under the baton of Rafael Kubelik – in such a conspicuously lack-lustre fashion. It is not just that the acoustic of the Sofiensaal, soon to be the basis for Decca’s Wagner Ring, lacks the sense of immediacy demanded by the music, although the harp parts lack the ring and clarity that is really essential here. It is also that the whole sound is rather bass-heavy, obscuring the upper notes of the instruments themselves, and the fact that the concertante harp parts which recur throughout the first of these tone-poems often recede into almost total inaudibility even when their figurations are thematically important. Decca at this time seem still to have been experimenting with the sound of recordings in their Vienna location – they had only started to hold sessions there in 1956 – and the resulting sound is often tubby and lacking in the ring and clarity that they were to capture even a few months later. The violins, and the strings in general, lack warmth in passages which really demand lyrical expression; and the brass too have a bluntness of tone where the heavier instruments – trumpets and trombones – persistently dominate the horns even when they should be balanced with them.

There is another problem, too, and this is more seriously not a matter of the recording but the performance itself. In the late 1950s the Vienna Philharmonic woodwind displayed a tone which could perhaps be kindly described as “characterful” with the oboes in particular adopting a thin nasal sound which could verge on the acidic (listen for example to their delivery in Solti’s Tristan und Isolde recorded in the same venue a year or so later). Here they persistently fail to expand in the upper register, sounding pinched and plaintive even in passages which Smetana has marked dolce and espressivo. That helps the blend with the flutes in the many sections of writing for the woodwind alone, but the price is high, and Smetana’s copious ‘hairpin’ markings to indicate phrasing are too often smoothed out. The clarinets too lack warmth in many of their more lyrical passages. Even more seriously the second bassoon totally fails to appreciate the joke when in Šárka he has to imitate the sound of snoring when the heroine casts her rival warriors into a drunken sleep; Smetana has very precisely asked the player to grunt away in the lowest register fortissimo while the remainder of the woodwind subside into slumber. Here the passage makes almost no effect whatsoever, the player altogether too obviously anxious to avoid making an ugly sound.

This is all part-and-parcel of Kubelik’s approach to the score in which, one should emphasise, was his earliest stereo recording of a work to which he returned persistently in his later career. John Culshaw in his autobiography Putting the record straight, comments on his strenuous efforts to avoid overly dramatic effects in his interpretations, smoothing out contrasts and downplaying discordant elements to achieve a unity of approach and style. Unfortunately this does not work with Smetana in the more overtly dramatic passages of Tábor and Blaník where, even if there is no specific programme, the composer goes to considerable lengths to convey almost operatic portrayals of battle and warfare. The heavy timpani interjections in the latter piece have a thunderously cavernous quality (not always impeccably tuned) that almost obscures their important rhythmic impact. Cymbal crashes, specifically notated by the composer to be allowed to resound, are damped crisply (diminishing the contrast when staccato is requested); and the triangle is recessed to a degree that renders it almost inaudible even when it is clearly intended to add an edge to the already loud sounds that Smetana is conjuring from his orchestra.

Incidentally, listening to this set with score in hand, I noticed one very peculiar effect in the very closing bars of the work. While the whole of the orchestra have a series of sharp chords marked staccatissimo, the triangle is by contrast asked to play a series of rapid semiquavers (like a trill) which are quite precisely notated, not just once but several times. This might be an attempt by the composer to ensure audibility while expecting the trill to be subsumed in the resonance of the hall; but it seems an odd way of going about it, and I suspect that if Smetana’s instruction is observed precisely the effect might be both novel and effective. I cannot recall any conductor attempting to realise the composer’s demands; it would be interesting.

The two best-known movements in the cycle, Vltava and Bohemia’s woods and fields, come off best in Kubelik’s performance; although in the former the notorious passage just before the appearance of the water-nymphs with its awkward writing for low oboes sounds cautious rather than enchanted, and afterwards the high-lying melody in the violins is not as clearly delineated as it should be. Even so, given the dubious qualities of interpretation, playing and recording described in this review, this cannot any longer be regarded as a principal contender for a version of Má Vlast to be included in a collection. There have been so many preferable versions since, not least from Kubelik himself including a famously emotionally engaged live performance in Prague when he returned to Czechoslovakia after the fall of the Iron Curtain some thirty years later.

But I am nonetheless grateful to Gramola for allowing me to hear again a recording which I remember with lingering affection from the days of my youth. And the physical presentation, in a gatefold sleeve with inbound booklet containing notes in English and German, is very handsome, a decided cut above the parsimonious packaging with which international labels all too frequently encumber their period reissues.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free