Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

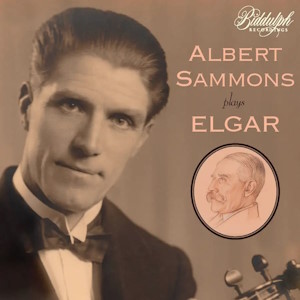

Albert Sammons plays Elgar

Violin Concerto in B minor, Op.61 (1910) – 1916 and 1929 recordings

Violin Sonata in E minor, Op.82 (1919)

New Queen’s Hall Orchestra & unnamed orchestra/Sir Henry Wood

William Murdoch (piano)

rec. March 1916 (Concerto, abridged); March-April 1929 (Concerto); February 1935 (Sonata), London

Biddulph 85054-2 [82]

Albert Sammons’ 1929 recording of the Elgar Concerto has been available in a number of CD transfers made over the last three decades, but it’s instructive to recall that until A.C. Griffith’s LP transfer in the early 1970s it hadn’t been available since its withdrawal in 1946. Up until then you needed the 78rpm set to hear it. This new release couples it with his truncated 1916 recording of the Concerto – abridged to a third of its length – and the 1935 recording of the Violin Sonata made with Sammons’ long-time pianist, William Murdoch.

The two early complete Concerto recordings – Sammons with Wood in 1929 and Menuhin with Elgar in 1932 – are invariably compared and contrasted. The former is thrusting and masculine, the latter more lingering and beautifully indulged. However, there are plenty of indications that when he conducted it for Sammons, Elgar was a much more zestful interpreter of his Concerto, as one would expect from his conducting of the symphonies. Perhaps Nigel Simeone’s forthcoming book about Boult and Elgar will tell us more, as Boult seems to have made timings of his own and Elgar’s conducting of his works. Perhaps he can confirm that Landon Ronald and Sammons took about 45 minutes when they performed it in Liverpool in 1927.

In any case, this is, for me, the great recording of the work though there are many others that will give rich rewards. If you judge works by timings, Sammons takes 43:20, Menuhin just under 50, Campoli 45, and Heifetz – who consulted Sammons on the Concerto just before he recorded it with Sargent in 1949 – took 41:40. While we’re at it, the Italian virtuoso Aldo Ferraresi took exactly Heifetz’s tempo when he recorded it live in 1966 (it’s in a big Rhine Classics box). Even more than tempo though – or at least strongly related to it – are matters of tone, consistency of narrative expression, appropriate vibrato usage, and a cumulative sense of musical argument. In all these matters, Sammons proves unique. Yes, this is a recording from 1929 and I’m not advocating it as your up-to-date choice. Some have always worried about Wood’s bull-at-a-gate conducting (Lady Elgar certainly did) but it provides Sammons with a perfect canvas through which to drive through a Concerto which, in other hands, can splinter into three disparate movements, or meander.

There have been two Pearl transfers, one of which coupled the Concerto and Sonata as here, though not the 1916 version, and both have a rather congealed bass line, an Avid fake stereo (don’t bother), a Dutton (noise-suppressed and horribly dull – perfect if you wish 78s had never existed), Naxos (all right but not great), and Novello with a transfer by Ward Marston, the best until this Biddulph. The transfer under review has clarified the bass line so it doesn’t spread, and it does justice to Sammons’ tonal qualities.

Columbia recorded Sammons and Wood with an unnamed orchestra in a 15-minute truncation of the Concerto in March 1916, months before HMV recorded Marie Hall and Elgar in their competing version, though their truncation was slightly different. It’s clear that Sammons’ conception was secure by this point – he had given his first performance of the concerto two years earlier – and that his tonal qualities were as expressive and powerful. If you have had the chance to hear his first recording, made in 1908, you will hear a café-orientated player using very little vibrato and lashings of portamenti. The change to his sound within these short years is astonishing. This recording has also been reissued lately by Lani Spahr on a Somm disc called ‘Elgar Rediscovered’ and he has been more interventionist in his work resulting in greater definition to the sound. By contrast, Biddulph’s is a more faithful representation of the original.

The recording of the Sonata was the first complete one though there had been an abridged acoustic one by Marjorie Hayward and Una Bourne. Murdoch seems to have been recorded slightly at a remove or maybe the lid was down but it doesn’t much affect the performance which is full of those dramatically expressive and forward-moving drives familiar from the Concerto. The quixotic and firefly elements of the central movement have surely seldom been caught as well as they are here. This has also been transferred by Naxos and Pristine using its ‘XR’ technique.

If you’re considering Sammons’ Elgar this is now clearly the place to come.

The booklet notes – full disclosure – were written by the present writer.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free