Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

The Symphonies

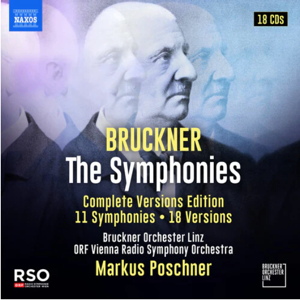

Bruckner Orchestra Linz, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Markus Poschner

rec. 2021-2024, Linz & Vienna, Austria

Naxos 8.501804 [18 CDs: 1070]

What exactly do we have here? This issue is labelled the Complete Versions Edition: 11 Symphonies • 18 Versions. Eleven, because along with Nos. 1-9, we have the so-called Study Symphony in F minor and the Symphony No. 0 in D minor “Die Nullte”. Both have their place in the cycle, as they should. All the enduring great cycles in the catalogue which only include Nos. 1-9 remain essential, but can no longer be seen as complete.

It is also plausible to claim that completeness means just eighteen versions, when one considers the definition of the term by the editors of the ongoing New Anton Bruckner Complete Edition (NBG Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag Wien). Therein, versions of Bruckner’s symphonies are based on historical occurrences “such as a performance, printing, or dedication or other event that denotes closure on a specific phase of Bruckner’s work on a composition”. That excludes anything edited by his pupils without his explicit approval, and disallows the variants he wrote in his score on the way to a new version as just defined.

This is a laudable – but possibly doomed – attempt to produce clarity about Bruckner versions. William Carragan’s fine book Anton Bruckner Eleven Symphonies; A Guide to the Versions (Absolute Publishing 2020) (review) posits three versions of the First Symphony, whereas there are just two in this box, “Linz” and “Vienna”; the authoritative discography at abruckner.com lists six “versions”. Suppose this settles down, and eighteen versions become an established listing, with the term as precise as in the foregoing definition. That can only last until the next trove of undiscovered Bruckner material emerges (if only). No matter. For many collectors, it is a more than an acceptable claim to completeness to have two versions each of the First, Second, and Eighth Symphonies, and three each of Symphonies Three and Four.

Markus Poschner conducted the Bruckner Orchestra Linz and the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra in these performances, first released individually on the Capriccio label and recorded in 2021-2024. The project was to be completed for the two-hundredth anniversary of Bruckner’s birth. Naxos has put the 18 original Capriccio CDs in one box. The 1865 Scherzo rejected from Symphony No. 1, and the 1876 Adagio removed from Symphony No. 3 are included on the relevant discs. There are 18 discs, since not even the 82-minute recording of the 1887 Eighth spills onto a second disc. Paul Hawkshaw’s authoritative and much-admired notes from the original Capriccio releases appear in a single booklet, in English and German. There is full listing of the box contents on the back of the box, and each disc has an attractive cardboard sleeve with the movement timings on the reverse.

This edition won Markus Poschner and his two orchestras an International Classical Music Awards “Special Achievement Award” in 2024. The ICMA website says: “This complete set of editions of Bruckner’s symphonies is an exceptional project because it questions our listening habits and musical tradition [my emphasis]. It combines musicological research with artistic excellence, while bringing together Austria’s leading musical institutions. In short, the sound of Bruckner, yet innovative too.”

That is a serious source for such approbation, but the individual performances have had a slightly mixed reception, at least in English-language sources such as Gramophone and MWI. The Study Symphony of 1863 is called thus because it was part of, and came at the end of, Bruckner’s extended formal musical education when he was nearly forty years old. It is far more than an exercise, and well worth hearing. It might have helped its cause if it were simply called F minor Symphony or Number 00. Often referred to as Mendelssohnian, it reflects the classical and early-Romantic models Bruckner had been studying, but still has embryonic elements of his later style. This alert performance adopts swifter than usual tempi which suit it well. Both MWI (review) and Gramophone broadly welcomed it. It runs for just 33 minutes, compared to 42 in Simone Young’s Hamburg recording on Oehms (on SACD, still a favourite of mine). Young takes the repeats in the outer movements, unlike Poschner.

Symphony No. 0 in D minor “Die Nullte” has been even more warmly received by MWI (review), and contends with the finer sound of Young’s SACD. She takes longer in all movements save the scherzo, 7:43 against Poschner’s imposing 8:10.

Symphony No. 1, actually written before No. 0, has two versions from many years apart, the “Linz” version of 1868 and the “Vienna” version of 1891. MWI (review) approves the performance of the former. The reviewer notes: “Fortunately, this is a symphony which can take brisker tempi”. Even so, he prefers Gerd Schaller’s account. Similarly, I maintain my loyalty to Simone Young’s recording, even though her 49-minute reading can sound a bit too steady after Poschner’s lively and attractive 45:24. MWI was less enamoured of the Vienna version, and found both the version and the performance wanting (review). It is, in any case, more rarely found in catalogue and concert hall than the Linz version.

Poschner’s original 1872 version of Symphony No .2 has unusually (uniquely, I think) the Adagio before the Scherzo, as no surviving version of the complete symphony actually has the Scherzo coming ahead of the Adagio, apparently. Gramophone recommends this account, and MWI praises Poschner’s accounts of both versions of the Symphony (review ~ review). Among the attractions of the 1872 version, there is the close of that Adagio, where the horn has a most poetic envoi. It was replaced by the clarinet in the 1877 second version, which is much less atmospheric. (It seems the Viennese horn in Bruckner’s days had a particular instrumental instability with the peak of the phrase, hence the clarinet substitution.)

The Third Symphony has three viable versions. The 1873 score contains some – far from blatant – Wagner quotations, and is 280 pages or 2056 bars long, Bruckner’s longest bar count. The 1877 version removes the quotations and drops to 1815 bars on 262 pages. The 1889 score has still more cuts and alterations on its 202 pages with 1644 bars. For many years, the shortest version was the most recorded and performed. But now it is often felt that the third version is too abridged, with valid passages omitted. So a few conductors are programming the 1877, or even the 1873, version. Here we have recordings of all three.

This recording of the original version is largely dismissed by MWI (review) for reasons of tempo, execution and even engineering. It is easy to hear why, at the outset. The trumpet theme is ineffective; yes, it is marked piano but the first statement of the main theme lacks presence here. After that, the performance grew on me as it proceeded. Gramophone was more considered in its assessment, but did not add it to the recommended pile. Poschner’s oft-remarked swift tempi are a little more extreme here than elsewhere, and he delivers this longest of Bruckner’s scores in 57 minutes. Even Roger Norrington’s brisk account needs 61 minutes, and the usually too slow (for me) Sergiu Celibidache takes 66 minutes. MWI’s reviewer also found little compensation in the performances of the later versions (review ~ review), for the same reasons: mainly, but not only, tempi. Gramophone’s critic broadly agreed with the MWI assessments. If my own listening gave no compelling reason to demur, I am more sympathetic to “modern” swifter tempi for Bruckner, and found things to admire along the way.

Poschner has already published his defence. In Gramophone’s 200th anniversary Bruckner issue of January 2024, a symphony was allocated to each of ten conductors to discuss. Poschner got, or selected, the Third. He observed that No. 3 was the most experimental of all the symphonies. He added: “Unfortunately, few interpreters to date have dared execute the symphony at the right tempo, in neither the first movement nor the finale, where the technical limits of the orchestra are quickly reached.” Clearly, he gave this some thought, and his recordings offer what he considers “the right tempo”. Anyone who auditions the set by sampling the versions of the Third Symphony – the place to start, I suggest – should bear these remarks in mind. (On related current Bruckner performance practice issues, see the last four paragraphs of this review.)

With the Fourth Symphony, the matters improve slightly. I found things to admire in the versions from 1876, 1878-1880 and 1888 (and in the Volksfest finale offered as an appendix to the second version), in interpretation, playing and recording, if never enough to place them above other available versions. MWI was much more engaged by these three versions of No. 4, the first version rather less so (review ~ review ~ review), than by those of No. 3. The first version was unfavourably compared to the recording of it in the three-version compendium by Jakub Hrůša in Bamberg. Gramophone’s Richard Osborne, a seasoned Brucknerian, also dismissed it.

The Fifth Symphony allows us to escape the matter of versions, and here is a standout performance for both Gramophone and MWI. The former wrote of “one of the finest recordings of the Fifth to have come my way for some time”; the latter also found plenty to like (review). Gramophone found things to admire throughout, without quite considering it an essential acquisition. It certainly is a traditional interpretation, no very eccentric tempi except perhaps in the slow movement. The Adagio is marked Sehr langsam [very slow]. Herbert von Karajan’s celebrated recording takes 21:25, while Celibidache drags it out to 24:14. Poschner’s 15:38 might seem to contradict the marking, but two other much-praised live recordings have similar speeds: Gerd Schaller’s 16:27 and Gunter Wand’s 16:13 in his Berlin account. Karajan may most truly get to the heart of the music, but these swifter conductors, Poschner included, also offer poetic readings.

The Sixth Symphony has one version, too. MWI (review) considers Poschner’s account “by no means unsatisfactory”, but clearly prefers other versions, certainly in the first three movements, while finding more satisfaction with the finale. The tempi are only slightly quicker than most recordings I know, and sometimes slower. For example, the Maestoso first movement Maestoso plays for 15:53 versus Karajan’s 15:16. Christian Thielemann, in a filmed interview accompanying his Vienna video recording, refers to the difficulty of conducting the Sixth, not least because of the polyrhythms. Film of the rehearsals shows that even the Vienna Philharmonic players need help, right from the opening bars. Just because Bruckner is now familiar to most European orchestras does not mean it is easy.But the Linz orchestra here play very well, and Poschner directs with energy. I found this as effective in execution as the Fifth Symphonywas, therefore generally persuasive.

The Seventh Symphony has textual issues, but still one recognised version from 1883, here as edited by Paul Hawkshaw for the New Anton Bruckner Complete Edition. Hawkshaw, who wrote all the excellent notes for this issue, is well placed to explain in the booklet the difficulty in creating this edition. Again MWI found it too swift (review). I have a greater tolerance for swifter tempi, and I am curious about the cumulative effect of playing it this way. So, I was quite persuaded, even at times captured, by the performance. Poschner’s overall time is 59:22. Karajan takes 64:16, and Celibidache nearly 80 minutes. Poschner’s interpretation, while still lyrical and expressive, feels more urgent, which some may see as a valid alternative. Gramophone found it “a performance that’s fresh and invigorating but also deeply felt”. In case you are wondering, unrepentant cymbal-bashers like me need not fear; Hawkshaw thinks that the once-disputed cymbals and triangle at the climax of the Adagio are authentic, so they are included here.

With both versions of Symphony No. 8, and Symphony No. 9, Poschner’s series reaches, I feel, a fine climax in three very successful performances. The 1887 Eighth Symphony was greatly admired on MWI (review). Our reviewer referred to its “combination of grandeur, poise and tenderness”. He added, remarking upon the performance of the main difference from the later version, that Poschner “makes a real feature of the fortissimo ending to that (first) movement, virtually bludgeoning the listener into acceptance of its grandeur; it certainly works for me, habituated though I am to the quiet conclusion of the 1890 version.” There is no undue haste here. In fact, Poschner’s timings are very close to those of Simone Young’s 1887 version in her Hamburg series on fine-sounding SACDs. I do not know of a performance better than on this disc of Bruckner’s first thoughts on his mighty Eighth Symphony.

The 1890 Eighth Symphony featured in Gramophone‘s annual Critics’ Choice feature for 2022. They found Poschner’s account one of the finest of recent Bruckner recordings. They referred to “a communicative power that’s enormously compelling” and further noted the “first-class sound and excellent documentation”. MWI (review) described the first two movements as “wholly satisfactory” but felt that the concluding two movements were “the best of this performance”. Unlike the 1887 version, there are many very fine rival recordings, but in my view Poschner’s can at the least reasonably claim to belong in their company.

The Ninth Symphony appears here in its three-movement version, with none of the attempts at a “completed” finale. MWI (review) did not feel it displaced any of the favourite accounts but was enjoyable and finely played. Gramophone regretted “unmarked crescendos […] in the final minute of the first movement” but considered it “otherwise a powerful and involving interpretation” with “weight and momentum”. I found it a very satisfying account, with many an attractive detail and some fine playing, a worthy pinnacle to the whole of this truly complete eighteen-version series. It is a superb contribution to the composer’s anniversary celebrations, enhanced by the fine playing of both orchestras, impressive sound, and outstanding documentation.

I hope to have said enough, and to have directed readers to weightier authorities, for any collector to judge whether this is a set they wish to own, or at least investigate. If so, there is no need to read further. But perhaps I can close with some thoughts on the wider context of these performances, drawing on serious academic and musicological contributions. There is an increasing partisanship nowadays inseparable from Bruckner criticism and appreciation. It is too easy to say there are two schools, but there is surely a range between what one commentator called “the mystics and the modernizers”.

For some, the former school – broad tempi and monumental style – has its roots in the Austro-German ideology of the 1930s. Julian Horton’s book Bruckner’s Symphonies (Cambridge 2004) examines the “Nazi appropriation of Bruckner”, and quotes Bryan Gilliam who wondered if “important post-war Bruckner interpretations (exemplified by slow tempi and lush harmonies) have unwittingly carried over this phenomenon of Bruckner as Nazi religious icon”. Leon Botstein, a conductor and scholar, wrote in his Music and Ideology: Thoughts on Bruckner (Musical Quarterly, 1996) of ways to rethink Brucknerian performance practice: “The first is to reconsider the source and character of the monumentality of Bruckner’s symphonic work. It may be that the aspects that appealed to the Nazis are those that demand rejection. A Schubertian Bruckner, fleet in pacing, lyrical, flexible, and transparent intimbre, is long overdue.” Botstein concludes: “These qualities, rather than the somber, dour, and frightening dimension that emerges from the ‘classic’ Bruckner readings of Furtwangler, Karajan, and Wand, are in short supply in performances of Bruckner.”

To be sure, these view are controversial. I mention them here because these aspects of Bruckner scholarship do touch on the history of performance style, and are often overlooked in connection with recent approaches on record. Harry Halbreich considered tempo flexibility, as indicated by markings added by the first editors who had contact with Bruckner, and later removed. He asked whether a unified – relatively inflexible – tempo is really needed in Bruckner. His firm negative finding has corroboration in the composer’s letters. John Williamson’s chapter Conductors and Bruckner in the Cambridge Companion to Bruckner shows the evolution in Bruckner conducting to be complex. Swifter, flexible, modernist Bruckner performance has its roots in Wilhelm Furtwängler, the younger Karl Böhm, Bruno Walter, Jascha Horenstein and Eugen Jochum – though not in all of their later recordings.

Williamson considers some recordings and movement timings, and concludes: “Within the style that has evolved since the fifties, there is both a mystic-monumental approach and a swifter alternative, but both have been increasingly caught up in the search for a unified tempo which may never have been Bruckner’s intention.” In his 2012 booklet note to Carl Schuricht’s recording of Symphonies Nos. 8-9, Williamson writes of his characteristic tempo fluctuation: “this ebb and flow came from […] instructions included in the published edition of 1892 (of the Eighth Symphony). Benjamin Korstvedt has argued persuasively that these simply make explicit the expressive inclinations of most conductors of the late 19th century.” The so-called modernizers, of whom Marcus Poschner is clearly one, might in effect be aiming to restore a lost authenticity.

Roy Westbrook

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Contents (the original Capriccio volume number, orchestra and catalogue number; the conductor in all recordings is Marcus Poschner)

Symphony in F Minor, WAB 99, “Study Symphony” (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 18; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8098

Symphony No. 0, ed. L. Nowak (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 3; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8082

Symphony No. 1, 1868 Linz version, ed. T. Röder (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 11; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8092

Symphony No. 1, 1891 revision, ed. G. Brosche, and Scherzo, 1865 (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 15; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8094

Symphony No. 2, 1872 version, ed. W. Carragan (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 12; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8093

Symphony No. 2, 1877 version, ed. P. Hawkshaw (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 9; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8089

Symphony No. 3, the original 1873 version, ed. L. Nowak (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 5; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8086

Symphony No. 3, 1877 version, ed. L. Nowak, and Adagio, 1876 (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 16; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8095

Symphony No. 3, 1889 version, ed. L. Nowak (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 13; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8088

Symphony No. 4, “Romantic”, 1876 version, ed. B. Korstvedt (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 6; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8084

Symphony No. 4, “Romantic”, 1881 version, ed. B. Korstvedt (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 4; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8083

Symphony No. 4, “Romantic”, 1888 version, ed. B. Korstvedt (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 8; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8085

Symphony No. 5, 1878 version, ed. L. Nowak (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 10; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8090

Symphony No. 6, 1881 version, ed. R. Haas (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 1; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8080

Symphony No. 7, ed. P. Hawkshaw (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 14; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra) C8091

Symphony No. 8, original 1887 version, ed. P. Hawkshaw (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 7; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8087

Symphony No. 8, 1890 edition, ed. L. Nowak (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 2; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8081

Symphony No. 9, 1894 version, ed. L. Nowak (Complete Symphony Versions Edition, Vol. 17; Linz Bruckner Orchestra) C8096