Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber (b.1948)

Requiem (1985)

Samuel Barber (1910-81)

Adagio for strings (1938)

Soraya Mafi (soprano); Benjamin Bruns (tenor); Florian Markus, Hendrik Brandstetter (trebles)

Tolz Boys’ Choir; Bavarian Radio Chorus

Munich Radio Orchestra/Patrick Hahn

rec. live, 13-15 June 2023, Herz-Jesu Kirche, Munich (Requiem): studio, 1-3 December 2021, Studio 1, Bavarian Radio, Munich (Barber)

BR Klassik 900352 [50]

When Andrew Lloyd Webber originally penned his Requiem back in 1985 it was a decided anomaly in the realm of music: a forbiddingly intense work distinguished by startlingly discordant choral harmonies in the style of Stravinsky or Bartók, surmounted by a trio of soloists of a decidedly mixed nature, which then defied expectations (as did so much of Lloyd Webber’s earlier music) by achieving considerable commercial success especially when one number, the eminently approachable Pie Jesu, actually achieved pop status as a single release. The first performance in New York under Lorin Maazel was relayed worldwide on television, and a studio recording of the complete work, with the same soloists and conductor as that première, also made its mark in the charts. The featured soloists included Plácido Domingo at the peak of his powers, albeit challenged in places by the forbiddingly high tessitura and some eccentric rhythms; the composer’s then wife Sarah Brightman, who was at the time bidding for a career in the opera house with roles such as Violetta in La Traviata but whose reputation was ultimately defined by her assumption the following year of Christine in The Phantom of the Opera; and the boy treble from Winchester, Paul Miles-Kingston, who may have lacked the sheer glamour of near-contemporary rivals such as Alun Jones or Jeremy Budd but whose slightly husky tones had a distinct charm which blended well with the more sophisticated style of Brightman.

Such indeed was the success of this first recording that there seems (apart from a solitary Melodiya live recording from Lithuania in 1989) to have been little appetite to issue a rival, suggesting that it would have been difficult to surpass the original. This new issue takes advantage of a series of live performances in Munich in June 2023 to bring us an alternative rendition of the work, but it has to be observed immediately that it gets off to a rather unsteady start with the boy treble Florian Markus lacking the personality of Miles-Kingston and sounding indeed slightly querulous on his top G in the opening phrases. On the other hand Soraya Mafi and Benjamin Bruns are a better-blended match for each other in the remaining solo parts than were Brightman and Domingo, the latter being conscientiously careful not to dominate his less experienced soprano although also sounding more naturally Latinate in his command of the text. But the more careful balance between voices in this new recording also entails some losses. The sense of challenge to the soprano from her fellow soloists is lacking; and Mafi totally fails to rise to the composer’s instruction in the closing pages of the Hosanna that she should sing ff declamato e feroce at the sudden eruption of the words “Dies irae, dies illa”. The result is anodyne, well-integrated but lacking in any sense of drama.

But should we indeed be looking for a sense of drama, in what is avowedly a liturgical setting of the Latin mass composed in memory of the composer’s father? Well, in the first place Lloyd Webber has deliberately altered the order of the Latin text in several places in order to achieve heightened contrast and excitement. Secondly, as the booklet note by Christian Thomas Leitmer here reveals, there was apparently a programme underlying the music itself, involving an incident during the Cambodian War where a young boy was forced to sacrifice himself in a vain attempt to save the lives of his father and sister. This was an entirely novel concept to me – I cannot recall any references to such a subtext in any of the discussions regarding the work at the time of its first performance – and the booklet note is maddeningly imprecise about supplying any further details. But at all events such associations seem to be very far away from the precise and brisk but somewhat bloodless performance which the music receives here.

The sound is excellent and well balanced, although the woodwind solos are somewhat recessed; the startling eruption of the discordant organ in the final bars drowning out the repeated phrases of the boy soloist is superbly managed. Although the recording was made during live performances (spread over three days), there is no evidence of the presence of an audience, and no applause after the extended fade-out in the final bars. Instead the orchestra moves immediately into Barber’s Adagio, given a flowing performance that does full justice to the exquisite melodic lines without extracting from them the full measure of anguish that one experiences with – for example – Bernstein. Although the juxtaposition of the two works with their funereal associations seems to make some sort of sense, they do to a large extent inhabit very different worlds (the plangent violins in the Barber notable by their entire absence from the Lloyd Webber score) and one gets the uneasy feeling that the coupling has been dictated more by the popularity of the two works concerned than any sense that they form a consolatory unit.

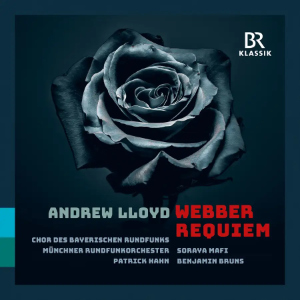

The presentation of the single disc, which even with the addition of the Barber remains somewhat short measure, is well done with full texts and translations into English and German; the cover design too is a definite improvement on the decidedly utilitarian première CD issue. In terms of the performance itself, it may be noted that Hahn briskly shaves nearly three minutes off the 44-minute duration of the work in Maazel’s pioneering version, and that at the same time this is even further away from the composer’s estimate of 46 minutes as given in the score. Christian Thomas Leitmer’s booklet note delivers a somewhat startling critical judgement on the music – “The success of Lloyd Webber’s eclectic experiment is debatable. At times…the fragile edifice crumbles under the centrifugal force of its parts” – but at the same time he admits that at other times “the colourful patchwork of seemingly incompatible elements produces a wonderful harmony of a higher order.” It seems that the ability of the work to divide critical opinion remains, after nearly forty years, as strong as ever.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free