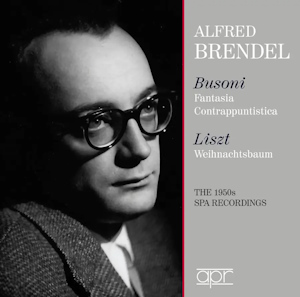

Alfred Brendel (piano)

Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

Fantasia Contrappuntistica, BV.256 (1910)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV.639 (arr. Ferruccio Busoni, BV B27 No 5, 1898)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Weihnachtsbaum, S.186 (1874-76)

rec.1952-1953, Vienna (exact dates and venue not known)

APR 5655 [79]

Alfred Brendel’s enthusiasm for both Busoni and Liszt is of very long standing, and these recordings are among the earliest he has made. The Busoni, in particular, has had legendary status in that it is the only recording he made of Busoni’s largest solo piano work, the Fantasia Contrappuntistica, and until now had never been reissued. Here the Busoni has been paired with Brendel’s early Liszt recording, the CD thereby containing what were originally two LPs.

The Fantasia Contrappuntistica derives from Busoni’s study of the last, unfinished fugue from Bach’s Art of Fugue. As published, it successively expounds and develops three subjects, but breaks off when they start being combined. In 1880 the musicologist Gustav Nottebohm showed that they would also combine with the motto theme of the whole work and deduced that Bach would have included and developed the fourfold combination had he lived to complete it. Busoni learned of this on his visit to the USA in 1910 from his friend, the composer and teacher Bernhard Ziehn. Busoni then made his own completion of the fugue, using the expanded chromatic idiom Ziehn had proposed, and inserting an intermezzo with three variations and cadenza before the culminating combination, which also draws on other parts of the Art of Fugue. He published this in 1910 in the U.S. A. as Grosse Fuge but, on his return to Europe, added the third of his Elegies as an introduction. The result he now titled Fantasia Contrappuntistica, and called this the edizione definitiva. However, he went on to make two further versions. The edizione minore of 1912 has a different opening and a simpler ending, while the two piano version of 1922 introduces further refinements but also cuts.

Brendel plays the 1910 edizione definitiva, as indeed do most pianists who attempt this work at all. (Brendel does not include the optional passage given in an Appendix. For Nicoara’s recent recording of a revised version of the score which includes this and other revisions see review here.) Busoni was himself a virtuoso pianist and it is a very demanding work, with some quite impractical passages and one famously impossible trill. He also does not incorporate Bach’s work unchanged; that was never his way. He makes some cuts, adds notes such as a deep pedal D at the beginning of the first fugue, and makes chromatic and other alterations, all of which serve to assimilate Bach’s work more nearly to his own idiom.

Brendel’s performance is very impressive. In addition to his absolutely secure technical grasp, he shows a fine feeling for the kind of sonority Busoni wanted. Although there are some tremendous climaxes, a good deal of the work is actually very quiet. In the opening Preludio corale it is also important that the accompanying figures are kept in the background so that the main themes can sing out. In the fugues, the polyphony is absolutely clear and in the more obviously virtuoso passages towards the end he retains control of his tone without indulging in the forceful banging I have heard from some pianists.

As an encore after this, Brendel gives us one of Busoni’s transcriptions of Bach’s chorale preludes, originally written for organ. This is a short and gentle work but the texture is very rich. Brendel carefully obeys the instruction to keep the bass line dolce e sostenuto and observes the instruction on the second page to play it ppp.

Liszt’s Weihnachtsbaum (Christmas tree) cycle is one of his late works. The twelve pieces are based on Christmas carols and other folk songs. They are rather strange. Each one begins quite simply, often with a melody in single notes. This is then progressively elaborated. This can be quite charming, as in The Shepherds at the Manger, which uses the carol In dulci Jubilo. It can also be very forceful, as in Adeste Fideles, subtitled March of the Three Holy Kings, i.e. the Magi. Although Liszt had long abandoned his interest in virtuosity for its own sake, he nevertheless wrote some very demanding music, such as the fast left hand octaves in the Scherzoso subtitled Lighting the Tree. There are also two bell pieces, a march and a mazurka. Although the pieces are interesting, I do not think they make a particularly satisfying whole. However, Brendel’s sympathy with Liszt makes the best of them. This was the first recording of the work.

This reissue is based on the original LP recordings and we have to thank Andrew Hallifax for remastering and sound restoration. However, the recording remains that of the early 1950s and allowances have to be made: it simply does not have the body or depth of modern piano recordings and climaxes are congested. However, it can certainly be listened to with pleasure. Brendel himself contributes a short essay to the booklet. This is one for Brendel enthusiasts, who will not be disappointed.

Stephen Barber

Previous review: Rob Challinor (October 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free