Minimalist

Contents listed after the review

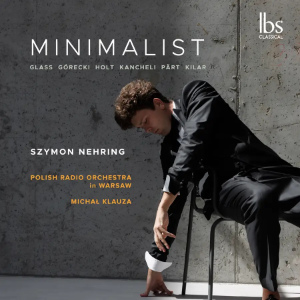

Szymon Nehring (piano)

Polish Radio Orchestra in Warsaw/Michał Klauza

rec. 2024, Warsaw, Poland

IBS Classical IBS132024 [79]

This well filled disc released under the title ‘Minimalist’ gathers together a number of composers, one American and six European, who could loosely fit under the banner. Since Michael Nyman coined the term in the 1960s, it has become used for all sorts of music that uses repetition as a key element. Terry Riley, Philip Glass and Steve Reich are the most well-known Americans who still fit comfortably, with some exceptions, under the banner. The younger John Adams has taken minimalist traits and added a Romantic sensibility and sense of scale to his hugely popular works. So too, the Europeans on this disc have all at some point written music that could be considered minimalist. I am not sure that the works by them presented here are from their minimalist periods. To repetition and simple harmonic movement, the works here have added back ‘traditional’ elements of melody, drama and theatre that 1960s minimalism did not have.

Philip Glass’s series of 20 Etudes (1994-2012) have been taken up by a number of concert pianists, notably Yuja Wang, who often programmes No 6 as an encore. Here we have the fourth from the first series. It has all the Glass hallmarks, with an arpeggio left hand and a mainly chordal right. It uses the rhythmic interplay of alternating grouping of two threes or three twos and never outstays its welcome, which is not always the case with Glass. Mr Nehring gives a brooding interpretation that never descends into sentimentality. The booklet notes compare these to Ligeti’s Etudes. There is no comparison. The Glass were mainly written as studies to improve his own far from virtuoso technique, while the Ligeti were written as virtuoso modes of composition for only the most fantastically gifted pianists. Mr Nehring contributes a short ‘bridge’ which cleverly melds material from the Glass and leads straight into the Górecki.

Górecki’s concerto was originally conceived for harpsichord in 1980 but has since then often been performed, as here, on a piano. The composer described the nine-minute work in two movements as a ‘prank’ not to be taken seriously. But was he joking with the remark? The first movement is all Baroque swirls and drama while the second has a chugging motoric accompaniment and brittle humour reminiscent of Shostakovich. Prank or not, it is an entertaining little work. The twenty bars of the same D major chord towards the end pushes the humour, if that is what it is, a little too far but brought a smile to my face. I prefer the work on harpsichord as that combination particularly in the second movement has a manic quality. This is however a convincing performance well on top of the very fast metronome markings, managing to be articulate and dramatic at the same time.

According to the composer Canto Ostinato should last at least two hours so the six minutes or so section here is only a tiny fragment. It is mainly the ‘big tune’ which is hinted at throughout the work but appears fully formed in Section 74. It is indeed a wonderful melody, but it belongs in the whole work, not as an extract. Rather like only having the ‘big tune’ from Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, I prefer the entire work, which is a masterpiece of the genre. The booklet gives no indication that it is a fragment of a much larger work.

Giya Kancheli was a Georgian composer who after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 lived first in Berlin and then Antwerp. His music is hard to categorise, minimalist does not cover it. In most works, there are long passages of slow chords interrupted by violent, enigmatic outbursts. There is often a feeling of leave-taking, lamentation, and commemoration and a number of his works are memorial pieces. This Valse Boston for piano and strings is no exception. Dedicated “to my wife with whom I’ve never danced”, it is profoundly sad.

The traditional Boston Waltz was a languid variant of the Viennese Waltz, which became popular in the 1920s. The dance steps included much balancing or suspension for the dancers and there is much musical suspension here. Where Ravel’s La Valse depicted the apotheosis of the dance, this is a waltz where destruction has already taken place. The ballroom is covered in rubble and the dancers wistfully move around the carnage. Very much the type of dance that would have appeared in one of Pina Bausch’s dance theatre works. The overall mood is one of unbearable sadness and loss with the occasional outburst of rage against something tragic, whatever it is. Anyone looking for a waltzlike ¾ will be disappointed, for if it is there, it is well hidden. The stasis, as in the works of Morton Feldman, becomes almost unbearable until here and there is the occasional outburst. A tiny galloping figure appears only to disappear into nothing, appearing briefly later as though it left the picture and then had second thoughts. Kancheli wrote a great deal of film music, and I can see this working well as an underscore to a dystopian epic. As a concert work, even with a tremendously dedicated performance as is given here, I found it hard to get into. For me, it is too enigmatic and untouchable.

Arvo Pärt who recently turned ninety is far better known than Kancheli. Often grouped into the minimalist subcategory of ‘holy minimalism’ his deeply held religious faith has underpinned most of his works. Variations zur Gesandung von Arinuschka (Variations for the Healing of Arinushka) was one of the first works of his mature style employing his tintinnabulation technique. It was written for the composer’s daughter Ariina who was recovering from an appendix operation. The piece contains six short variations, the first three of which are in minor key and the other three in major. It is all very tuneful and pleasant. It is followed by the tiny Fur Anna Maria, which was written for the tenth birthday of a family friend and is unusually for this composer cute and playful. What is impressive about Mr Nehring’s playing is that he lavishes as much attention on these tiny works as he does the weightier ones on the disc.

Wojciech Kilar was born in Lviv (once in Poland, now in Ukraine), and spent most of his life in the city of Katowice. He showed early musical promise and studied in his homeland until 1959 when, like many before, and after, he went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger. He developed an international reputation for his film scores notably Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (1992), Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady (1996), and three films directed by Roman Polanski—Death and the Maiden (1994), The Ninth Gate (1999), and The Pianist (2002). For the concert hall, he wrote over 30 individual works, including 5 symphonies, 2 piano concertos, all of which demonstrate a theatrical flair. The concerto recorded here is the first, the second appearing in 2011. Written in 1996-7 it was premiered by its dedicatee, the Swedish pianist Peter Jablonski.

It is a marvellous addition to the piano concerto repertoire, being a perfect synthesis of all things rhythmic, minimalist, and theatrical. In the early 60s, Kilar was writing in the style of the Polish avant-garde. But gradually he began to use a more pared down musical language, in which dense masses of sound, often utilising the lower range instruments, serve as a backdrop for romantically inspired melodies.

The work itself is unconventional in structure, opening with a slow and mellow Andante movement that’s almost trance like. The piano’s opening solo lures us in with its serene, calmly repetitive motifs before the violins enter with a beautiful, slow drawn-out melodic elaboration of the piano writing. A build up of thickening sound and additional layers is brief, and the first movement closes as quietly as it began.

The second movement begins with a solemn plain chant inspired chorale introduced by the soloist at the opening and then taken up by the strings. They introduce this magnificently and I have to confess that I realised I had stopped breathing when it started. The architecture of the movement has the perfection of a mediaeval cathedral which gradually builds to an immense climax of radiant power which the engineers have done a great job in capturing.

All of the calm is rudely swept away in the final movement, a high energy Toccata which owes much to early Ginastera with its pounding dance rhythms and piano clusters. It is a breathless tour de force. I wonder if the composer was thinking of the Gorecki work, as the final pages feature obsessive chords, which for the pianist are all over and at opposite ends of the keyboard and are a nightmare to coordinate. They culminate in a tight little note cluster, repeated sixty-seven times, before the work ends with a cheeky cadence in A major and guaranteed to have an audience on its feet. In the finale Mr Nehrig is 25 seconds slower than Peter Jablonski in his recording of the work and it makes a difference. The demonic force is held back instead of allowed full rein.

Mr Nehring has a wonderfully rich tone and a subtle pedal technique. Even in the works where he is playing the same pattern over and over, one has the impression that he is shaping each repetition anew and not merely repeating it. Mr Klauza likewise keeps the orchestra sounding fresh and alert even when they are playing repeated material. They have a wonderfully rich sound, whether in the many lyrical passages or the brutal pounding rhythms of the Gorecki or Kilar.

Paul RW Jackson

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Contents:

Philip Glass (b. 1937)

Etude No 4 (1994)

Szymon Nehring (b. 1995)

Bridge (2024)

Henryk Górecki (1933-2010)

Concerto for Piano and Strings (1980)

Simeon ten Holt (1923-2012)

Canto Ostinato (1976)

Giya Kancheli (1935-2019)

Valse Boston (1996)

Arvo Pärt (b. 1934)

Variations zur Gesundung von Arinuschka (1977)

Für Anna Maria (2006)

Wojciech Kilar (1932-2013)

Piano Concerto No 1 (1997)