Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880)

The Tales of Hoffmann

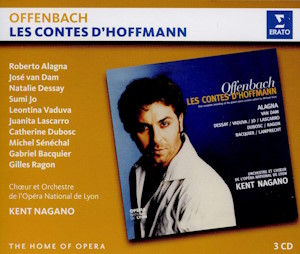

Hoffmann: Roberto Alagna (tenor)

Olympia: Natalie Dessay (soprano)

Giulietta: Sumi Jo (soprano)

Antonia: Leontina Vaduva (soprano)

Nicklausse/Muse: Catherine Dubosc (mezzo-soprano)

Lindorf/Coppélius/Dapertutto/Dr Miracle: José van Dam (bass-baritone)

Spalanzani: Michel Sénéchal (tenor)

Crespel: Gabriel Bacquier (baritone)

Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra National de Lyon/Kent Nagano

rec. 1994-96, Opéra de Lyon, Lyon

Erato 2564 648322 [3 CDs: 172]

This set was first favourably reviewed on this site in 2011 by Simon Thompson when it was issued on the Erato Opera Collection label as a budget item with no libretto, just a tracklist, a track-by-track synopsis and a link to a French libretto – in brief, pretty basic, with no word about the edition used apart from stating that this is Michael Kaye’s edition (of 1993, with recitatives rather than spoken dialogue), This reissue is identical. I made oblique reference to it when in 2015 I reviewed the Autograph box set of José van Dam’s collected recordings 1974–1997, also on the Erato label, calling his assumption of the four villains in Cambreling’s Les contes d’Hoffmann “a tour de force”.

While it is not as long as Sylvain Cambreling’s recording of the Oeser edition which imports music from other works by Offenbach such as Die Rheinnixen and runs to nearly three and a half hours (plus appendices), the use of sung recitative here inevitably slows down the action. To combat this, Nagano adopts a brisk pace. The Lyon chorus and orchestra are excellent – the best I have heard – and the whole production carries the mark of thorough preparation and rehearsal. It is still something of a halfway-house, however, in that while the four “forces of evil”, Hoffmann’s nemeses, are taken by one singer, van Dam, Offenbach’s intention that all three incarnations of his unattainable love should be sung by one singer are ignored. This is, of course, essentially a practical solution, in that while it might be true that the lead soprano of Verdi’s La traviata must have a different voice for each act, that challenge is even more acute in the case of The Tales of Hoffmann – hence the only two major studio recordings to cast one soprano in all three roles and one baritone as all four villains is Bonynge’s in 1971 with Joan Sutherland and Gabriel Bacquier, and Rudel’s in 1973 with Beverly Sills and Norman Treigle. Ozawa in 1986 has Edita Gruberová throughout but two different baritones and two different bass-baritones as the baddies. Bonynge’s recording remains a great favourite with collectors; Ozawa’s much less so for obvious reasons: Gruberová’s shallow soprano was hardly suited to encompass the range of all three lead female roles and if Sills was recorded a little late, more damaging are the lumpy assumptions of Treigle, who might have been a compelling presence on stage as a “singing actor” but in purely vocal terms his clumsy voice does not translate well to the solely audible medium of an audio recording.

Nagano’s cast is starry, but the first soloist we hear, Catherine Dubosc as the Muse, later Niklausse, is merely fine and not a patch on Bonynge’s much richer-voiced and more characterful Huguette Tourangeau. José van Dam as Lindorf – and, of course, later all the adversaries – is another matter: suave, inky-voiced and subtly menacing, he is ideal, with none of the comparatively rougher-voiced vocalisation of Gabriel Bacquier, now “relegated” here to the role of Crespel and sounding pretty good, too, for a man in his seventies. Roberto Alagna’s entrance pins backs our ears: he is in best voice, impassioned and resonant. His slightly husky timbre is not quite as seductive as the young Domingo’s sappy sound, but the high notes come more easily – including a cracking B-flat in the Olympia act – and he is completely inside the role of the unstable, lovelorn Romantic. Even minor passages such as the exchange of insulting pleasantries between Hoffmann and Lindorf are a delight when delivered by two such accomplished singers – and of course, both have perfect French, which cannot be said for Domingo, whose French accent is always Hispanic-tainted. Apart from the orchestration, there is in fact very little difference in the actual content of the first three acts between the Oeser and Kaye editions except for some minor variations in the sung dialogue, whereas Acts IV and V are almost completely different.

Act II hasn’t the most beguiling music until the entrance of Olympia but old hand Michel Sénéchal makes the most the role of Spalanzani, even if Gilles Ragon’s Cochenille is not as amusing as Hugues Cuénod’s for Bonynge. Natalie Dessay made something of an early reputation singing highly demanding coloratura roles such as Olympia, the Queen of the Night and Zerbinetta and she is very good – agile, accurate, with a top D-sharp and an even more astonishing, stratospheric top G – but she is not as glamorous or exciting as Joan Sutherland, I think, whose voice was bigger. Alagna’s passionate outbursts to the “automate” are superb, though.

Act III centres on Leontina Vaduva’s richly sung – if rather anonymous – Antonia. Likewise, Gilles Ragon is again competent but banal as Frantz, making one regret his inability to derive as much fun from the role as Cuénod. However, the cumulative tension created by the combination of Nagano’s taut direction, the trio of van Dam, Bacquier and Alagna, Doris Lamprecht’s spectral Mother and Vaduva’s impressive vocalisation, all building towards Antonia’s death, makes for truly thrilling results; for me this act is the highlight of the recording.

Act IV opens with the most famous and popular number, the Barcarolle. Perhaps I am too habituated to more traditional orchestral and vocal arrangements, but its opening is to my ears oddly scored here with a solo oboe and flutes – I have no idea if that was what Offenbach intended but it sounds too lean compared to what I am used to. It is ironic that this most famous number was never originally in this work; it was imported from Die Rheinnixen. Nagano sets too brisk a tempo and Dubosc’s mezzo is insufficiently voluptuous; Sumi Jo’s lovely, shimmering soprano brings some compensation and her coloratura is stunning; this act belongs to her. Alagna delivers “Que d’un brûlant désir” ardently, too. This act is completely different from the Oeser edition and surely any lover of this opera will regret the omission of “Scintille diamant” from the Choudens edition.

For all that I thoroughly enjoy this recording, especially the two central performances here by Alagna and van Dam – but also the accomplishment of their co-singers like Vaduva – there is a reason why the less textually correct Bonynge recording retains its place in the affections of collectors, even if Bacquier is not ideal; it has a special, distinctive character and a unity conferred upon it by its use of the same two singers for the multiple roles of heroine and villain; furthermore, several supporting roles seem marginally under-characterised compared with the gallery of vivid personalities in the Decca set.

Ralph Moore

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Other cast:

Andrès/Cochenille/Pitichinaccio/Frantz: Gilles Ragon (tenor)

Luther: Jean-Marie Frémaux (baritone)

Nathanaël: Benoît Boutet (tenor)

Schlemil: Ludovic Tézier (baritone)

Stella: Juanita Lascarro (soprano)

Wolfram: Jean Delescluse (tenor)

Hermann: Gérard Théruel (baritone)

Wilhelm: Christophe Lacassagne (bass-baritone)

Une voix de la tombe (La mère): Doris Lamprecht (mezzo-soprano)

Le capitiane des Sbires: Marc Fournier (bass)