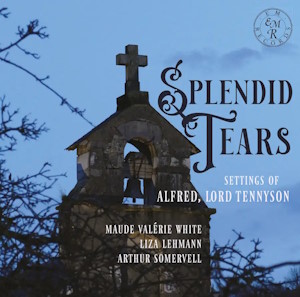

Splendid Tears

Settings of Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Maude Valerie White (1855-1937)

Four songs from Tennyson’s In Memoriam (1885)

Lisa Lehmann (1862-1918)

In Memoriam – A Song Cycle (1899)

Sir Arthur Somervell (1863-1937)

Cycle of Songs from Tennyson’s Maud (1898)

Brian Thorsett (tenor)

Richard Masters (piano)

rec. 2022, Creativity and Innovation District LLC Building, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, USA

Texts included

EM Records EMRCD087 [80]

This generously filled CD contains songs in which three English composers set poetry by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892). There’s considerable rarity value here; the songs by Maude Valerie White have never been recorded before while this is the first time that a tenor has recorded either the Lehmann or Somervell cycles. The performers are two American musicians, both self-confessed Anglophiles, who are not only established concert artists but also colleagues, as faculty members, at Virginia Tech’s School of Performing Arts. Richard Masters’ name may also be familiar to some readers as a contributor of reviews to this site.

Both White and Lehmann extracted verses from Tennyson’s In Memoriam A. H. H. (1850), in which he pays tribute to his close friend, the poet Arthur Henry Hallam (1811-1833); they had met while students at Cambridge University. Hallam’s sudden death in 1833 from a cerebral haemorrhage was a great blow to Tennyson. There is no overlap between the lines selected by the respective composers.

In their jointly-authored booklet notes, Thorsett and Masters acknowledge that Maude White’s songs are the “most conservative [on their programme] in terms of harmonic language, owing a clear debt to Mendelssohn”. I wouldn’t disagree, but they are nonetheless, worth hearing. ‘I sometimes hold it half a sin’ is a strophic song with an air of gentle melancholy. The second song, ‘’Tis better to have loved and lost’ features a rippling, Mendelssohnian piano part and benefits from the expressive way in which Thorsett sings it. Next is ‘Love is and was my Lord and King’. This is a more impassioned offering; it’s ardently sung, while Masters projects the piano part strongly. The last of the set is ‘Be near me when my light is low’. This is the longest of the four songs. The music moves from a quietly atmospheric setting of the first stanza, through powerful entreaty in the next two verses to an impassioned conclusion (verse 4). These songs may not be great songs – I wish, for one thing, that White had curbed a little her tendency to repeat words. However, they’re all well-crafted and White responds with conviction to Tennyson’s words. Thorsett and Masters give very committed performances and show the songs in the best possible light. Incidentally, one interesting snippet that I picked up from the booklet was that prior to 1940, Maud White was the most-performed female composer at Henry Wood’s Promenade concerts; over 100 performances of her music were given there.

Lisa Lehmann was herself a singer – I learned from the booklet that she was at one time a pupil of Jenny Lind – and she pursued a successful career as a solo soprano between 1884 and 1894. She married in 1894 and retired from performing, thereafter focussing her musical activities on composition. Her background as a singer is relevant, I think, in assessing her song cycle In Memoriam because it seems to me that the songs are well written for the voice – and for the piano, too. I’d not heard these ten songs before. I think one comment I should make is that anyone who thinks that these songs, being the work of a late Victorian female composer, will be simply polite or genteel will be in for a (pleasant) surprise; there’s passion aplenty in these songs; Lehmann responded keenly to the strong emotions in Somervell’s poetry. Furthermore, the piano writing is often powerful, indeed turbulent. Lehmann is much more inclined to big gestures in the piano part – and in the vocal line – than White. I don’t make that latter point as an implied criticism of Whites music, by the way; it’s just a stylistic difference, at least to my ears.

When I look through the notes I’ve made for each of Lehmann’s songs, I see certain words such as ‘urgency’, ‘impassioned’ and ‘dramatic’ keep recurring. That’s not to say, though, that everything is high-voltage. For instance, the fifth song, ‘When on my bed the moonlight falls’ is quite introspective, a quality that is underscored by the thoughtful, subtle way in which Thorsett and Masters perform it. The following song. ‘I cannot see the features right’ displays both sides of Lehmann’s approach to the poetry. The first two stanzas are set to really urgent music but then the concluding stanza is much calmer in tone, as is the piano postlude. Much earlier, there are several examples of Lehmann’s impassioned side. The cycle begins with ‘I sing to him’ which is a very passionate setting. Incidentally, this song opens with an extended, bold piano introduction, splendidly delivered by Masters, which at 1:33 accounts for some 25% of the length of the whole song. Another powerful utterance is the fourth song, ‘Risest thou thus, dim dawn, again; Thorsett and Masters make this song properly urgent and passionate. As the end of the cycle approaches, I very much admire the sensitivity which both performers bring to the final stanza of the penultimate song, ‘Sweet after showers, ambrosial air’ The last song, ‘Who loves not knowledge?’ is a boldly dramatic setting, declamatory in nature. Thorsett and Masters rise to the emotional challenge of the words and music, achieving the desired powerful end to the cycle.

There’s a great deal to admire in Lisa Lehmann’s cycle; clearly, the sentiments expressed by Tennyson struck a chord with her and the result is music of no little intensity. The present performance is a very fine one.

Previously, I’ve only heard Somervell’s cycle Maud performed by baritones. I think I’m right in saying that the most recent recording is the one by Roderick Williams and Susie Allan, issued in 2020. When I reviewed that disc, I owned up that I’d experienced something of an epiphany when I heard the same artists perform the songs live in 2019. Prior to that, I’d felt that Somervell’s cycle was somewhat fusty and Victorian. Williams and Allan opened my ears that day and thereby enabled me to appreciate far more their recording when it appeared. I deliberately have not gone back to that recording prior to hearing the new Thorsett/Masters disc because I wanted to experience for the first time a tenor in these songs as something fresh.

Somervell compressed Tennyson’s text significantly for his cycle. He had to do so because Tennyson’s Maud (published in 1855) consists of no fewer than twenty-eight poems. Somervell’s editorial work reduced this to manageable proportions – there are 13 songs in his cycle – and he constructed a narrative, implied at times. I summarised the trajectory of the cycle thus when I reviewed the Williams version. Somervell begins with the narrator lamenting his father’s suicide. He then meets the young Maud and by the time we get to the fourth song, he’s smitten. In time he persuades Maud to ‘come into the garden’; they are surprised by her brother who challenges our hero to a duel. Maud’s brother dies in the duel and, after blaming himself, the narrator, whose name we never learn, effectively has a breakdown and the cycle ends with him resolving to go off to fight in battle. He expects – nay, hopes – to die and to be reunited in death with Maud, who, he tells us, has herself died.

I’ve come to think quite highly of Somervell’s cycle and this new performance confirmed to me the virtues of the musical response, even if Tennyson’s effusive poetry isn’t quite to my taste. Brian Thorsett clearly believes in the songs and he’s backed to the hilt by Richard Masters’ pianism. They convey very well the bitter anguish of the first song, ‘I hate the dreadful hollow’ but they’re equally successful in the gentler, almost innocent third song ‘She came to the village church’; here, Thorsett’s singing is most expressive. Both the singer and, even more so, the pianist really bring out the Schumannesque rapture of ‘Maud has a garden’. I’m glad to say that Somervell’s setting of ‘Come into the garden, Maud’ is streets ahead of Michael Balfe’s parlour song; it’s important to add that in this cycle you get the words and the sentiments in context which, in fairness, Balfe could not achieve in a standalone song. I especially like the delightful light pianism of Richard Masters here. Brian Thorsett sings with appropriate ardour. The last two songs bring the cycle to an intense conclusion. In ‘O that ‘twere possible’ Somervell’s urgent music conveys the narrator’s anguish – Thorsett picks this up really well in his singing. The last word is ‘My life has crept so long’; this song conveys a mixture of dignified sorrow and noble resolve; these artists do it very well.

It’s been very interesting to hear these songs sung by a tenor for the first time. It’s rather like hearing the Schubert song cycles sung by a high or low voice; one is not necessarily “better” – whatever that may mean – than the other; rather, the different voices add differing dimensions to the music. Incidentally, the artists explain in the booklet that all the Somervell songs have been transposed to facilitate performance by a higher voice. It was only necessary to transpose some of the Lehmann songs and one of the four by Maude White.

I enjoyed this album very much. I have been glad to encounter the songs by Maude White and Lisa Lehmann for the first time and to experience the Somervell songs in a new way. The performances are excellent. Brian Thorsett’s voice makes a very positive impression. His diction is crystal clear, he is sensitive to words and music and he sustains vocal lines really well. I’m not sure if he and Richard Masters are regular recital partners but that’s the impression one gets here; Masters is always ‘with’ his singer and he makes a very positive contribution at the piano.

Engineer Michael Briggs has recorded the artists well. The balance between voice and piano is well judged and both artists are clearly heard. I might have preferred a slightly warmer acoustic but that’s a minor point. The notes, authored by the performers, are vey good and the texts are clearly printed – though a stanza of text has been missed out in the second of the Somervell songs (‘A voice by the cedar tree’), though the song is sung in full. I do, however commend EM Records for the clarity with which the contents of the booklet are presented.

If you are interested in English song, you should certainly investigate this disc

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free