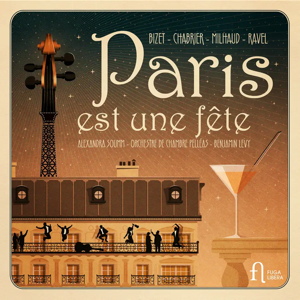

Paris est une fête

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974)

Le bœuf sur le toit, cinema-fantaisie pour violon et orchestra (1919-1921)

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894)

Bourrée fantasque (1891), orch. Thibault Perrine (2007)

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Tzigane, rhapsodie de concert pour violon et orchestra (1924)

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Symphony in C major (1855)

Alexandra Soumm (violin), Orchestre de chamber Pelléas/Benjamin Levy

rec. 2021, Salle Colonne, Paris, France

Fuga Libera FUG813 [66]

Founded 20 years ago, the Pelléas Chamber Orchestra is made of 46 musicians who, if the hyperbolic blurb included in the booklet accompanying this CD is to be taken at face value, seem to be a pretty remarkable bunch. Ever eager to add to the gaiety of nations, I quote from it at a little greater than usual length – though, believe me, I could have included even more in the same vein. “Very much ahead of its time, this dream orchestra [original author’s emphasis] is an assembly of talented friends…, all of whom share a desire to work on an equal level in a musical world that is practically always based on pyramidal hierarchies. Such trust and friendship leaves a deep imprint on the sound and unique dynamic created by this fraternal ensemble… Pelléas is now, more than ever before, an orchestral utopia in which the quality of their nhuman [sic.] relationships, their taste for celebration and for sharing the performance experience and the sensitive links that connect them to each other remain the most precious and the most fragile of objectives”.

Suitably awed and with an appropriate sense of enormous gratitude for the opportunity of hearing this orchestral utopia in action, I slipped its new CD Paris est une fête (“Paris is a party” – see footnote)into the machine…

Le bœuf sur le toit, nowadays one of Milhaud’s most popular works, has undergone some significant changes since it began life in 1919 as a piece for violin and piano. At the time, the composer fancifully suggested that his “merry, unpretentious divertissement” might make an effectively atmospheric accompaniment to one of Charlie Chaplin’s fast-moving slapstick comedy shorts. Instead, however, it was orchestrated the following year to provide the score for an avant-garde surrealist stage show with mime – sometimes described rather loosely as a ballet – put together by Jean Cocteau. With performers recruited from a circus troupe, an iconoclastic scenario that included a policeman decapitated by a ceiling fan, and a glutinously slow manner of dancing that was incongruously at odds with the music’s relentlessly exhilarating Brazilian rhythms, the production was a succès de scandale that put both Le bœuf and its composer on the musical map.

Artistic fashions were, however, constantly changing in the febrile years immediately after the end of the First World War. As the doyen of dance historians Cyril W. Beaumont neatly observed in his magisterial Complete book of ballets [London, 1937], “novelties were acclaimed with rapture by the advance-guard [sic.] just as they were ferociously attacked by the conservative critics. In after years it is sometimes difficult to understand the clamour excited by certain productions, so often is the sensation of to-day [sic.] the commonplace of tomorrow” (op. cit., p. 817). In that jazzy age of ephemeral artistic fads, that was, indeed, to be the very fate suffered by Le bœuf. One might even have thought that Mr Beaumont had had the piece in mind while he was writing, except for the fact that he seems not to have regarded it as a “ballet” at all and so failed to include it in either his Complete book or any of its three supplementary volumes.

Thus, Le bœuf, considered iconoclastic and ground-breaking in the 1920s, had pretty well lost its radical edge by the 1960s. Interestingly, however, that was not only because music itself had moved on. There had also been changes in the way in which the piece itself was perceived. From a brash, raucous accompaniment to the antics of vaudeville clowns, delivered by reduced forces from the modestly-sized orchestra pit of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, it had been transformed, over the years, into a regular repertoire piece for full-sized symphony orchestras, with consequent changes in the style in which it was performed. When, for instance, Antal Doráti recorded the piece with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1965 (Mercury Living Presence 434 335-2), the deployment of a full orchestra reduced the impact of the dissonance and tonal astringency that would have been more apparent in smaller-scale accounts. At the same time, Doráti’s less frenetic, generally slower tempi robbed the piece of its original distinctly manic atmosphere (coming in at 18:35, he was almost four minutes slower than the composer himself had been in 1958 [EMI Classics CDC 7 54604 2]).

The Pelléas Chamber Orchestra now delivers a revisionist account that restores many of the characteristics of Le bœuf’s earliest smaller-scale performances and, in thinning out its orchestral textures, restores much of its original flavour. Taking the piece back to its surreal and musically discombobulated post-First World War roots brings out a hugely enhanced degree of spiciness and piquancy that becomes apparent after just 20 seconds or so with the entry of the very accomplished soloist Alexandra Soumm.

Having listened to her only other recording that’s been reviewed on this website, way back in 2008, Jonathan Woolf thought Ms Soumm “a clearly talented young musician”. A year later, our colleague Simon Thompson attended a live concert in Edinburgh at which he considered her “a real phenomenon… [displaying] astonishing virtuosity and a real sense of showmanship… She took four ovations which were clearly well earned. Definitely one to watch.” If somewhat belatedly, I can only echo their enthusiasm. Ms Soumm brings both sensibility and virtuosity to a performance that, like Milhaud’s score itself, never flags. Her solo violin emphasises the piece’s smooth, almost oily, sinuosity as she glides through phrases punctuated, much more noticeably than before, by discordant harmonies and invigoratingly astringent interjections from all points of the orchestral spectrum. I have always enjoyed Dorati’s classic performance – much more so than the composer’s own – but suspect that in future it will be this intoxicatingly lively new version that I will be taking down from my shelves whenever I fancy a quick burst of Brazilian fiesta cum Parisian fête.

The original version of Chabrier’s Bourrée fantasque was the composer’s final composition for solo piano. Surviving sketches indicate that he himself had planned to orchestrate it but he died before completing the task. The conductor Felix Mottl – an admirer and promoter of Chabrier’s operas – subsequently produced an orchestrated version (as he also did of Chabrier’s Trois valses romantiques) that appeared on concert programmes throughout the 20th century. It has previously been reviewed on these pages in vintage performances by, among others, Alfred Hertz, Charles Munch and, outstandingly, the still underappreciated Paul Paray, while a more modern recording comes from Neeme Järvi. On Christmas Day 2007, however, the Pelléas Chamber Orchestra gave the world premiere performance of a brand new orchestration that it had commissioned from Thibault Perrine. The CD booklet very usefully reproduces part of the autograph score showing Chabrier’s own pretty minimal sketches and, on the facing page, Perrine’s fleshed out version. It also gives us a lengthy paragraph from Perrine himself, in which he explains that enough original Chabrier remains to suggest that the composer’s orchestration would have been lighter and more spare than Mottl’s. Taking that as a starting point, Perrine managed to orchestrate the first third of the piece in accordance, he believed, with the composer’s intentions. He freely concedes that he tackled the final two thirds essentially in the dark apart, though guided by the original piano solo and, he assures us, in “total fidelity to the composer’s spirit, à la manière de Chabrier”.

Just as the Mottl version had suited such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic (Munch) or Detroit Symphony (Paray), Perrine’s slimmed down orchestration is a good match for the Pelléas Chamber Orchestra’s more limited and differently balanced resources – as, indeed, one would only expect, given that it had commissioned the piece. Here Chabrier’s Bourrée fantasque emerges as lighter and more agile, once or twice reminiscent of, say, skittish Mendelssohn, rather than something resembling a late Romantic overture. As such, it fits rather neatly into this disc’s theme of jolly, carefree partying. This is very different from Mottl’s orchestration and I am pleased to have now heard both.

Alexandra Soumm returns to take a prominent and once again distinctive part in Ravel’s concert rhapsody Tzigane. Tzigane’s early performance history somewhat mirrors that of Le bœuf sur le toit in that it too was originally written for violin and piano, yet, within a few months, had been repurposed for violin and orchestra (though, in this case, sans clowns). The primary interest in this particular recording is that it is the first to be based on the newly published Ravel Edition. A detailed explanation of the difficulties faced in attempting to locate and/or recreate definitive Tzigane scores from a wide yet fragmentary range of sources would take up too much space here, so I refer any interested readers to the appropriate page of the Ravel Edition website.

Openings to concertos or concertante works can be tricky. Considerate composers craft substantial orchestral introductions, allowing soloists to work their way psychologically into the musical idiom and to acclimatise themselves to the characteristics of the individual performance well before they play their first note. In like manner, any virtuoso fireworks may be postponed until the soloist has had a chance to warm up a little. Ravel, however, is somewhat mischievous. He locates some of Tzigane’s most difficult technical challenges in the unsupported opening cadenza that takes up a substantial proportion of the whole piece (in this particular performance, that’s more than four minutes of its total time of 10:28). As a result, the soloist needs to be to be absolutely focused and stylistically prepared from the very start. Ms Soumm is certainly that. She impresses even more here than in Le bœuf, playing with a winning combination of purpose and flexibility and making light of all the piece’s considerable technical difficulties. Even after the opening cadenza has been completed, the reduced size of a chamber orchestra accords the solo violin somewhat greater sonic prominence than is sometimes the case and, with strong support from the Pelléas players, this account of Tzigane proves one of the most enjoyable to have come my way in recent years.

You might normally think a symphony something of an odd choice for a CD that’s promoting its contents as party music. Since its rediscovery in the 1930s, however, Bizet’s C major symphony, composed when he was just 17 years of age but neither published nor performed in his lifetime, has delighted audiences thanks to its irrepressible charm and effervescent joie de vivre. As you might expect, past MusicWeb reviewers have varied in their assessments of individual performances. Even so, in a remarkable display of near unanimity, every one of them seems to find it impossible not to respond to what Michael Cookson describes as the piece’s “unalloyed, joyful disposition of a score blanched with summer sun”. Among others, Brian Wilson lauds its “youthful charm”, while Ian Lace focuses on its “exceptionally bountiful outpouring of memorable melodies… [and] fresh out-of-doors appeal” (review) and its “delightful melodic (this work truly brims with good tunes) and sunny [atmosphere]” (review). Our editor-in-chief John Quinn reacts in the same way to the symphony’s “delightful and engaging [qualities]”, while John France’s response to the score is simply one of “pure enjoyment”.

As in most other accounts, the three allegro movements (I. allegro vivo, III. allegro vivace and IV. allegro vivace), each brim-full of exuberant high spirits, go with a real swing. In this recording, though, it is the symphony’s adagio second movement that arguably makes the most distinctive impact, as the Pelléas Chamber Orchestra’s reduced forces deliver a particular degree of refinement and delicacy that immediately and forcefully brings a chamber music performance to mind. In, for instance, both the beautifully crafted opening section where the solo oboist and pizzicato violins introduce the main theme and the subsequent brief fugal episode for strings, one can almost see the players’ furrowed brows and eagle eyes as they concentrate on the score and on their conductor for all that they’re worth. That particular movement comes across with a degree of intensity that I’ve not encountered in any other performance and, for that reason alone, this disc warrants a place on my shelves.

Expressively delivered slow movements aside, we must keep in mind this release’s portmanteau title Paris is a party. If the recent over-long and at times somewhat am-dram opening ceremony of the Olympic Games wasn’t necessarily the best advertisement for a shindig-on-Seine, this new disc offers us the opportunity to explore the music of a different era when, it claims, the City of Light “set the tempo for cosmopolitan and carefree celebrations”. As it clearly demonstrates, Milhaud, Chabrier, Ravel and Bizet certainly knew how to communicate real joy and liveliness in their scores, while Alexandra Soumm, conductor Benjamin Levy and the players of the Pelléas Chamber Orchestra demonstrate an almost tangible degree of fun and enthusiasm in their very well recorded performances. Even if I remain unconvinced by all that over-the-top self-promotion (“this dream orchestra… an orchestral utopia”, indeed!), I can certainly appreciate the fine musicianship that’s on display on this imaginatively compiled and altogether very finely executed new disc.

Rob Maynard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Footnote

Paris est une fête may also be translated as Paris is a feast. The CD’s packaging unfortunately fails to identify which translation English-speakers ought, in this instance, to use. Incidentally, Paris est une fête is also the French-language title of Ernest Hemingway’s A movable feast, a memoir of his life in Paris in the 1920s. After the November 2015 terrorist attack, the book became a best-seller in France, supposedly because its French title epitomised the spirit of the capital city’s defiance in adversity. However, once again the CD’s packaging offers no indication of whether, or how, its title might relate to that particular issue.