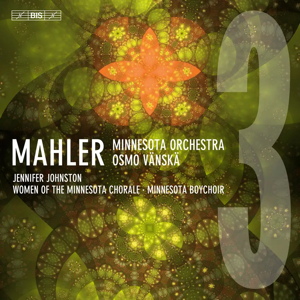

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No 3 in D minor (1895-96)

Jennifer Johnston (mezzo-soprano)

Minnesota Chorale (Ladies’ voices); Minnesota Boychoir

Minnesota Orchestra / Osmo Vänskä

rec. live, 14-18 November, 2022, Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis, USA

Texts & English translations included

BIS BIS-2486 SACD [2 discs: 104]

Only a few months after the release of the Eighth symphony (review), BIS release the final instalment in their Mahler cycle by the Minnesota Orchestra and Osmo Vänskä; sadly, it does not appear that Das Lied von der Erde will be part of this series. I’ve either reviewed or purchased all the previous releases in this cycle and though it has been interpretatively uneven at times, there has been a great deal to admire. Two consistent features of the cycle have been the top-class playing of the Minnesota Orchestra and the outstanding BIS engineering; both of those characteristics are present in spades in this recording of the Third symphony.

It was with the performances of the Eighth symphony in June 2022 that Vänskä brought down the curtain on his long term as music director of the Minnesota Orchestra. The concerts from which this account of the Third derives were given a few months later, in November 2022. I wonder if the original plan had been that BIS’s cycle would culminate with the Eight; Vänskä’s tenure in Minneapolis was subject to a number of disruptions and it may well be that the Third had to be rescheduled. Those disruptions included a lengthy industrial dispute and, of course, the Covid pandemic; nonetheless, Vänskä and his orchestra have a number of significant achievements from their time working together. These have included, on disc alone, cycles of the symphonies of Beethoven and Sibelius; now their Mahler odyssey is also complete.

With this performance of the Third I’m put in mind of the old adage, ‘don’t judge a book by its cover’; in this instance I might advise don’t judge a performance by its opening. I think Vänskä doesn’t quite get the start of Mehler’s Third right. His tempo for the big horn tune is on the broad side, only by a fraction, but here the theme seems to lack a crucial spring in its step. Then, when the slow march begins (1:27), I feel Vänskä is just a fraction too measured. If, by comparison, you turn to Leonard Bernstein’s 1961 recording (review) then I think you’ll find the difference palpable. Bernstein takes the horn theme only fractionally more quickly than Vänskä but the NYPO horn section sounds livelier; in New York it’s a really proud, portentous beginning. Bernstein is also better with the slow march; he conveys more tension. However, on the plus side, Vänskä ensures that the string tremolandi and the upward rushes on the lower strings are terrifically incisive. And when Mahler moves to more delicate, dance-like music (6:05), not only do we hear expertly delivered solos from the first oboe and the concertmaster but also Vänskä adopts an entirely convincing light-footed tempo. I have to caution, though, that shortly thereafter the slow march returns (7:18), this time including the imposing trombone solo. This big, rhetorical solo is splendidly played by R Douglas Wright but Vänskä’s tempo is just a bit too slow and as a result the solo and its accompaniment tends to hang fire. I’ve gone into some detail about these first few minutes because they set the tone for the movement as a whole. I don’t think that Vänskä gets the treatment of that slow march quite right but – and its an important ‘but’ – he gets a lot else absolutely right. I referenced that passage between 6:05 and 7:18; happily, that’s much more representative of the conductor’s overall approach to the movement. In the quicker march episodes, he may not match the swagger that Bernstein offers but even so the rhythms are suitably jaunty and I enjoyed a lot of what I heard. There are two other factors which weigh heavily in Vänskä’s favour. One is the superb playing of the Minnesota Orchestra. They really are on terrific form throughout the symphony, both collectively and individually; in particular, the brass make a marvellous impression, the horns ring out imperiously, the bassoons have a satisfyingly deep tone and the percussion are ideally incisive. The second factor is the BIS recording. I can’t readily recall hearing this symphony in such sonic splendour. The recording has a tremendous dynamic range, a plethora of detail can be heard and the sound is not only impactful but has a fine degree of truthfulness. Those comments about the quality of the playing and of the recorded sound apply not just to the first movement but to the symphony as a whole.

So, despite my reservation about one interpretative aspect of the first movement, overall, it’s an impressive traversal.

The second movement, Tempo di Menuetto, comes across very well. Vänskä leads a performance that is both lively and stylishly detailed. He treats the music affectionately and the results are very likeable. Throughout, the playing is crisp and expertly articulated. This degree of excellence carries over into the third movement. The Scherzando episodes are well pointed and I think Vänskä paces the music astutely and idiomatically. A key feature of the movement is the unashamedly sentimental middle section involving a posthorn solo. The Minnesota player, Manny Laureano, is deservedly credited in the booklet. The instrument that he uses – the Dotzauer Fürst Pless Rotor 18915 valved posthorn in B flat – even merits a photograph in the booklet. The sound is marvellously evocative in this performance. Laureano and his instrument are heard distantly – but clearly – and the effect is magical. Vänskä and his musicians perform this episode beautifully; everyone involved plays with wonderful refinement and delicacy. An aural vision of an innocent, nostalgic past is conjured up until (at 11:18) the little trumpet call jerks us back to the reality of the present day – or, rather, to the present day of Mahler’s time. I’m not sure I’ve heard the posthorn episodes more successfully delivered on any of the (many) recordings of this symphony I’ve previously heard.

Vänskä takes the fourth movement very spaciously. Where most conductors in my experience have taken between about 8:40 and 9:40, Vänskä’s reading takes 10:25. His pacing is similar to Claudio Abbado in his 1982 DG recording with the Vienna Philharmonic and Jessye Norman. To be honest, I feel that both Vänskä and Abbado push the envelope a bit too much in this movement; in both cases, the performance is full of dark atmosphere but the music is stretched almost to its limits and momentum suffers. Vänskä’s soloist is the British mezzo, Jennifer Johnston. She sings very well and with evident feeling; I enjoyed her performance very much. The Minnesota Orchestra delivers their conductor’s vision of the music, investing the music with rich, deep colours. In the fifth movement we hear perky, alert singing from the Minnesota Boychoir while the ladies of the Minnesota Chorale offer fresh tone and rhythmic incisiveness. My sole reservation about the performance comes midway through when we hear music that Mahler would later use in the finale of the Fourth symphony; nicely poised singing by Jennifer Johnston can’t dispel my feeling that Vänskä’s tempo is a fraction too cautious.

Vänskä’s basic speed for the long Adagio finale is suitably broad and spacious. By comparison, Bernstein is significantly slower (Lennie takes 25:09 for the movement, whereas Vänskä brings it in at 23:49). Unsurprisingly, Bernstein invests the music with great emotional feeling – though he doesn’t overplay his hand. During my appraisal of this Vänskä performance I’d done some comparative listening to two other favourite versions, though I haven’t referenced either of them earlier in this review: Jascha Horenstein’s 1970 studio recording (review) and Klaus Tennstedt’s live 1986 performance (review). Horenstein’s way with the finale is rather more direct than Vänskä’s – and even more so when one compares him with Bernstein; Tennstedt’s approach, which I described as “noble and spacious” when I reviewed it, is not dissimilar to Horenstein’s. I wouldn’t be parted with any of those three recordings and I find much to admire in Vänskä’s reading of the finale too. I like the way he achieves the necessary solemnity while maintaining good flow. He’s not as intense as Bernstein, but many listeners will value a slightly more sober approach. Vänskä brings concentration and focus to the music and the results are very rewarding. And there is intensity too, when required – the climaxes at 13:40 and 16:17 are very powerful, yet the emotion is always controlled. Whether you are fully convinced by Vänskä’s approach to the finale or not, I hope no one will be disappointed by the playing. The Minnesota Orchestra, which has been truly excellent throughout the symphony, seems to find an extra gear in the finale. The strings play the opening pages with great finesse; in fact, I’d rank the sheer quality of their playing even more highly than that of the orchestras in the three other versions I’ve cited; the refinement of the Minnesota strings is memorable. The last few minutes of this performance are wonderful. From 17:57 the brass chorale is played with golden tone, paving the way for a glorious final peroration by the orchestra. In the closing four minutes or so the sheer amplitude of the BIS recording means that the whole orchestra sounds wonderfully sonorous. Though BIS don’t include any applause – as is their wont on a live recording – I bet the audience, commendably silent throughout the performance, raised the roof when the final chord had died away.

So, it’s a wrap. That’s the end of Osmo Vänskä’s Mahler cycle from Minneapolis. I expect that by now most collectors will have made up their minds about the cycle. If you like high-octane intensity in Mahler, as dispensed by the likes of Bernstein, Solti and Tennstedt, then Vänskä is probably not for you. His approach is more objective, some might say cool. I’ve found the cycle to be occasionally variable in terms of the interpretations, and although I’ve never been seriously disappointed, I have to admit that I’ve not felt excited sufficiently often. Not once, though, have I had any cause to question the quality of either the playing of the Minnesota Orchestra or the BIS engineering. Both have been top-drawer and that’s certainly true of this final instalment in the cycle.

I’ve expressed one or two reservations about Osmo Vänskä’s interpretation of the Third symphony but for the most part I’ve enjoyed and admired his reading of this huge score. He has been admirably served by his singers and by the first-class orchestra which he led for 19 years. I listened to the stereo layer of this hybrid SACD. The recording was produced by Robert Suff, who I think has produced the entire series, and the engineering was in the hands of Marion Schwebel and Jay Perlman; they’ve done a fantastic job; the recording has presence, impact and all the detail you could desire..

If you’ve been collecting Vänskä’s cycle, you’ll certainly want to complete the set with this fine account of the Third. If you’ve not so far encountered this conductor in Mahler, or if you’ve only experienced a couple of the symphonies in his hands, it may be worth noting that BIS have just released the entire cycle of ten symphonies in a box of 11 SACDs at a very advantageous price. My colleague, Roy Westbrook has now comprehensively reviewed that box set.

Previous review: Ralph Moore (July 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.