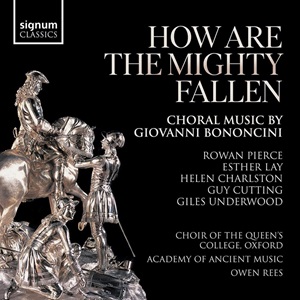

Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747)

How are the mighty fallen – choral music

Ave maris stella

Te Deum

Laudate pueri

When Saul was King

Rowan Pierce (soprano), Esther Lay (mezzo-soprano), Helen Charlston (contralto), Guy Cutting (tenor), Giles Underwood (bass)

Choir of the Queen’s College, Oxford; Academy of Ancient Music/Owen Rees

rec. 2021, Church of St Michael and All Angels, Oxford, UK

Texts and translations included

Reviewed as a 24/96 download with PDF booklet from Premier

Signum Classics SIGCD905 [72]

The Academy of Ancient Music, one of Britain’s main baroque orchestras, has devoted a recording to music performed by its 18th-century namesake. It was founded in 1726 as the Academy of Vocal Music, with the aim of performing sacred music and madrigals written during the 16th and 17th centuries. The founders and members were a mixture of professional musicians and aristocratic amateurs. In the course of time, the interest in contemporary music increased at the cost of ‘ancient music’. In 1731, their name was changed to Academy of Ancient Music.

Several composers of repute were connected to it, among them Johann Christoph (John Christopher) Pepusch, Francesco Geminiani, Giovanni Battista Sammartini and Nicola Haym. Others were the castrato Senesino and the violinist Giovanni Stefano Carbonelli. The present disc includes music by another Italian, Giovanni Bononcini, who settled in England in 1720. He had been engaged by the Earl of Burlington with the aim of composing operas for the Royal Academy of Music, an association of noblemen founded the year before in order to promote Italian opera. For two seasons his operas met with great acclaim, but in 1722 he was not re-engaged. This was largely due to his Catholic faith and the fact that he became involved in the conflict between the Jacobite movement – supporters of the Stuarts, who had been driven out of power by William of Orange – and the monarchy. Bononcini was again engaged for the season 1723/24, but that met with stiff opposition, which made Bononcini leave for France in the summer of 1724. After the summer, he returned to London. He became connected with the Duchess of Marlborough, for whom he performed his own music at her private concerts. At the same time, he became involved in the activities of the Academy of Vocal Music. This also resulted in his downfall, as in 1731 a madrigal by Antonio Lotti was performed, which some years earlier had been performed as well, but then as a work by Bononcini. The composer and his friend Maurice Green, who had introduced the piece to the Academy, were discredited, and Bononcini left for France.

The present disc opens with a short work, a setting of the Marian antiphon Ave maris stella. It is a piece for solo voices, choir, strings and basso continuo. In the opening verse, the upper voices recite the plainchant melody. The text is through-composed and not divided into separate verses. Owen Rees, in his liner-notes, does not mention the year of composing; it may not be known. One wonders whether such a piece, which is part of the Catholic liturgy, was performed by the Academy of Ancient Music.

That is different with the second work, a large-scale setting of the Te Deum. This text was closely associated with monarchies and affairs of the state. Settings of this text were often performed before monarchs at special and happy occasions, such as a birthday or the birth of a successor, and to celebrate a military victory or the signing of a peace treaty. The latter was the case with Handel’s Utrecht Te Deum, performed to celebrate the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. The occasion for which Bononcini composed this work is not known. Rees states that “[the] use of Latin in Bononcini’s work signals that it could only have been used as a concert piece in England.” Bononcini later reworked it for a performance in Vienna, as a commission from the Empress Maria Theresa. The difference with Handel’s Utrecht Te Deum not only concerns the language, but also the fact that the bulk of Bononcini’s setting is given to solo voices – very much under the influence of opera. Whereas in Handel’s setting, most sections are choral. There are some very expressive sections, thanks to an imaginative and text-inspired use of harmony, and in some sections Bononcini gives an obbligato part to the cello, his own instrument. In the choruses, the strings are joined by trumpets. This work also attests to the composer’s command of counterpoint.

Laudate pueri is one of the Vesper psalms; Bononcini had written several settings during his stay in England. Again, one may wonder where this work has been performed. It was certainly not intended for the Anglican liturgy, which was entirely in English. Owen Rees writes that this psalm was frequently set by Catholic composers; this may well indicate that Bononcini’s setting was also written for the Catholic Church. The work is divided into eight sections, alternately scored for solo voice(s) and choir. The influence of opera is noticeable in the fifth section, ‘Suscitans a terra’, for soprano solo. The opening of the doxology is for three voices, an illustration of the Trinity.

The programme closes fittingly with a piece of funeral music. When Saul was King was written in 1722 for the funeral of John Churchill, first Duke of Marlborough, who was considered a national hero because of his involvement in several battles during the War of the Spanish Succession. According to the newspapers, it was performed by more than seventy singers and players. Rees mentions that it may have been the first orchestral funeral anthem performed in England. Notable is the opening with its dotted rhythms, modelled after the French overture. The phrase “How are the mighty fallen” is set in an upbeat manner, as here the “mighty” are the Duke’s enemies. The atmosphere turns sour in the ensuing accompanied recitative: ‘How doth the city solitary sit’, followed by the aria ‘All the night she weepeth sore’, both for alto solo. The work ends softly on the text “Howl, O ye fir-trees; for the cedar is fall’n”.

One may assume that all these pieces are appearing here on disc for the first time. Bononcini is a composer whose music is not that often performed and recorded, and what is available on disc are mostly his Italian secular music and his instrumental works. This disc is very interesting in that it shows that his activities in England went beyond opera. These four pieces are all of excellent quality, and one would hope that they are going to be published; except the funeral anthem, Owen Rees is responsible for the editions which were the basis for this recording.

This release deserves an unequivocal welcome, not only because of its historical importance and the quality of the music, but also because of the level of the performances. In the 1720s the upper parts were sung by boys; the Choir of the Queen’s College Oxford is a mixed choir, but the sopranos sound very youthful, and that makes it a very good alternative to a real boys’ choir (which would have been preferable). The choral singing is outstanding. The contributions of the soloists are generally very good and enjoyable as well. Only Rowan Pierce now and then uses a bit too much vibrato, for instance in Laudate pueri. Among the soloists, Helen Charlston stands out. As one may expect, the Academy of Ancient Music delivers fine performances; I am especially happy with the differentiated treatment of dynamics.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site