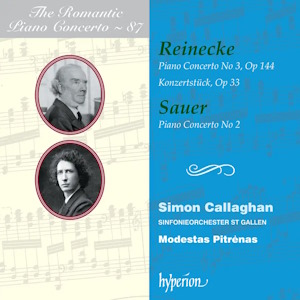

Carl Reinecke (1824-1910)

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Op. 144 (1877)

Konzertstück Op. 33 (published by 1855)

Emil von Sauer (1862-1942)

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 254 (1901)

Simon Callaghan (piano)

Sinfonieorchester St Gallen/Modestas Pitrenas

rec. 2023, Tonhalle St Gallen, Switzerland,

The Romantic Piano Concerto Vol. 87

Hyperion CDA68429 [82]

Hyperion’s Romantic Piano Concerto series, which has now reached Volume 87, must surely stand as one of the great achievements of classical recording. The label’s usual standards of presentation and recorded excellence are all present here, as Simon Callaghan and the St Gallen Orchestra complete their recordings of the Reinecke Piano Concertos.

Carl Reinecke is one of those composers whose name crops up in the biographies of other composers. This is not because he was musically relatively inactive, quite the reverse in fact, as his catalogue, stretching to Op 288, illustrates. He was a pianist, violinist, composer, conductor and teacher; he was revered in his lifetime as the conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and arespected teacher at the Leipzig Conservatory.

Given the concerto’s date of composition it sounds musically very conservative, and even if we remove from comparison those composers most associated with the Weimar school, we can compare it with the first concerto of Brahms which had been around for some twenty years, and the famous one by Grieg (a pupil of Reinecke) which had been published nearly ten years before this, Reinecke’s penultimate piano concerto. Given these comparisons and others that could easily be made, I was surprised to read in the booklet, that it was regarded by his contemporaries as the most significant piano concerto of its day; however, it is notable that Reinecke himself was quite sanguine about the shelf-life of his music: “I will not indulge in the misleading hope that my works are set to endure for very long”.

I must say that I found nothing about this concerto that would lead me to want to contradict his opinion. It is a long time since I listened to a piano concerto that goes nowhere in thirty-five minutes, but this one fits that description pretty well. The whole work is devoid of thematic contrast, and proceeds on its Mendelssohnian way, with much pianistic passagework that rarely ceases. The orchestral accompaniment is plain to the point of being uninteresting, despite the excellent playing of the St Gallen orchestra. Even the slow movement is devoid of a decent tune, and the allegro vivace e grazioso last movement is at times quite perky, if not gracious. I am sure that Simon Callaghan has done his considerable best with it, but it provokes a yawn in me. If you have responded well to the earlier Hyperion disc of Reinecke’s First, Second and Fourth concertos (CDA68339) then you might find this piece appealing.

It is followed on the CD by the Konzertstück Op. 33, which is a single-movement piece with three sections corresponding to the usual movements. I find it to be a more interesting work than the concerto, starting as it does with an unusual lengthy crescendo for the orchestra, terminated by the grandioso entrance of the piano. The soloist plays around with the first notes of the crescendo theme, and the music becomes quite catchy in a lilting manner. The central section is really rather nice, a song without words, and I suspect that it is based on the popular Scottish song Annie Laurie (whose tune was composed in 1834-5 by Alicia Scott). The five-minute last part starts with a solemn hymn-like tune decorated with piano figurations which is succeeded by a rather impassioned episode that leads into the rousing finale. I think that it is a much better work than the concerto, having much more interesting and well contrasted episodes for the listener to appreciate.

The Second Piano Concerto of Emil von Sauer is more interesting to me, given the splendid Hyperion recording of his first concerto, reviewed here. Sauer himself was a virtuoso on the European and American stages. He considered that the main influence on him was Nicholas Rubinstein, but spent a few weeks with Franz Liszt towards the end of the grand old man’s life, and subsequently claimed that the aged and ailing Liszt had had no significant influence on him. A photographs of Sauer in the early 1900’s show him with untamed dark brown wavy hair, and it croses my mind that he might have been copying Paderewski, whose long golden locks were famous. In 1917 he was raised to the Austrian nobility which entitled him to use the ‘von’ before his surname. In fact, Liszt had been similarly ennobled in 1871, but unlike von Sauer, did not bother to call himself von Liszt.

Sauer’s Second concerto presents the listener with an opening that promises exotic eastern influence, as a seductive oboe begins the proceedings, immediately followed by a short solo passage for piano. Unfortunately, Sauer doesn’t build on the orientalism, and that initial promise doesn’t evolve much, as the music only rarely and discreetly returns explicitly to opening oriental musing. He is rather profligate with his melodic ideas, so when a duet between piano and trumpet appears, to my ears it has nothing in common with the opening oboe melody. There is a short section where a childish-sounding tune interplays with brief violin phrases, and he is not afraid of unleashing virtuoso fire power, either by the soloist or by the orchestra, to break up the musings. The overall impression is of a movement that tries to be virtuoso in nature, but cannot resist several diversions into slow solemnity, playful tinkling, orchestral solos, pianistic surges and so on. Although I enjoyed this first movement, I think that I will have to indulge in much more repeated listening before my aural memory can piece things together.

The scherzo-like second movement consists of arguments between soloist and accompaniment when a dance like tune appears shared between piano and orchestra. This is succeeded by a more richly scored version with the piano playing a vivacissimo part. Then we are suddenly into a melting tune for a few bars, then back to the vivacissimo, until about a minute before the end things relax for the orchestra to do a bit of swooning, directly into the third movement.

Here we are into the heart of the concerto. The rather fabulous slow movement opens with a hyper-romantic piano solo and is immediately succeeded by the orchestra accompanying the piano. This is music to which I can lie back and let it wash over me, as it slowly develops to a grand crescendo at the half-way point, where after quieting, the whole ensemble, including piano, indulges in a grand peroration and then another on top of that. Finally, the piano is left solo, quietly playing ornaments as the orchestra creeps in to softly support it, and then the movement closes quietly. The whole CD is worth it for this one eight-minute movement.

To be frank, I feel a bit let down by the last movement. The first theme is jaunty in contrast to the previous movement, after which a new romantic theme is introduced which is played in brief counterpoint with the jaunty theme. Then the orchestra has the stage to itself; briefly the music becomes heated before the piano reappears. Material is tossed back and forth with quotes from earlier on in the concerto; then the piano begins a summing up with a short cadenza which leads into the final run-in with the orchestra in tow.

In summary, I should say that the work is very entertaining, and the slow movement is splendid in every respect.

This 87th volume in the Romantic Piano Concerto series has been produced to Hyperion’s usual immaculate and imaginative level, with great pianism, splendid orchestra playing and interesting, if not wholly successful representatives of the genre. The documentation in the booklet is detailed, in English, French and German, and is well up to Hyperion’s usual exalted standard.

Jim Westhead

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free