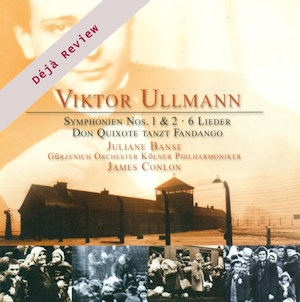

Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2003 and the recording is still available.

Viktor Ullmann (1898-1944)

Symphony No. 2 in D Major (1944, reconstructed by Bernhard Wulff from the short score of the seventh piano sonata)

Sechs Lieder Op. 17 (1937), for soprano and chamber ensemble on poems by Albert Steffen

Don Quixote Tanzt Fandango (1944)

Overture, reconstructed from the short score by Bernhard Wulff

Symphony No. 1, “On My Youth” (1943, reconstructed by Bernhard Wulff from the short score of the fifth piano sonata)

Juliane Banse (soprano)

Gürzenich-Orchester Kölner Philharmoniker/James Conlon

rec. 2002, Studio Stolberger Strasse, Kölner Philharmonie, Germany

Capriccio 67017 [62]

The story of Viktor Ullmann is becoming more familiar to us. From the mid-nineties, up until today, we have witnessed increased interest in his music, with his best known work, “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” (The Emperor of Atlantis) being staged on both sides of the Atlantic, specifically by conductor James Conlon, in the U.S.

Viktor Ullmann was born in Bohemia, in Teschen (now Poland). After spending his youth in Vienna, he joined the army, returning from war in 1916. He enrolled in Arnold Schoenberg’s composition class, studying with him for a little over eight months. Ullmann then moved to Prague where he worked as an assistant to Alexander von Zemlinsky at the German theatre. It was under Zemlinsky’s direction that his style as a composer crystallized: a fascinating middle ground between Schoenberg and Zemlinsky, with a very free tonal language, making use of polytonality, and yes, sometimes atonality. The result is extremely original, appealing to both modernists and traditionalists alike. From this period, the major work seems to be the “Seven Songs for Orchestra“, Op. 7, now unfortunately lost.

In 1931, after conducting in Aussig and Zurich, Ullmann decided to take over an anthroposophical (beliefs he adopted while in Zurich) book shop in Stuttgart. He effectively stopped composing during this period. The rise of the Third Reich forced him to move back to Prague in 1933. He then resumed composition. The most notable work of this period is the opera “Der Sturz des Antichrist“, a fascinatingly Wagnerian drama, based on an anthroposophical text. Musically, it is an extremely dense work, where influences of Mahler, Zemlinsky, Schoenberg and even Debussy collide to form the now recognizable Ullmann style.

The long hand of the Third Reich finally caught up with Ullmann in Prague. After being denied visas by Switzerland and the U.S.A., Ullmann had no choice but to return to Prague and endure the conditions imposed by the Nazi occupation. He was eventually interned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Ullmann left all of his scores behind, choosing instead, to take blank music paper.

Paradoxically, this marked the beginning of Ullmann’s most prolific period. He composed most of his surviving output there, in addition to conducting, writing and teaching. Along with composers Pavel Haas and Hans Krasa, he worked under the mantle of the Freizeitgestaltung (Administration for free time activities), designed to showcase Theresienstadt as a model ghetto and proof of Hitler’s “good” treatment of Jewish interns.

It was in Theresienstadt where Ullmann composed the opera “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” Op. 49, based on a text by fellow inmate, painter and poet Peter Kien. The Emperor portrayed in the opera, a bellicose leader with no regard to the life of his subjects, is in fact a very thinly disguised Adolf Hitler. Death goes on strike with disastrous consequences, agreeing to go back to work only after the emperor agrees to be his first victim. The opera actually went into rehearsal, but it was never staged. Camp authorities realized the meaning of the production, cancelling the premiere days before it was supposed to happen. Viktor Ullmann was transferred to Auschwitz, where he perished in the gas chambers within two days of arrival. Before being sent to the death camp, he was able to entrust all of his scores to a friend in the camp. They were miraculously preserved, so, in fact, all we have of Viktor Ullmann’s works is his Theresienstadt output, while most of what he wrote before is now lost.

James Conlon, whose Zemlinsky advocacy resulted in a series of very worthy releases for EMI, is now turning his attention to Ullmann, whose music he found while researching the life and works of Zemlinsky. He has already conducted a staging of Kaiser in the U.S.A. and now has turned his attention to Ullmann’s orchestral output.

All the works in this release were originally presented as either piano or short scores. However, the Piano Sonatas 5 and 7 had many indications of orchestration ideas, which suggest that they started out as Symphonies No. 1 and 2. Ullmann decided to use the smaller form, since a symphony had little chance of being properly performed at Theresienstadt. In my opinion, most of Symphonies No. 1 and 2 are bit too sparsely orchestrated by Bernhard Wulff for my taste. Antichrist, Kaiser and other works suggest a much denser orchestral style. In fact, while this is not indicated in the external info, the booklet tells us that the Six Songs were originally scored for piano and orchestrated by composer Geert van Keulen for chamber ensemble. This is, in my opinion a more successful orchestration, more consistent with Ullmann’s style.

The first work presented in the CD is the Symphony No. 2. The first movement, marked Allegro, is a very airy, Haydn-esque piece played with confidence by the Kölner Philharmoniker. The instrumentation includes unusual support from the harpsichord, a choice no doubt influenced by Ullmann’s use of it in Kaiser. In this movement, the strings are recessed in the soundstage, which makes the woodwinds sound very prominent, to good effect though, since they play a big part in the development. Conlon provides a good, unrushed pace, resisting the temptation of overdoing the Classicist connection.

The second movement is a Mahlerian march. Again, the sound engineer made the choice of somewhat recessing the strings. Still, they sound rich and powerful, a characteristic of this orchestra also evident in Conlon’s Zemlinsky EMI recordings. The cello has a couple of prominent parts that are handled with confidence by the soloist. The movement finishes with a mysterious, Brucknerian fanfare with support from the harpsichord.

The third movement is a very beautiful adagio, where the Schoenberg influences come to the fore. The piece is very tonally ambiguous. This time, the strings take centre stage, now properly placed in the soundstage. This Mahlerian adagio picks up the pace in the middle section, very much in the style of Webern’s Passacaglia. Conlon does a great job with the orchestral balances, not letting the powerful and clear brass overwhelm the very important lines assigned to the woodwinds and solo violin. Close to the end of the movement, the piece becomes atonal, not only affirming the Schoenbergian ideas, but giving the finale an unsettling feeling, no doubt mirroring the terror and uncertainty of life in the ghetto. The key to the successful interpretation of this type of piece is to let the richness of the music emerge, without letting it drag, otherwise it becomes just a wall of string sound. Conlon does it very well.

The fourth movement is full of Ländler-type rhythms, with very forward brass. This is a rhythmically difficult piece, executed with aplomb and precision by the orchestra.

The final movement, “Variations on a Jewish theme” is the jewel of the symphony. After stating the main theme, a set of extremely lyrical and beautiful variations are presented. The poignancy of the melodies is sometimes overwhelming, causing the mind to remember where this music was composed and the conditions under which human beings, including the composer had to live. After that, a scherzo is introduced, with Conlon handling the transition well. This big and affirmative ending suggests the existence of hope, as a source of strength against the horrors of ghetto life.

The Six Songs for soprano and chamber ensemble are, in my opinion, better orchestrated from the piano originals. The orchestration is dense, more consistent with the style shown by Ullmann in Antichrist, Kaiser and the Theresienstadt string quartets. The style could be described as oscillating between Berg’s Seven Early Songs and the Altenberg Lieder. Songs 1 and 2 are lyrical, introspective pieces, while 3 and 4 are more Mahlerian. They are very well handled by Banse, who has a very secure top and a richly expressive voice.

The overture “Don Quixote tanzt Fandango” is, like the songs, orchestrated in a rich style, very reminiscent of the Gurrelieder. The piece starts slowly, with prominent parts for solo violin. These are played proficiently, although somewhat coldly. Then, as the name suggests, it turns into a highly dramatic dance piece, with great support from a percussion section that includes castanets. Here, Conlon relishes the dance element, accentuating the rhythms and maintaining a very appropriate pace. The result is a very enjoyable performance.

The last work on the CD is the Symphony No.1, after the Sonata for piano No. 5. This suffers from the same sparse orchestration as the Symphony No. 2. The first movement, an Allegro, has a Viennese waltz mood and is played with gusto by the orchestra. This is light music with a very serious streak. The next movement, the Nocturne Andante, is slow and lyrical, with Conlon, once again, doing a great job of balancing the strings and woodwind, the main elements in the piece. The Toccatina is an extremely short (49 seconds), minuet type piece that is mostly brass, percussion and woodwinds. The Serenade is reminiscent of the Nachtmusik II in Mahler’s 7th, with similarly prominent parts for harp. The last movement, Finale fugato, is a lively march that sounds as if it might have been what Mahler would have produced if he had tried to imitate Alban Berg. Again, the woodwinds and brass of the Philharmoniker shine in this piece.

In general, James Conlon does a wonderful job with the music. He does not try to force it into the avant-garde. Instead he shows Ullmann in his true colours: a late-romantic as greatly influenced by the works of the Second Viennese School as he was by Zemlinsky and Mahler.

The recording is typical of Capriccio: clear, spacious, clean and bright, a bit lacking in the low-end, although this is not a big problem. Notes and texts are provided in German, English and French.

In conclusion, a great recording; my disagreement with the orchestration choices in the two symphonies notwithstanding. This is in fact a good introduction to Ullmann, showing us several facets of his work.

Victor Martell

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free