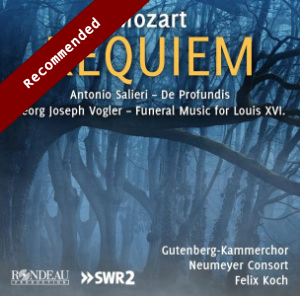

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Requiem in D minor, KV 626 (1791)

Georg Josef Vogler (1749-1814)

Funeral Music for Louis XVI

Antonio Salieri (1750-1825)

De profundis

Chisa Tanigaki (soprano); Rebekka Stolz (alto); Fabian Kelly (tenor); Christian Wagner (bass)

Gutenberg-Kammerchor

Neumeyer Consort/Felix Koch

rec. 2019, Sängerhalle, Saulheim, Rheinland-Palatinate, Germany

First recordings: Salieri, Vogler

Latin text with German and English translations

RONDEAU ROP6211 [59]

This new recording of Mozart’s unfinished liturgical masterpiece presents two particular claims for our attention: a new completion of the Amen fugue in the Lacrimosa by Birger Petersen, Professor of Music Theory at the Mainz School of Music and world premiere recordings of music by two of Mozart’s contemporaries. Before you get too excited by those novelties, I should point out that the completion of the fugue in the Lacrimosa, which runs out after only fourteen bars, amounts to only a couple of minutes of music at most, and the two world premiere pieces are eight and four minutes respectively. Otherwise, the Requiem is as Mozart left it and completed by his pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr; as such, its desirability might still be measured against the best of the myriad recordings of the Requiem in the catalogue – but given that the Neumeyer Consort is a specialist baroque instrument band, we must also take into account any taste for “period” sensibilities and practice.

I am familiar with a dozen recordings of the work but my experience of HIP versions is limited, as I know only Christoph Spering’s 2001 account, issued with fascinating fragments of the original, uncompleted manuscript. I have always thought it rather fine, which, I hope, suggests that I am by no means opposed to the “authentic” treatment.

However, I approached this recording with trepidation, having just before reviewed a Verdi Requiem newly issued on the Rondeau label which has the unfortunate distinction of being the worst recording I have ever encountered. I am not in the habit or business of trashing commercial releases and was hoping to be able to be kinder here.

I am pleased to report that first impressions were very good – although I immediately felt that the orchestra were rather predominating over the choir, so balances could at first be better, but that soon improved. I was also at first a little disconcerted by the manner in which the choir, evidently following instructions – emphasise the first note and syllable of phrases, but that adds a certain percussive impact and they are fleet enough in the runs of the Kyrie eleison. The Dies irae is fast and furious – rather exciting – and that leaning on the first beat adds extra urgency. Diction is crisp – for example, the hard c’s in “cuncta stricte” are nicely articulated and although at only 29 members the choral forces are relatively small, compared with “traditional” performances they do not lack weight, vigour or intensity. The men display great energy and attack, then the women show poised control in their alternating phrases in the opening of the Confutatis. The three-quarter-time new music in the Lacrimosa fits seamlessly. The drive of the “Quam olim Abrahae” is infectious; the choir sounds as if it is living and thoroughly enjoying this wonderful music. Some might find the Agnus Dei a little brisk but it is virtually identical in duration to Spering’s, even though his recording is considerably larger-scale. In fact, by comparison, with the advantage of twenty years’ hindsight I would say that this new recording makes Spering’s sound rather cumbersome, as if he hasn’t quite squared the circle regarding the mutually exclusive merits of the two approaches. His Kyrie, for example, now sounds rather lugubrious.

I was able to breathe a sigh of relief upon the entry of the soprano, Japanese singer Chisa Tanigaki, who has a round, pure, fluty tone of boyish quality until she injects vibrato. The bass does not have a major voice but he is musical and tonally even; the same may be said for the tenor and the alto is equally pleasing on the ear; they make a well-blended team – nobody is throaty, squeezed or breathy.

Perhaps I am a musical illiterate but I have never been able to hear the supposed disjuncture between Mozart’s intentions and Süssmayr’s elaborations; I am of the camp which believes that the “scraps of paper” Constanze gave him were of much greater help than has subsequently been surmised; anyway, I have always enjoyed the completion and this recording certainly evinces no stylistic chasm between the master’s and pupil’s respective inspiration. The concluding, cumulative “Cum sanctis tuis” attains a truly monumental quality to cap a totally committed and professional account.

For a traditional reading, I find great merit in recordings by Barenboim, Colin Davis, Karajan, Kempe, Kertesz, Marriner, Solti, Walter – and, above all, Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, way back in 1968, on EMI – but for a refreshing take on this music in which details, subtleties and nuances are revealed, this smaller-scale performance has much to commend it and I confess that against expectation I thoroughly enjoy it.

The Vogler work has an oddly quaint quality and is reminiscent of a combination of Mozart’s Masonic music and his wind compositions such as the Gran Partita – rather attractive, in fact, albeit very brief. The Salieri piece is clearly somewhat stilted conventional and old-fashioned compared with Mozart’s inventiveness, but interesting.

The booklet contains a transcription in German and English of a conversation about the programme between the conductor and Prof Petersen.

Ralph Moore

Availability: Rondeau