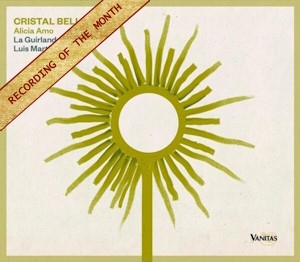

Cristal Bello: Musicas a lo divino en la España y el México virreinal del siglo XVIII.

Alicia Amo (soprano)

La Guirlande/Luis Martinez (transverse flute)

rec. 2020, Epila, Spain

Sung texts, and translations in English, French and German included

Vanitas VA-16 [68]

There is an interesting historical ‘narrative’ underlying this attractive disc of music from eighteenth-century Spain, involving the influence of Italian (particularly Neapolitan) music in Spain and its colonies. One circumstance which should not be forgotten is that Spain had a dominant position, politically speaking, vis-à-vis Naples from the early years of the sixteenth century until the eighteenth century and cultural connections naturally developed alongside the political links. Sometimes such connections and patterns of influence can be identified and exemplified in the lives of individual musicians.

One vivid example is provided by the life and work of the violinist and composer Ignacio Jerusalem y Stella (1707-1769). He was born at Lecce, on the eastern coast of the Kingdom of Naples. In 1732 he left Italy for Spain and was employed at a theatre in Cadiz. Ten years later he was amongst a group of musicians hired to work in Mexico City; he seems initially to have worked in the theatre once more, but from 1746 he was composing sacred music for use in the city’s cathedral and he was successively appointed acting-master of the chapel (1749) and Master of the Choir School, a post he held for the rest of his life. As Antoni Pons Segui observes (as translated by Pablo Fitzgerald) in his booklet essay, “under Jerusalem’s charge, various sets of sacred music composed by the directors of music of the three Royal Chapels in Madrid – José de Torres, José de Nebra, José de San Juan or José Mir y Llusá – were acquired in Madrid for their use in the Mexican cathedral”. (See Javier Marin-Lopez and Drew Edward Davies, Ignacio Jerusalem (1707-1769): Cronología biográfica y lista de obras / Biographical Timeline and List of Works (Madrid: Dairea Ediciones, 2019). Ignacio Jerusalem y Stella is represented on this disc by the aria ‘Cristal bello’, scored for soprano, strings and continuo, with an obbligato role for the transverse flute, as well as by a set of verses in the second tone, i.e. instrumental alternatives. These instrumental verses were designed to replace, on occasion, to some of the verses making up a liturgical text which were normally sung. These examples are taken from a collection of instrumental verses by the Neapolitan composer preserved in the archive of the cathedral of Mexico City and are enough to confirm the competence of Ignacio Jerusalem y Stella as a composer though, by their nature, too brief and relatively simple in purpose, to provide any evidence that he was more than that. Cristal Bello makes a stronger case for Jerusalem y Stella, being a sophisticated piece of work steeped in the musical idioms of his native country.

Several other composers who had developed their skills in Naples also went on to work in Spain and to disseminate the influence of Neapolitan musical models. They included Francesco Corradini (c.1700-post 1749), Giovann Battista Mele (1701-post 1752) and Franco Corselli (1705-1778). Corradini was probably the most important of these figures. Although he seems to have been born in Venice, he began his musical career in Naples during the first half of the 1720s, composing operas as well as at least one oratorio, Il glorioso S. Giuseppe sposo della beata Vergine. By 1728 he was in Spain, as maestro di capilla to Luis Reggio Branciforte y Colonna, prince of Campoflorido , Captain General of the kingdom of Valencia. During his relatively short spell in Valencia, Corradini and his music must have been known to the Valencian Francisco Hernández Illana (c. 1700-1780) who was elected maestro di capilla of that city’s Colegio del Patriarca in 1728; Illana’s delightful cantata Erizada la noche (recorded here) is full of quasi-Neapolitan characteristics (notably in the decidedly ‘operatic’ storm which it incorporates) and is well worth hearing – I would like to hear more of Hernández Illana’s music. In 1729 Illana became maestro di capilla at the Cathedral in Burgos, though he doesn’t seem to have had a very good relationship with the authorities of that cathedral. This may be reflected in the fact that the archives in Burgos contain only a small number of his works. The entry on the composer in the Spanish version of Wikipedia, suggests that there are more works preserved in the cathedral archives of Astorga, Segovia, Segorbe and Valencia, as well as the royal monastery associated with El Escorial.

The story of Jerusalem y Stella involves the composer making two lengthy journeys, from southern Italy to Spain and from Spain to Mexico., and also the importation of scores from Spain to Mexico. A more famous violinist, one of the most highly regarded virtuosi of his age, and composer, Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695-1764). Though Locatelli established a very considerable reputation in northern Europe, giving well-received concerts in such cities as, amongst others, Munich, Berlin, Kassel and Amsterdam (in which city he lived for several years), he seems never to have travelled to Spain, let alone to its colonies. His music certainly found it way there, however – the booklet notes by Antonio Pons Segul refer to a “manuscript copy of the 12 sonatas for flute and bass. Op. 2 by Locatelli […], preserved in the National Anthropological and History Museum of Mexico, dated ‘México y Marzo 10 de 1759’”.

The influence of Italian (and particularly Neapolitan) composers was also furthered by the frequency with which Spanish potentates commissioned new works from Italian composers who chose to stay in their native lands. One such case was that of Leonardo Leo (1694-1724), amongst the most important Neapolitan composers of the day, who played a significant role – along with composers such as Francesco Durante (1684-1755) and Leonardo Vinci (c.1690-1730) in developing the city’s stile moderno – and from whom the Spanish court commissioned a number of works. Through these diverse influences, Spanish sacred music was changed, elaborately polyphonic music gradually being succeeded by simpler, more directly expressive music, music to which terms like stile moderno, galant and rococo have variously been applied. The opera seria of Naples was a clear shaping force in this change, “with its lyrical and cantabile melodies and its relatively transparent textures” (Antoni Pons Segui”. The more rigid ‘rules’ of the older style were gradually relaxed or sidestepped. One might say – at the cost of historical over-simplification – that the absorption of Italian / Neapolitan influences created a Spanish estilo moderno.

Born at Valls in Catalonia, the career of Jaime Casellas (1690-1764) illustrates another route by which Italian influences reached Spain and how Spanish and Italian forms could be juxtaposed within a single work. From the age of six Casellas was a choirboy at the Basilica of Santa Maria del Mar. This brought him under the influence of the Basilica’s maestro di capilla Luis Serra, who had studied with Francesco Durante in Naples and thus became a channel of Neapolitan influence on Spanish music. Casellas’ youth in Barcelona also coincided with some of the years spent in the city by Archduke Charles of Habsburg who brought with him other musical influences from Italy. Casellas went on to teach music in Granollers and the monastery of San Juan de la Abaderas (both in Catalonia) before, in 1716, succeeding his old master Serra as maestro di capilla at Santa Maria del Mar. He remained in that post until 1734/5, when he was appointed maestro di capilla of Toledo’s cathedral. Casellas’ Immenso amor, though designated a tono on its score, is less purely Spanish than that traditional Spanish term for a song might imply. It is, in effect, a sacred cantata in five sections: Aria (Largo) – Recitado – Coplas (Largo) – Recitado – Aria (Allegro). The word copla refers to a traditional Spanish form of verse and song and the third section of Casselas’ Immenso amor respects some of that form’s conventions. The opening and closing sections of the cantata, on the other hand, are da capo ‘Italian’ arias. The presence of both forms within a single work might serve as a symbol of the unified streams of Spanish and Italian idioms in the music of this place and time. The closing aria of Immenso amor (‘¿Cómo, como en contente?’) is one of the highlights of this disc and suggests that Jaime Casellas ought to be better-known than he is. Soprano Alicia Amo is at her best in the performance of this moving aria.

One of the more familiar names amongst the Spanish composers on this disc is that of José de Nebra (1702-1768). He offers an interesting study in how the Italian influence was creatively assimilated in Spain. He was born into a thoroughly musical family. At the time of his birth his father was organist at the Cathedral in Cuenca, about a hundred miles east of Madrid. My limited experience of Cuenca consists of a single daytrip from Madrid. What I remember of the city is its dramatic situation, almost surrounded by three gorges; the glorious gothic and mudejar interiors of the cathedral and the presence of works by El Greco, Gerard David and others in the city’s museums. Listening to a range of works by José de Nebra, it is clear that he was at home in both Spanish and Neapolitan idioms and was often happy to conjoin the two. The story of his career is illuminating in this regard. His father, José Antonio Nebra (1672-1748) was his first teacher and José the younger also became an organist, as did his two brothers; by 1719 he was in Madrid, in the employ of an aristocratic family. In 1724 he was appointed organist at the Royal Chapel in Madrid, as well as at the city’s Convent of the Descalzas Reales. In the first half of the 1730s, several Italian musicians were appointed to the Spanish court (as mentioned previously). In some respects their appointments briefly overshadowed de Nebra, but the opportunity to learn from them proved a more important factor in his development as a composer. In 1734 a fire destroyed much of the music in the collection of the Royal Chapel and de Nebra was among those commissioned to write new music; he wrote some 19 masses amongst a larger body of sacred music. He seems also to have suggested the purchase of music by composers such as Leonardo Leo and Alessandro Scarlatti, both very significant figures in the Neapolitan tradition.

Particularly ‘Neapolitan’ music by de Nebra can be heard (and enjoyed) in, for example, the Italianate arias in his zarzuela, Iphigenia en Tracie (1747) or sacred cantatas such as Alienta fervorosa and Que contrario, Señor. On this disc he is represented by a striking harpsichord sonata, very much in the manner of Domenico Scarlatti, played with impressive panache by Joan Boronat. Listening more than once to this sonata I was prompted to search my shelves for a notebook in which, some years ago, I made some notes on Scarlatti’s sonatas. The passage I was half-remembering comes from a piece on Scarlatti’s sonatas, The mercurial master of Madrid by Robert White, published in The Guardian, July 20th 2007: “They fascinate by drawing substantially on the character and chord patterns of the songs and dances of Spain and Portugal, kept respectable within elegant framing gestures from Italy”. The same might be said of this sonata by de Nebra although he, of course, arrived at this fusion from the opposite starting point, i.e. as a Spanish composer who learned about Italian forms rather than (like Scarlatti) as an Italian-born composer who assimilated Spanish musical elements. I would be delighted to hear more of de Nebra’s sonatas (assuming them to be of he same high standard as this example) played by Joan Boronat. Given that Domenico Scarlatti was at the Spanish court from late in 1733, it is probably safe to assume that de Ne Nebra would have had direct access to Scarlatti’s work and, perhaps, to the composer himself.

The disc closes with an impressive work by an Italian-influenced Spanish composer who seems to have been seriously neglected – Juan Martín Ramos (1709-1789). He appears to have spent his entire musical career in Salamanca, though he was born in Corrales del Vino, some fifty miles south of that famous university city. He was a chorister in Salamanca cathedral from around 1721 and three years later began to study the organ under the tuition of the accomplished organist-composer Francés Iribarren (1659-1767), then cathedral organist in Salamanca. As a composer, Iribarren was open to Italian and French influences, perhaps because of his own early studies with José de Torres (c.1670-1738) at the Royal Chapel in Madrid, who did much to introduce such models to the world of Spanish music. Indeed, in an ideal world, this disc might have found room for some of de Torres’ work – perhaps one of his excellent cantatas for the Blessed Sacrament, such as Amoroso Señor. That Juan Martín Ramos was certainly familiar, directly or indirectly, with the ‘new’ Italianate manner can be heard here in his impressive cantata Sigueme, pastor. Cantada a los Santos Reyes con violines y flauta. It consists of a ‘Recitado con instrumento’, followed by a particularly fine aria. Given that its subject is the Magi, it was presumably written for use at Epiphany. The music depicts, with some subtlety the journey of the Magi at both physical and spiritual levels.

La Guirlande is an outstanding period-instrument ensemble, founded by Luis Martinez during his time at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. The ensemble specialises in 18th and 19th century music, with a particular fondness for works in which the flute plays an important role. La Guirlande has played at numerous music festivals within and beyond Spain. Luis Martinez, here playing a copy by Rudolf Tutz of Innsbruck of a transverse flute of around 1730 made by Jean-Hyacinth Rottenburgh of Brussels, shows himself to be a fluent, sensitive and highly accomplished artist. I was also very favourably impressed by the violinists Lathika Vithanaga and Aliza Vicente. Harpsichordist Joan Boronat shows himself to be intelligent and skilful as part of the continuo section throughout (in which cellist Ester Domingo also impresses), and is a splendid soloist in the Sonata by José de Nebra. Soprano Alicia Amo has an attractive voice, though occasionally she seems to me to employ rather more vibrato than is fully appropriate for this music. This, however, is a very minor blemish in an excellent recording.

Glyn Pursglove

Availability: Europadisc Classical

Contents

Ignacio Jerusalem y Stella (1707-1769)

Cristal bello. Aria de flauta a solo con violones y bajo al Santisimo

José de Nebra (1702-1768)

Sonata de 8o tono*

Jaime Casellas (1690-1764)

Immenso amor. Ono a solo con flauta al Santisimo*Ignacio Jerusalem y Stella

Versos de Segundo tono*

Francisco Hernández Illana (c. 1700-1780)

Erizada la noche. Cantada al Nacimento con violones*

Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695-1764)

Sonata No. 6, Op.2 in G minor for transverse flute and continuo (1732)

Juan Martín Ramos (1709-1789)

Sigueme, pastor. Sigueme, pastor. Cantada a los Santos Reyes con violon es y flauta obligado*

*World premiere recordings

Performers

Lathika Vithanage (violin 1), Aliza Vicente (violin 2), Ester Domingo (violoncello), Joan Boronat (harpsichord), Pablo Fitzgerald (archlute, baroque guitar), Silvia Jiménez (double bass)