Ernest Bloch (1880-1959)

Schelomo (1916)

Max Bruch (1838-1920)

Kol Nidrei (1881)

Ernö Dohnányi (1877-1960)

Konzertstück in D major for cello and orchestra (1904)

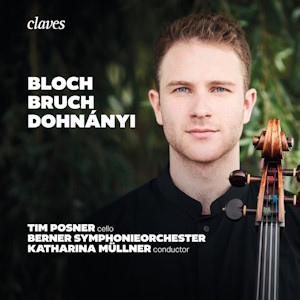

Tim Posner (cello)

Berner Symphonieorchester/Katharina Müllner

rec. 2023, Diakonis-Kirche, Bern, Switzerland

Claves CD3079 [57]

Tim Posner (born 1995) is the Principal Cello of the Amsterdam Sinfonietta and one third of the Teyber String Trio. He won the Thierry Scherz Prize at Gstaad in 2023, as did the violist of the Teyber Trio, Timothy Ridout, in 2019. The reward of recording a disc for Swiss label Claves with the Berner Symphonieorchester is the outcome from that prize. In choosing his programme, it was Bloch’s Schelomo that first leapt to mind – Posner had always wished to play it. That suggests that invitations to play it with a large symphony orchestra do not often drop into the inbox of a young cellist. Do orchestras consider that there might be fine, if neglected, concertante pieces for cello and orchestra beyond the Dvořák, Elgar, and first Shostakovich concertos? Perhaps that prize budget will permit Claves to send a copy of this CD to some orchestral managers, who will thereby discover both fine repertoire and a fine artist who plays it.

Schelomo was the last work Ernest Bloch, Swiss composer of Jewish heritage, completed before he emigrated to America in 1916. Part of his “Jewish cycle“, it was first played in New York in 1917, alongside another of the cycle, the Israel Symphony, also a premiere. Schelomo, subtitled an Hebraic Rhapsody for Cello and Orchestra, was intended to be a vocal work. Then Bloch heard cellist Alexandre Barjansky, and admired the vocal quality that he drew from his instrument.

“Schelomo” is Hebrew for Solomon, and the cello gives voice to King Solomon’s utterances. It is a superb work, one of Bloch’s very best. There is an arresting opening. The solo cello’s playing of a moving lament is ripely expressive, and its sound is well caught throughout its range. The balance is a little close perhaps, but this helps the effect without neglecting the orchestral presence. The majestic third theme, an upward leap and despairing descent, is supremely passionate in the hands of the soloist and (from 7:15) of the orchestral strings. The folk-based material of the central section is calmer emotionally but with a little more lively rhythm. After a powerful restatement by the orchestra (19:00), there is a quiet envoi from the cello. The work is called a Rhapsody, and indeed there are what sound like rhapsodic elements. Posner and the orchestra manage to have it both ways – spontaneous yet structured, a tribute to the insights and skill of conductor Katharina Müllner.

In 1878-1880, Max Bruch led a choir in Berlin. It had a number of Jewish members, including the Chief Cantor of the Synagogue, who introduced him to traditional Hebrew melodies. Bruch, a Protestant, wrote he “felt deeply the beauty of these melodies”. They included the Kol Nidrei, which begins the service on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Bruch’s Kol Nidrei for cello and orchestra is subtitled Adagio on Hebrew Melodies for Violoncello and Orchestra. It begins and ends with the solo cello’s setting of the Kol Nidrei. For the second part, Bruch found a melody in a collection by the Englishman Isaac Nathan. Byron created poetic texts for the collection. For this melody, he deployed the opening of Psalm 137, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea we wept, when we remembered Zion”. His sung poetic version opens “Oh! Weep for those that wept by Babel’s stream.”

The ten-minute Adagio is a work of concentrated dedication. Posner and Müllner find the right tempo, maintained throughout, to reflect that. From the outset, there is a mood of solemn introspection, the sighing of the Kol Nidrei theme ideally suited to solo cello, and well matched by the lower strings of the orchestra when they duet (or perhaps dispute) with the soloist (2:37). The second part begins with harp chords (5:10) and a lift to the major mode for the “Oh! Weep…” theme. Soloist and orchestra at times sound as if they are colleagues playing chamber music.

Ernö Dohnányi’s father was an excellent amateur cellist, which may account for the immediate appeal of his idiomatic writing for the instrument here. The one-movement Konzertstück has several sections, integrated effectively into each other. The Allegro non troppo beginning suggests both a first theme and its development. There ensues an intensely lyrical Adagio (7:47). The cello then yields to a faster purely orchestral passage, before returning (14:45) with the opening theme, passionately taken up by the orchestra. A brief cadenza (18:48) brings in the final passage of cello and orchestra ruminations.

Perhaps neither Tim Posner, nor the Berner Symphonieorchester, nor Katharina Müllner had been very familiar with this piece, but they all sound as if they have played it often, and with affection. At twenty-five minutes, it is the longest piece on the disc. If I was not quite persuaded its material is strong enough to sustain that length for a one-movement “concert piece”, I was glad of the chance to hear it, especially as a foil to the more directly engaging better known companion pieces. (I wonder if a Swiss link, and Honegger’s fine Cello Concerto, was considered.)

The three works each have other recordings. Consider two discs on Hyperion. Natalie Clein plays the Bloch and Bruch pieces, and Bloch’s two other cello works (review). Volume 1 of the Romantic Cello Concerto series, with Alban Gerhardt as the soloist, includes Dohnányi’s Konzertstück and pieces by Enescu and D’Albert(review). But I suspect this issue might be a unique programme, and its main purpose is to announce its soloist. Comparisons are less meaningful when each performance here is good, to say the least.

The recording is good, while it slightly favours the cello in the balance. (Those who ask for a “concert hall balance” on disc like this have not spent much time listening live to cello concertos in a large hall.) The notes, far from extensive, say something about Dohnányi the composer but nothing about his composition. They are useful for the Bruch and Bloch pieces.

Roy Westbrook

Previously reviewed by Dominy Clements (March 10, 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free