Déjà Review: this review was first published in January 2003 and the recording is still available.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Concerto for Piano, Trumpet and Strings in C minor, op. 35 (1933)

Piano Concerto No 2 in F, op. 102 (1957)

24 Preludes for Piano, op. 34 (1932-33)

Oleg Marshev (piano)

Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra/Hannu Lintu

rec. 2002, Konserthuset, Helsingborg, Sweden

Danacord DACOCD601 [77]

It must have been knocking on for forty years ago that I read a review of a recording of Mahler’s First Symphony penned by the late, great Deryck Cooke. With so many recordings of the work already in the catalogue, he argued that the only possible justification for bringing out yet another was to produce an outright winner. What followed in that review could be summarised in four words: “ – and this is it.” That’s my opening gambit done for a Burton, so how then do I start this review?

Well, it will have to be “Rather more prosaically,” but stick around – it won’t stay that way for long! The prosaic fact is that, before I say anything else, I must “declare an interest”. It’s nothing to write home about, really, just that having written the booklet note I can’t comment on its quality. Other reviewers will perhaps fill you in.

The experience did teach me a fair bit about the company, though; not so much facts and figures, but more about their entire attitude and approach to making records. In nature’s realm, it’s generally the case that the smaller the brood, the more care the parent takes of each individual offspring. Something similar might be said of companies. Vast, pan-global industries churn out CDs like frog-spawn, their instincts geared to survival of the species rather than individual progeny. Danacord, as a small company with a rate of production (or should that be “reproduction”?) rather more akin to that of the Giant Panda, by comparison lavishes bags of tender love and care upon each offspring. Our expectation, that we should therefore find issues more thoughtfully conceived and of a consistently higher individual standard, tends to be confirmed by a quick trawl through their extant Musicweb reviews.

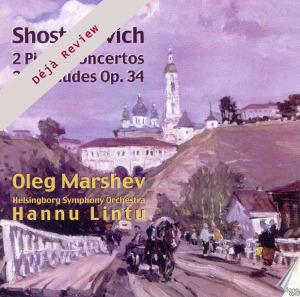

Anyone who has admired the Danacord presentation of the Rachmaninov Piano Concertos set will equally admire this one. The art-work (see illustration) is based on a colourful and atmospheric painting by Alexy Lieberov. This is reproduced both on the inside of the back cover and on the CD itself, so that when the disc is placed in the transparent tray the continuity of the scene is preserved. Need I say that to benefit from this neat effect you do have to line it up accurately?! The booklet is tidily laid out, including all pertinent details except, oddly, any identification of the subject of the painting. As well as the usual photographs of the soloist and conductor, there are a couple of the young Shostakovich and on the back cover a shot of the HSO players involved in the recording. This last is truly splendid, because it’s not the usual “ochestra at work with faces all fuzzy and anonymous” sort of thing, but a proper group photograph in which every individual can clearly be seen as a friendly face. I rather like that.

Although alternative versions of Shostakovich’s two piano concertos have never burdened the CD catalogue quite as much as the Mahler First, we are still fairly spoilt for choice. Hence, I do wonder: is the only possible justification for bringing out yet another still to produce an outright winner? Exercising marginally more caution than Deryck Cooke, I’ll add, “- and is this it?” Ever responsive to such promptings, my subconscious mind appends a marginally less cautious, “Very probably,” so now I’ll have to justify it!

With a combined running time of a little over 40 minutes, the two piano concertos were a convenient pairing on LP. However, because of its greater popularity, recordings of the Second were often paired with something else. As dim and distant memory serves me, there was a stubby-fingered but loveable Bernstein LP which had the Ravel Concerto in G on the flip side. On CD though, 40 minutes is a bit mean, so (if you’re lucky) there’s a “make-weight”. With up to 35 minutes to play with, companies have a golden opportunity to exercise a bit of imaginative programming.

For example, Dmitri Alexeev’s excellent Classics for Pleasure recording included something of a rarity, The Unforgettable Year 1919. That’s all very nice of them, but his short (and I mean short!) concertante piece, with its origins in a film score and its rather nice (though I’d hesitate to say “unforgettable”) tune, would have fitted rather more comfortably on CfP’s disc of Warsaw Concerto (et al.). Turning to the recording that currently graces my collection, EMI and Cristina Ortiz give you, at about three minutes, the fantastically brief Three Fantastic Dances for solo piano. Now, that would be mean indeed, were it not that the two-CD set also includes Berglund’s brilliant Sixth and Eleventh symphonies!

Yet, neither of these examples shows any real imagination. Without wading through the catalogue with a fine-tooth comb I couldn’t swear to this (so please correct me if I’m wrong), but I think that no-one has ever coupled the the piano concertos with the Twenty-Four Preludes Op. 34. If I risk discounting a few juvenilia (like the Aphorisms, a smaller batch of Preludes, and those Three Fantastic Dances), I think I can fairly say that the Op. 34 Preludes are the very platform on which Shostakovich set out his considerable pianistic stall. Not only are they a pivotal work, but also they are intimately connected to the concertos. Now, this adds up to not justa bit of imaginative programming, but a bit of truly brilliant programming.

It feels like I’ve heard more performances of these concertos than I’ve had hot dinners, and in both cases few of them were “turkeys”! However, aware of the tricks the memory (especially my memory!) can play, I’m going to limit any comparisons I do make to the Ortiz/Berglund recording.

Even the mere mention of the name of the pianist on this CD will have many seasoned MusicWebbers scrambling eagerly along that well-worn bee-line to their preferred record suppliers. This wouldn’t surprise me, because Oleg Marshev is a thoroughly remarkable phenomenon, who has already been documented in some detail in other MusicWeb reviews of his work.. In these days, when every young pianistic pretender is dubbed “virtuoso” almost before he or she is even out of nappies (or daipers, if you prefer), Marshev is not a virtuoso. Why not? Because he is, first and foremost, a musician. Don’t get me wrong: he can mix it with the best of them when it comes to dazzling digital dexterity, but it isn’t top of his list of priorities. Having sampled quite a few of his recordings, including both concertos and solo works, the overriding impression I get is of a “Barbirolli of the keyboard” ‑ the quality that shines through, again and again, is unashamed love for the music he is playing. At each and every turn, he seems to be asking not “What can I do to show myself to the best advantage?” but “What should I do to show the music to the best advantage?” I’m not claiming that Marshev is alone in this, any more than Barbirolli was, but like JB he is one of a rare breed whose affections radiate, even through the impersonal filter of a recording.

Although Shostakovich’s two piano concertos have very distinct (and distinctive) characters, they do have some things in common. For example, both are very carefree works (here I’m hoping that nobody takes the “doom-laden” centre of the First even remotely seriously!), and both are unusually scored for relatively small forces ‑ the First for strings with obbligato trumpet, while the Second is for a “classical” orchestra, without trumpets, trombones or tuba but including an “obbligato” part for snare drum. This is significant: Shostakovich, even more than the Ravel of the G major Concerto, nips in the bud any possibility of neo-Romantic heavyweight fisticuffs between the modern concert grand and the modern symphony orchestra. (in this light, could perhaps that pianistic ruck in the middle of the First be seen as parody, or even sarcasm?). By paring down his orchestra, Shostakovich instead points the piano in the direction of agile articulation, clearing the decks for lithe athleticism in the First, “Haydn-esque” humour in the Second, and sublimely slender, saccharine-tinged romances in both.

Another consequence is that on this CD we hear only portions of the Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra. Like the WDRSO on the Brilliant Classics set of the symphonies, the HSO is a provincial orchestra, similarly and gratifyingly endowed with endearing qualities, notably a richly communicative, down-to-earth character and palpable enthusiasm for the music they’re playing. The HSO does of course lack that intercontinental gloss that these days seems to be de rigeur but, as it happens, “gloss” is something these concertos can well do without. On the other hand, the HSO is not short on the sort of inciseveness that can cut blond hair lengthways, which, equally “as it happens”, is something on which these concertos positively thrive.

Having said that, you won’t be surprised when I say that the body of strings is on the small side. This might well be a budgetary imposition, but it actually sounds far more like a shrewd artistic strategy, as Hannu Lintu harnesses their slimline strengths into a marriage of chamber-style delicacy and balletic muscularity. In the faster music of the First Concerto, they are so nimble and fleet of foot that, unlike other more plushly upholstered string bands, they skitter over Shostakovich’s pellucid textures like pebbles skimmed across a frozen lake. In the slower music, and especially the “bar ballad” of the second movement, their lightness of tone and keenness of intonation are melded into sweet and soulful intimacy. class=Section2>

The trumpeter is Jan Karlsson, who has stepped forward from the ranks of the orchestra.. I’m told that he declined to have even a brief note about himself put in the booklet, basically on the grounds that he is simply a loyal member of the orchestra doing his bit when called on, and he doesn’t want any sort of special treatment at the expense of his colleagues. Well, I’m sure his colleagues will understand, because he’s going to get some from me! His playing, like his loyalty, is almost beyond praise (I’m only really saying “almost” because nobody’s absolutely “perfect”). His execution is nigh-on flawless, dispatching his part with both flair and a good deal of wit, admirably complementing Marshev’s flying fingers. At the other extreme, namely near the end of the slow movement, he finds smoky langour in his muted crooning of the main theme.

Even the sound he makes has a distinctive quality. Many years ago, when I was a student, I knew this other student who was a cornettist in a brass band, and (in common with all British brass band players) a real fanatic. In all innocence, I wondered why it was that brass bands included cornets but not trumpets. He gave me a withering look, and retorted, “Because cornets can ‘trumpet’ when they need to, but trumpets can’t ‘cornet’!” The relationship of this tale to the price of eggs is that since then I’ve often thought that Shostakovich’s trumpet part might have been better given to a cornet, especially when it comes to the rumbustious allusion to Der Liebe Augustine, a tune as ripe for a bit of “cornetting” as you’re likely to encounter on the concert platform. The point is that this trumpeter comes nearer to “cornetting” than any trumpeter I’ve ever heard ‑ rarely has the piano’s scrunching comment seemed more like a hearty elbow in the ribs! Impressed? You will be.

It’s strange how you can go along for years and fail to see something that’s staring you in the face. Listening to this recording I was taken aback to realise that apart from the pianist the only clear solo line in the Second Concerto belongs to the snare-drummer! True, a bassoon opens the proceedings (this bassoonist would make a sprightly grandfather in Peter and the Wolf), but this is its one and only solo, and it lasts scarcely a couple of bars. Considering Shostakovich’s fondness for woodwind solos, I somehow don’t think this was an oversight. The effect, of course, is to focus attention more sharply on the busy piano part, so it probably has something to do with paternal pride: the work was conceived as a birthday present for his son, Maxim, who was at that time a budding pianist.

Having been “robbed” of the opportunity to shine individually, the HSO winds are utterly unfazed and busily apply themselves to shining collectively. In a work where I had, over the years, become accustomed to the winds sounding vaguely monochromatic, largely differentiated only into “dark” and “bright”, Hannu Lintu coaxes from his willing troops a fascinating diversity of textures that my ears simply hadn’t noticed before. Of course, it helps to have no more than a svelt string body to penetrate, but then that’s all part of the “shrewd strategy”, isn’t it?

Right, add the HSO, Hannu Lintu, and Oleg Marshev together, and what do you get? Well, the sparks fly, but not quite as you might expect. My faithful old Ortiz/Berglund recording, which used to sound so vivacious, by comparison now sounds dull. Ortiz herslef is articulate and alive, but her piano sounds ponderous. The Bournemouth SO string section, itself hardly the most populous, does come across as a bit opaque. With equally “one size fits all” winds I suspect matters might not have been helped by the recording, which lacks a sparkling edge. On the other hand, when Joanna MacGregor played the Second with the Slaithwaite Philharmonic under Adrian Smith a year or two back, the slow movement was meltingly delicate, and in the outer movements sparks flew in all directions! It was superbly played, but the problem was that it was just a bit too “hell-for-leather”, rather too much “Beethoven” and nowhere near enough “Haydn”.

Marshev’s piano is very much “up front”, but is nevertheless beautifully balanced against the small orchestral forces. The quality of the piano sound makes an important contribution. It’s hard to describe, but (inevitably) I’ll try. Imagine a very clean sound, having a full dynamic range but with scarcely a trace of the “velour” resonance that tends to flesh out the sound of a powerful modern piano. Better, imagine the transparency of the “authentic” early-Romantic piano married to the purity of tone and dynamic stability of a thoroughly modern instrument. Under Marshev’s fingers it can slice like a rapier, it can “glitter and be gay”, it can drip dewdrops of sound, and it can bash out a thunderous bassline without becoming merely “thunderous”.

The upshot of all this is a pair of performances of remarkable clarity and insight. Where required, there’s plenty of “welly”, but there is hardly a moment passes in which you don’t feel the shade of Haydn hovering within the music. To my mind, they don’t put a toe (never mind a whole foot!) wrong in the First Concerto, where Shostakovich’s musical imagination is positively running riot. In the first movement, Marshev is only marginally faster overall than Ortiz. However, his moderato is a bit slower, making his playing of the vivace episodes not only relatively quicker but also, by virtue of the crystalline ensemble and scintillating fingerwork, positively tingling (the prefix “spine” is omitted entirely on purpose!). The slow movements of both concertos are a lot slower than Ortiz (in both cases, nearly a minute longer than her average of seven minutes). Taking all the time in the world is fine in the First, where the movement is marked “Lento”, but might be questioned in the Second’s “Andante”. However, Marshev and Company come up trumps: by letting in some air they give themselves an important bit of elbow-room in which to wax poetic, and then proceed to take full advantage of it.

Contrariwise, Marshev takes the First’s tiny third movement (marked “Moderato”) quicker than Ortiz. By not lingering, he points up the parallel with the famous bridge passage in the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, similarly placed and having a similar function. Performance-wise, the finale picks up where the first movement left off, the lazy, thigh-slapping heft of that tune for “cornetting” trumpet made, by heightened contrast, into a leery joke in the worst possible taste, which is exactly how it should be!

Turning to the Second, I encountered my one brief moment of doubt. After the relaxed and aimiable tune, shouldn’t the central episode of the first subject have a bit more verve? Afew moments of reflection yield the answer “no”, because the two episodes are “in tempo” ‑ like the “horse and carriage” of the old song, they go together. Of course, a few pianists of a particularly virtuoso inclination are tempted into hoicking up the tempo. Both Marshev and Ortiz, to their credit, don’t. Ortiz, at a faster basic tempo, gains on the “verve”, whilst Marshev wins on the “aimiable”. Interestingly enough, the second time I played Marshev’s performance of the movement, it already sounded “right”, which says much for his perception of the tempo ‑ the “verve” lies not in the tempo as such, but in the “attitude”. The climax of this movement is superb. The build-up at the end of the development digs deep into the style of Rachmaninov in barn-storming mood, with the rampant piano surmounting the orchestra. Yet, when the music spills over into the reprise on that characteristic unison tutti, Marshev’s piano is exactly where it should be, embedded in the body of the orchestra, reinforcing the massive effect.

Lintu and Marshev match Berglund and Ortiz almost to the second in the finale, but the story remains the same: the Danacord artists find much more sheer fun and “punch” in what is effectively a slapstick “boxing match” between the two incongruent themes.

Overall, the real joy of these recordings is not simply Marshev’s thoughtful and articulate readings, it is not simply the Helsingborg orchestra’s clean-limbed playing, steered with wit and zest by Hannu Lintu, nor is it simply the admirable clarity of the recording, which fails miserably to sound the least bit “dry” as a result! No, it is all these together, a production which as a whole conspires with considerable success to exceed the sum of its parts. There’s not much comes my way that brings with it such unalloyed pleasure.

I’ll bet you’re thinking that I’ve forgotten about the Preludes! At over 33 minutes, they are a very substantial complement to the concertos. They have little in common with their magisterial predecessors, the Preludes of Chopin and Debussy, largely (I would guess) because they were written for a very different purpose. Ranging in length from a maximum of no more than 2’31 to a mere, minuscule 0’31, you could fairly call them “pithy”. Some of them are a bit like Webern, though mostly only inasmuch as Shostakovich seems to have the same knack of making music that plays tricks with the listener’s sense of time.

This performance provokes a palpable sense of peering over the shoulder of the composer in his workshop, trying his hand at all the different styles and techniques he’s encountered, sifting and searching for the common thread of his own individual voice amongst it all. It’s a feeling that is heightened by the numerous occasions a movement sets off purposefully, only to peter out in apparently aimless doodling! Marshev’s playing seems to go right to the heart of this imagined scenario, drawing out rather than trying to conceal this vision of a composer “losing the thread of his argument”, of turning over his ideas and wondering what he might possibly do with them.

But they’re not all like that, by any means. Some of them jump up and whack your face with a smart idea, then just as smartly they are gone, leaving you with a smarting face. Again true to the scenario, a few (like the famous No. 15) emerge as perfectly formed little gems. Part of the wonder of discovering these Preludes lies in second-guessing what happens to each idea. How often were my expectations confounded, one way of the other!

I’ve no other recording to hand, so I can make no direct comparisons, but it’s nonetheless clear that Marshev brings to these solo pieces every bit as much consideration as he brought to the concertos. Tempi and tempo relationships always feel right, everything feels comfortable (which is not the same as “predictable”!), ebbing and flowing, inflaming and soothing entirely in sympathy with the musical lines. Moreover, each vignette’s character and style are captured to a “T”. I must confess a particular fondness for Marshev’s way with the bibulous little dances, which are made to lurch with delicious giddiness from one precarious harmonic pose to the next. Putting it in a nutshell, Shostakovich wrote and, it seems, Marshev plays what Shostakovich wrote.

The recording engineers, Lennart Dehn and Stephan Flock, have done a cracking good job. My one bone of contention ‑ and, note, this is simply a matter of personal taste! ‑ is that in the stereophonic image of the concert platform the piano occupies a rather large space. This is a distortion of perspective apparent only to hardened headphone users like myself. Through loudspeakers you are hardly likely to even notice it, never mind find it a problem. However, I must stress that this is distinct from the dynamical balance between the piano and orchestra. Although the piano is right at the front, which given the balance of forces is exactly where it should be, you can still hear everything that the orchestra is getting up to. The sound quality matches the piano and orchestra in its cleanliness and clarity, yet nobody is going to find any real trace of dessication in either the direct or ambient signals. Nigh on exemplary, I’d call it.

This issue has one very serious flaw that I feel duty bound to report. Simply, it may be too good. In this production Danacord have set themselves a very high standard: now they are going to have to work their socks off to maintain it, because as sure as eggs is eggs folk are going to expect lots more of the same!

By anybody’s standards, that adds up to something of a Cooke-style “outright winner”. I must admit, it’s set me wondering to what extent any reviewer who has “declared an interest” might thereby be influenced. Hum! Of two things I have no doubt. One is that you will, quite rightly, be wondering the self-same thing. The other is that I believe, hand on heart, that if I’d been less than

enthusiastic about the CD, the combination of integrity and “interest” would have prevented me from submitting a review. I have simply commented as I found, so shoot me down in flames if you can. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this thought: remember what it is that constitutes “the proof of the pudding”!

Paul Serotsky

Help us financially by purchasing from