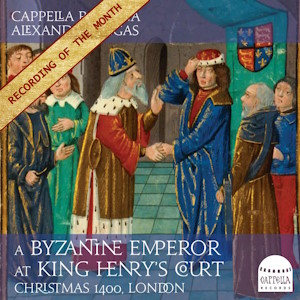

A Byzantine Emperor at King Henry’s Court

Cappella Romana/Alexander Lingas

rec. 2022, The Madeleine Parish, Portland, USA

Texts and translations included

Reviewed as a stereo 16/44 download

Cappella Records CR427 [71]

The title of the disc under review may make the reader raise his eyebrows. What kind of business had a Byzantine emperor at the court of an English monarch? This episode in English history may well be little-known, and it is nice that Alexander Lingas, in his liner-notes, explains the background to a programme of liturgical music from two very different traditions.

The Byzantine emperor the title refers to was Manuel II Palaiologos (1350-1425). When he was crowned in 1392, Byzantium was in a state of deep crisis, due to the constant pressure from the Ottoman empire. In 1373, the Ottoman Turks had managed to make Manuel’s father their vassal. When he became emperor, Manuel tried to regain independence, and looked for support from Christian rulers in Europe. At the end of the 1390s, he appealed to the monarchs of France and England and to the pope in Rome for aid. Both monarchies reacted positively. However, Manuel realised that he had to go to the two countries in person to make sure that the support would be substantial. In the spring of 1400, he settled in Paris, where he would stay two years. Shortly after his arrival, he started to look for the chance to visit the English King Henry IV, the son of John of Gaunt (1340-1399). Henry had usurped the throne of England from his nephew, Richard II. in October 1399. Manuel crossed the Channel and finally met Henry on 21 December at Eltham Palace, where the two monarchs celebrated Christmas together – and that is the starting point of the programme that Lingas has recorded here with his Cappella Romana.

When monarchs travelled elsewhere, they never did so without their chapel in their retinue. It is known that the celebrations were magnificent and expensive, but no details about the music performed have been preserved, therefore the programme of this disc cannot be a reconstruction. “From the English chroniclers’ report that the emperor’s clerics performed daily services; however, from the state of schism that existed between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, we may conclude that each monarch would have attended festal worship celebrated according to their respective rites. Consequently, most of the contents of their services may be reconstructed from other textual and musical sources”, Lingas states. He does not specifically say so, but from this phrasing we may conclude that the two monarchs did not participate in each other’s religious celebrations. The programme is constructed in such a way that the chants from the two traditions alternate, but apparently they were not performed that way. The confrontation of the two traditions is something only the listener to this disc can experience.

Traditional chant was at the heart of both the English and the Byzantine liturgical repertoire, but the way it was treated was different. Both elaborated on what had been handed down from tradition. In England, the so-called ‘Sarum’ chants were extended by counterpoint, which was either written out or improvised. The most frequent form of the latter is known as faburden (faux-bourdon): a method for producing three-part polyphony by adding voices moving above and below the chant. One could call this a ‘vertical’ extension. In the Byzantine liturgical music the elaboration was ‘horizontal’, through the technique of kalophōnía: “recomposing, often extending and generally making them more virtuosic through the widening of vocal ranges and the insertion of melismas, passages on strings of non-semantic vocables such as ‘anané’ and ‘terirém’, and textual troping.”

The programme is divided into three sections; each comprises elements from the services on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and the Second Vespers on Christmas Evening. The first three chants are for Christmas Eve. It opens with ‘Sarum’ chant: Iudaea et Hierusalem is a responsory at Vespers or the Vigil of the Nativity of the Lord. Next are two pieces from the Byzantine tradition. The Christmas ceremonies opened with the chanting of the daily prayers in the presence of the emperor, and at the climax of the Ninth Hour (comparable with the None in the Western tradition) acclamations were inserted wishing the imperial family long life. There were other moments during the Christmas Eve celebrations that further acclamations for the emperor and his family were sung. Two such pieces are included here. The first opens with the words “Christ who crowned you is born”, which connects the birth of Christ with the rule of the emperor. In the second we meet a typical feature of Byzantine liturgical music. It is known as the kalophonic style. “Its first word immediately dissolves into abstract music sung to sequences of non-semantic syllables (vocables) known variously as ēchē´mata (a word used also to denote the vocal intonations sung to establish the mode (ēchos) of a chant) or teretísmata (a term recalling the buzzing of insects).” We meet this feature in several other chants in the course of the programme.

The second chapter, devoted to music from the Services of Christmas Day, opens again with a piece from the English tradition. Ovet mundus letabundus is a four-part motet from a 15th-century collection with liturgical music from around 1400. “Let the world rejoice gladly, drumming out a song, for the fructifying, spotless child is born of a virgin”. The next piece is of comparable content: “All things are filled with joy today, for Christ is born from the Virgin”. It is a so-called pentekostárion – a hymn attached to Psalm 50 (51), one of the seven penitential psalms. Then we get the ‘Sarum’ responsory O magnum mysterium, whose text has been set numerous times by composers of the Renaissance. It is followed by a Kanon, referring to a category of hymns with several stanzas, originally written to accompany the verses of the Canticles (Magnificat, Benedictus etc). The Kanon included here includes poetic verses (megalynária) about the Magi and Herodes. Another megalynárion follows, written by St Joannes Koukouzeles, a Byzantine composer and singer of the 14th century. The ‘Sarum’ prosa that follows, Te laudant alme Rex is a piece which in its extension of text and music is comparable to Byzantine kalophōnía. “The Sarum Processional directs that verses of the prosa for Christmas Day Te laudant alme Rex should be chanted first with their texts by three clerics, then by the choir as a wordless melisma” (booklet). It is followed by the antiphon Hodie Christus natus est. A comparable proclamation of Jesus’s birth is the prologue of the hymn (kontákion) for the Nativity of Christ in Byzantine chant. The Kyrie Deus Creator omnium is an example of a chant with tropes – textual extensions of a liturgical text. This opening section of the Mass is always followed attacca by the Gloria. Here we have a polyphonic version that has been reconstructed from two sources, among them the Old Hall manuscript. This section ends with a communion verse for Christmas: “The Lord has sent redemption to his people, in peace. Alleluia”. It was written by a monk, Agathon, who was the brother of Xenos Korones, a Byzantine composer of the 14th century.

The disc closes with the Magnificat, sung at the Second Vespers on Christmas Evening, embraced by the antiphon Hodie Christus natus est. The Magnificat is taken from a 15th-century manuscript preserved in Cambridge; it is scored for three voices. “On this recording we emphasize its close relationship to spontaneous harmonization by alternating full performances of its three-part texture by soloists with renderings of only its lower two voices by the choir.”

“Cappella Romana is a professional vocal ensemble that performs early and contemporary sacred classical music in the Christian traditions of East and West”, we read on its website. It was founded in 1991 and has built up an impressive discography of music that one may not hear that often. Its performances and recordings are based on thorough research, and that shows in the lengthy and highly informative liner-notes by Alexander Lingas. Earlier, I reviewed a recording of liturgical music from Cyprus), which I very much enjoyed. This disc is a most impressive testimony, both of the liturgical traditions to which it is devoted and to the way the selected repertoire is performed. In the Byzantine pieces we mostly hear the lower voices, and their singing is spellbinding, if one is receptive to it. Those who have heard Russian Orthodox chant may recognize the style. There are similarities, but also differences. The lyrics are printed in the booklet in the original Greek characters, which avoids the problematic transcription and is also nice for those who have learnt to read them. In the pieces from English tradition, we also hear the higher voices; the singing there is just as good as that of the lower voices in the Byzantine chants.

The programme has been put together in a creative manner, interestingly pairing pieces which are comparable in content and sometimes even in the treatment of the material. This way the similarities and differences are clearly exposed. The atmosphere of a Christmas celebration is admirably suggested.

If you look for a disc for Christmastide that is entirely different from what you may have in your collection, and certainly from what you may hear in churches, concert halls and on the radio during December, this is the one you should investigate.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

[From the Services of Christmas Eve]

anon

Sarum Responsory at Vespers for the Vigil of the Nativity of the Lord: Iudea et Hierusalem

Acclamations Sung at the Prókypsis of the Emperor

Xénos Korónes (11th C)

Kalophonic Polychrónion

[From the Services of Christmas Day]

anon

Motet: Ovet mundus letabundus

Pentekostária (Tropes of Psalm 50) for Christmas Matins

Sarum Responsory from the Second Nocturn of Matins: O magnum mysterium

Kosmas of Jerusalem (8th C)

First Kanon of Christmas Matins:

Ode 9 with Megalynária

Joannes Koukouzeles (c1280-1360/75)

Kalophonic Megalynárion and Katavasía of Ode 9

anon

Prosa from the Sarum Processionale: Te laudant alme Rex

Entrance Antiphon: Hodie Christus natus est

St. Romanos the Melodist (6th C)

Prologue of the Kontákion for the Nativity of Christ

anon

Kyrie for Principal Double Feasts: Deus Creator omnium

Gloria in excelsis

Agáthon Korónes (11th C)

Communion Verse for Christmas

[At Second Vespers on Christmas Evening]

anon

Antiphon before the Magnificat: Hodie Christus natus est

Magnificat

Antiphon after the Magnificat: Hodie Christus natus est