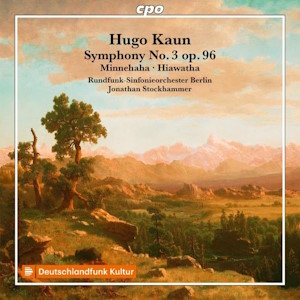

Hugo Kaun (1863-1932)

Symphony No.3 in E minor, Op.96 (1913)

Im Unwald; two symphonic poems after Longfellow, Op.42 (1901)

Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra/Jonathan Stockhammer

rec. 2022, Haus des Rundfunks, Saal 1, Berlin

cpo 555 572-2 [77]

Hugo Kaun is a new discovery for me, a German composer born in Berlin in 1863 who moved to Milwaukee, America’s most ‘German’ city, in 1887. He’d received a rather scattered musical training in his home city – though he had been taught music theory by Friedrich Kiel – and was principally interested in songs, orchestrated lieder settings and choral conducting. In his 1932 autobiography he mentions being by a lake with friends on a sunny September morning when suddenly a group of Native Americans in war paint arrived to water their horses. This image never left him and must have crystallised something in him. Longfellow had died five years before he’d come to America but remained immensely popular. Perhaps Kaun knew that a fellow temporary emigree Dvořák had spoken of toying with the idea of a Hiawatha cantata. In any event he determined to write two symphonic poems after Longfellow which he claimed to have done in the forests of northern Wisconsin.

Getting an idea of the chronology is tricky and the booklet notes, though extensive and well-written, aren’t able to help. Kaun seems to have visited Wisconsin in 1891 but the first time he conducted the two symphonic poems, Minnehaha and Hiawatha – together called Im Urwald – was in Berlin in 1901 with the Berlin Philharmonic. Imslp.org suggests 1901 as the date of composition with a piano four-hands version of Hiawatha appearing in 1902; it also suggests the first performance of the poems was in 1903 in Chicago with Theodore Thomas conducting but that seems to be the American première, if cpo is correct.

After the big build-up, what about the music? Minnehaha is twelve minutes long in this performance and is predicated on a Lisztian-Wagnerian plan. The free-flowing fluid Wagnerian influence is allied to precise incidents and reminiscences, to motifs and expressive writing creating a strong musical narrative. The increasing turbulence of the music, leading to Minnehaha’s death, offers Kaun an opportunity to write a Funeral March of vivid intensity before ending the work with the resolve of pizzicati. Its companion Hiawatha opens with a hunting horn motif and presents a portrait of the hero. Possibly Kaun used Liszt’s Faust Symphony as something of a model. In any case the music embraces the idyllic and the noble, burgeoning romance and paragraphs of exuberance – strong, striding thematic composition graced with clever wind writing. When the horns return Kaun unleashes a grand processional to close the work.

It may or may not be a coincidence that Coleridge-Taylor’s Hiawatha trilogy was composed during the time Kaun was working on his two symphonic poems. However there seems no reason to doubt Kaun when he says that he’d been thinking about Longfellow since at least 1890.

Kaun returned to Germany permanently in 1902 and by 1908 had produced his Second Symphony which was conducted by Nikisch in Leipzig, Frederick Stock in Chicago and Weingartner in Vienna. There’s even a reference to a performance in Tsingtao in China by the orchestra of a visiting German marine battalion. I’m not quite sure what they sounded like. His Third Symphony followed in 1913 and was to be conducted by Furtwängler and Pfitzner amongst leading luminaries. It’s in four large-scale movements, the work lasting some 50 minutes.

The opening movement is measured and lasts a quarter-of-an-hour. It’s a strongly late-Romantic work, with plenty of detail and contrast, some decidedly Im Walde in inspiration, irradiated in this first movement with chorale themes too. Some passages strongly suggest a Brucknerian element. The Scherzo is bluffly genial though it has capricious features and some further Brucknerian cadences – Kaun is on record as having admired the composer. Though parts of the slow movement are rather inert it’s well orchestrated and its calmness doesn’t preclude the introduction of nocturnal or mysterioso qualities – perhaps it’s best thought of as a forest at twilight, if you’re being descriptive or fanciful – though as it develops it gathers up more and more Wagnerian accretions. In some ways – intervallic, harmonic – the finale is the most interesting movement, the music gathering itself through contrasting incident until it unleashes a celebratory hymn to end in splendid triumph.

The Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra under Jonathan Stockhammer play with commendable commitment though the recording is just a little ‘soft’ for my tastes. It doesn’t sound quite resplendent enough. The jewel box track listing is wrong so follow the one in the booklet.

Having sampled his interesting but up-and-down, in-and-out, never wholly convincing Third Symphony, naturally I’m wondering about the Second.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from