Déjà Review: this review was first published in November 2005 and the recording is still available.

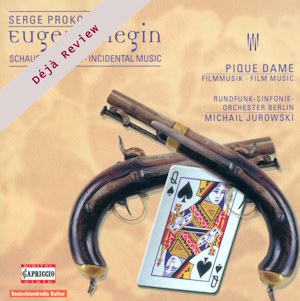

Serge Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Eugene Onegin op. 71, Incidental music to Alexander Pushkin’s verse novel adapted for the stage by Sigismund Krzyzanowski for speakers, chorus and orchestra

Pique Dame op. 70, Music for an unrealised film based on Alexander Pushkin’s novella (1936)

Chulpan Chamatova; Jacob Küf (speakers)

Boris Statsenko (baritone)

RIAS-Kammerchor

Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester/Michail Jurowski

rec. 2003/04, Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin-Dahlem

Capriccio 67149/50 [2 CDs: 110]

In 1936, the Soviet Union was preparing for a major celebration the following year to mark the centenary of the death of one of Russia’s most revered cultural figures, Alexander Pushkin. Among the planned events was a dramatisation of the great verse novel Eugene Onegin with integrated music by Prokofiev. By December 1936 preparations by the Moscow State Chamber Theatre were advanced, much of the music was written, sets had been made and costumes sewn. Then Prokofiev got a letter from the Theatre. Capriccio publishes it for the first time in the CD booklet:-

“The All-Union Committee for Art Affairs has given us categorical instructions not to perform the play Eugene Onegin …. you are not to conduct any more work … on the music. The play…is herewith cancelled.”

The production had fallen foul of the Main Committee for Repertoires that had sent in an inspection team of Pushkin Scholars to vet things. 1936 was a perilous year for the arts in the USSR. Pravda had been attacking artists for bourgeois formalism. In January Stalin had personally ordered the shut-down of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth in the middle of a successful run the day after seeing the opera. It could not be a work of the people because Stalin could not detect any decent melody. Shostakovich was lucky. Stalin had certainly shot people for less than writing tunes he couldn’t whistle.

As far as I am aware, the first attempt to stage this project took place only nine years ago in the remote Russian town of Yekaterinsburg. There have been recordings of selected orchestral numbers from the work, but apart from this CD, there is only one other recording currently available that uses all the music that survives. It was from Chandos, using English forces under Sir Edward Downes.

Those who have never heard the music in context are likely to be astounded by its quality. Superb melody abounds starting with a haunting oboe solo that is then developed with irresistible, expanding orchestration. An obvious irony is that even Stalin might have liked it. There is dance music that shows off Prokofiev’s gifts as a great composer for the ballet with some delightful numbers that include the inevitable ball scene crops up in so many of Prokofiev’s dramatic works. Above all, the music has dramatic impact appropriate to the text, enhanced by the composer treating some tunes as repeating leitmotivs in a way that would, I am sure, have given a full performance of the play great cumulative power. The quality is such that Prokofiev incorporated some of the music into other works including the opera War and Peace, and the ballet Cinderella.

The problem for the producers of the discs was how to realise the music in dramatic context. This is not just incidental music. There is song, chorus and orchestral music that backs spoken word, melodrama fashion. An additional problem is that some of the music survives in fragments and some only in piano score.

The Chandos version took a more speculative, reconstructionist course than the current recording. There was considerably more spoken word either side of music sections as well as completion of the fragments. The result is that the recording runs to two full discs as opposed to Capriccio’s one. There was also orchestration of some of the dance numbers that survived in piano score only, whereas here they are simply played on the keyboard, although some of Edward Downes’s orchestrations are re-used.

Perhaps the most impactful difference between the two recordings is that Chandos has the words, which are given to narrator as well as to main characters, delivered in English. Spoken by well-known British actors, this has the advantage meaning that Anglophone audiences know what is being said without recourse to a booklet translation. Some, including myself, consider the loss of idiomatic Russian too great a cost.

This Capriccio recording has the Russian voices intoning with far greater dramatic effect. On Chandos, Timothy West as the narrator has a bland, polite style that sounds as if he is delivering a lunch-time poetry reading at a Women’s Institute in Surrey. The Russian Tatiana, Chulpan Chamatova, is particularly striking although it was a shock when she first speaks because she is recorded quite loud as if in an echo chamber. But her delivery of Tatiana’s Dream has an impassioned, sibilant sexiness – backed by Prokofiev’s intense music – that seems to me entirely appropriate, especially if you agree with Canadian Pushkin scholar, J. Douglas Clayton’s assertion a few years ago that Tatiana’s dream is “masturbatory”. It is in stark contrast to Niamh Cusack on Chandos who sounds as if she’s in one of those old Jane Austen costume drama movies.

The playing of the Berlin RSO is immaculate and sumptuous, perhaps a little languid for some but there is beautiful sound in which to revel, well recorded.

The same applies to the “bonus” disc which contains music from another aborted project designed for the Pushkin centenary. This was a film based on the novella, Pique Dame. It was thought that Stalin would not tolerate films being shot on subjects that were not contemporary in content, by which time Prokofiev had written and orchestrated most of the music. I get the impression he was putting less effort into this than in Eugene Onegin but there is much to delight, including an inevitable ball scene with a delicious trumpet solo.

The booklet essay does not even mention Pique Dame but is detailed on the misfortunes of Eugene Onegin. I felt that the best way to listen to the latter was to follow the Russian with English translation and read up a synopsis of the action between numbers. But the booklet has no synopsis and although the text appears in French, German and English, it does not, perversely, have the Russian so it is impossible to know where you are within numbers. Also, all the track titles at the beginning of the book are only in German which may pose cross-referencing problems.

This double disc set represents an important addition to the Prokofiev recorded canon. Eugene Onegin was a revelation to me and made me think what a wonderful opera Prokofiev might have produced on Pushkin’s masterpiece. But it would, of course, have been unthinkable – a heresy – to try and follow Tchaikovsky’s Onegin, that popular pillar of Russian culture.

John Leeman

Previous review: Rob Barnett (October 2005)

Help us financially by purchasing from