Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Piano Sonata No 1 in D minor, Op 28, Original version (1907)

Preludes Op 32: No 2 in B-flat minor, No 7 in F major, No 8 in A minor, No 13 in D-flat major

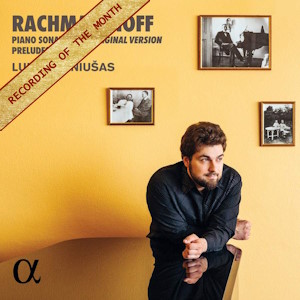

Lukas Geniušas (piano)

rec. 2023, Villa Senar, Weggis, Switzerland

Alpha Classics 997 [55]

This remarkable recital was recorded on Rachmaninov’s own Steinway, at his former lakeside home in Switzerland. But there is more: in the 150th anniversary year, this may be the nearest to an important discovery, or rather recovery.

Rachmaninov wrote the Piano Sonata No 1 in 1907 in Dresden. He told one correspondent that it was “absolutely wild and interminably long”, and that he planned to shorten it from its around 45 minutes. The newly truncated published form was indeed over 100 bars shorter. The Moscow premiere met with a lukewarm reception. After a few performances, the composer abandoned the piece, and never played it after he left Russia, despite his new life as a touring piano virtuoso. The cut version is the only one in print. Piano Sonata No. 2 suffered a similar fate, but after its initial publication. It left a muddle of two printed approved editions, one far shorter than the other, and Vladimir Horowitz’s later hybrid version. That was a free-for-all of pianists’ own versions on disc, some with such useless descriptions as “based on Horowitz”.

Enter Lithuanian-Russian pianist Lukas Geniušas. As the booklet says, he played the standard edition of the First Sonata for a number of years. He then contacted the Russian National Museum of Music in Moscow, which keeps the manuscript of the unabridged original version. He writes: “Having delved into the original, I knew I had to make it public […] It seemed important and fair […] I realized that it was going to be my main project for Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversary year, and then the incredible chance came up to record it on the instrument that belonged to him.”

Musicologist Layla Kandaurova wrote valuable booklet notes. (I am quoting from them liberally, with thanks: my review would be noticeably poorer without those quotations.) She offers plausible explanations why Rachmaninov truncated the initial score, even if he had once considered it finished enough to share with others. She suggests: “Rachmaninoff ventured outside the compositional realm he was admired for. Instead of soaring, extensive melodies of immediate appeal […] he indulges in a sophisticated, somewhat Lisztian compositional game of weaving the sprawling canvas of the sonata with its fiery climaxes and an array of themes from a number of short motifs, musical gestures even, laden with compressed meaning. A sole interval. A fragment of a scale. A brooding Phrygian sonority. A string of repeated notes, momentarily evoking syllabic chanting.The late 19th-century romantic greats approached these musical bits and pieces as cells from which they grew monumental structures. […] The polyphonic mastery, thematic ingenuity and overall compositional prowess that Rachmaninoff exhibits in the sonata are awe-inspiring […] This work, most likely, came across as vague and cerebral.”

I would add that Rachmaninov was spending three years in Dresden, learning German. He was close to those European models, and could hear concerts in Dresden and nearby Leipzig. Perhaps the sonata’s new style was a response to these central-European stimuli, as was its programmatic background from Goethe’s Faust, and Liszt’s symphony on that subject, with its three movements representing respectively Faust, Gretchen and Mephistopheles. Rachmaninov spoke of this programme even after he had published the work, but only to a select few colleagues. He may have lost confidence – a problem he occasionallly suffered from – in what he had worked so hard to achieve in the original version of his innovative First Sonata.

There is regrettably no record in the booklet of the exact nature of all the omissions which have been restored. That would have required a lot of space, but Kandaurova notes “how the (original) recapitulation of the 1st movement (with its second subject, a signature Rachmaninoff Orthodox-psalmody-turned-piano-music in glowing C major, followed by a voluminous climax) became a completely different, shorter and more ‘logical’ recapitulation with both themes tautly stating the tonic. This is how the transitional episodes in the finale – some of them really quite static and also fiendishly difficult to play – vanished or got rewritten.”

But the last word on the original version should come from Lukas Geniušas. He writes: “There is a lot lost between the first and second editions. I know it goes against the grain, but I would name this sonata to be one of, if not the best (of), Rachmaninoff’s solo piano works. Its shattering might, its splendour and scale can only be likened to the Third Piano Concerto, which was written soon after […] What fascinates me is a unique chance to have a glimpse of the composer’s intention, almost trace his thought […] It is Rachmaninoff at his zenith, the peak of his powers, a musical idiom full-blown and full-bodied. A masterpiece.”

The mention of the relation to the Third Concerto reminds us that the composer needed time and space to drive his ideas home, and large sequences to build powerful climaxes. That is the case in the Second Symphony, composed alongside the First Sonata. Put simply, the best Rachmaninov is the uncut Rachmaninov, which is why this release is so important. But do not worry that it will be too long. A 36-minute work has become a 42-minute one, and an even better one, because of its enhanced “splendour and scale”, to quote the pianist.

The value if the work would be limited if the playing were weak, or the longer span of the original version hard to listen to. But to my ears neither objection holds. The work remains fascinating, maybe more fascinating than the published version. It is as revealing to hear this, assuming one knows the published version, as when one first hears an uncut Second Symphony, or the first edition of the Second Sonata rather than the ubiquitous shorter second version.

One reason why the additional music is so powerful is that the whole is powerfully played. Geniušas already has a notable pedigree in Rachmaninov recordings, and all his technical gifts and emotional engagement with the music are on display. The four Preludes from Op 32 make very attractive fillers, but he has given us both sets before. The disc might instead have included a recording of the published Sonata No 1, or at least of the outer movements, since there were no changes in the middle movement. That would have been helpful and enlightening, especially for newcomers to the work. The sound is very good. The old instrument is a touch tinny in the very high treble once or twice, but otherwise it sounds mellow and powerful, with a rich bass.

Lukas Geniušas says in his YouTube presentation of the disc that the published version is very difficult to play (“most pianists don’t play it”) but the original version is “three times” harder. So, he does not think he will be playing the original much in concert: all the more reason to get this disc.

Roy Westbrook

Help us financially by purchasing from