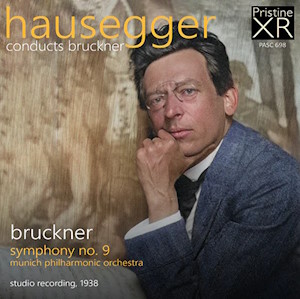

Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Symphony No. 9 (ed. Alfred Orel)

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra/Siegmund von Hausegger

rec. April 1938, Munich

Pristine Audio PASC698 [55]

If the cult of Günter Wand came and went with the turn of the millennium, the paradigm of Bruckner performance that he established remains doggedly alive in recording after recording that present these symphonies as monolithic, impassive, and bereft of their essential carnality. Opposing interpretive views have become so rare – Daniel Barenboim’s cycle with the Staatskapelle Berlin and Manfred Honeck’s Pittsburgh recording of the Ninth Symphony come to mind among the most distinguished recent dissenting readings – that it is easy to simply believe that Bruckner intended his music to be boring. Buried deep in the discographical past, however, another world of alternative possibilities exists. Siegmund von Hausegger’s recording of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony comes from an age of Bruckner interpretation that was predicated on the belief that performance of this music was a living act of celebration rather than the miming of dead ritual.

Not only did the coming of age of the conductor overlap temporally while Bruckner scrambled against destiny to complete his Ninth Symphony, he was also a vital part of its reception history, being involved with the restoration and subsequent premiere of the original score. That sense of personal investment remained vehemently palpable several years later when he conducted the Munich Philharmonic in the symphony’s first-ever complete commercial recording in 1938.

It is tempting to speculate whether Hausegger was aware of the existential questions that Bruckner grappled with during the composition of his Ninth in his final years. The composer recorded a quote by the anatomist Josef Hyrtl in his diary, which led him to ask: “Is that which Faith calls the immortal soul of man only an organic reaction of the brain?” Whatever the answer, this reading of the composer’s symphonic valedictory nonetheless seems to intuit their presence. Take a listen to the first movement, where the conductor skilfully cranks up the tension in the opening bars of the first movement through subtle manipulations of tempi, until its explosive release in the unison statement of the D-minor theme. Whereas modern performances typically play this moment as simply a ho-hum working out of mere notes on paper, Hausegger conveys here a simultaneous vision of celestial ecstasy and apocalyptic terror felt as if in the flesh. Relief arrives momentarily when Hausegger unveils the secondary theme, phrased with great suppleness and riding on plush chords billowing from Munich’s low brass and strings, but expressive duality remains the core of this performance. By the time the listener arrives at the blazing coda, they may well wonder whether its fanfares are auguring the coming of God’s mercy or His wrath.

The cyclonic interpretation of the scherzo which follows is one of the fastest on records, bested only by a broadcast tape made a few years later by Hausegger’s successor, Oswald Kabasta. If the pace leaves the Munich Philharmonic audibly struggling at moments (all the more remarkable that only five years later, Kabasta would have the same orchestra playing even faster and with astounding unanimity to boot), Hausegger still aptly projects this music’s essential fury, while most of his latter-day counterparts only manage to sound fustian.

Hausegger’s performance of the third movement faintly reminds one of Herbert von Karajan’s live May 1978 Vienna Philharmonic recording (once available in fine sound on Andante SC-A-4070). Both conductors imparted a sense of richness and sensuality that many contemporary performances miss. They diverge in crucial ways, however. Karajan prized sleekness, fluctuations of tempi calibrated with almost imperceptible fluidity, and an even corporate sonority that slightly favored the treble end of the strings. Hausegger preferred punchier attacks, his rubati were dramatic, and his orchestral blend titled baritonal. Maybe the greatest differences are in these conductors’ respective approaches to momentum: if Karajan gives the impression that heaven can wait, Hausegger, especially when he is building towards climaxes, appears ready to go stomping up to the pearly gates in hiking boots. Yet, even as he bounds forward, he knows to also pull back breathtakingly, such as in the ecstatic, RVW-esque hymn (starting at 14:32), or at the hellish dissonance that crowns the movement (at 18:43).

For all its artistic excellence and historic worth, reissues of Hausegger’s Bruckner Ninth have been rare. On physical CD, it appeared in the mid-1990s on a Preiser (90148) and as part of a two-volume EMI compilation of early Bruckner recordings (CHS5 66210-2). The sound on those discs was solid, if more an approximation of what the music engraved on those shellac grooves, with the latter tending to fuzziness, while the latter had more presence, but also sounded pinched. More recently, it was released on CD-R and lossless digital download by St. Laurent Studio (YSL 78-259) in a more faithful transfer with discreetly applied noise reduction. Andrew Rose’s transfer on this Pristine release navigates a middle course between fidelity and interventionism. Purists may recoil at the mention of “ambient stereo”, yet Rose applies such modern enhancements with sensitivity. He skillfully imparts the illusion of openness not present on the original 78s, which sound a touch cramped.

Hausegger’s 1939 recording of the Ninth is one of the most compelling artifacts from a now almost vanished world of interpretive meaning and values. Its revival by Pristine Audio, inexpensively priced, is something Bruckner collectors should rejoice in.

Nestor Castiglione

Availability: Pristine Classical