Visiting Robert Massard

by Ralph Moore

Having already written two surveys of recordings (Part I ~ Part II) by celebrated French baritone Robert Massard, I offer this is as a follow-up article, as it were, as my wife and I recently visited him at his home in Pau, in the département of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques, where he was born and where he has lived since his retirement from the stage in 1984. He chose to return to his native city as he feels physically linked to the nearby Pyrenees mountains and spoke movingly of the love and devotion shown to him during his happy childhood and young adulthood there by his parents – and also of their trials in their last illnesses. He lost his wife, Madeleine, five years ago; she was a dancer who gave up her career to support his – and by all accounts a delightful person.

Driving down the Western seaboard of France on a round trip of 1700 miles to Pau and back, our weather was unseasonably and unfailingly warm, bright and sunny – matched by the sunniness of M. Massard’s personality; he is extraordinarily vital and humorous for a man who has just celebrated his 98th birthday. His personal charm is infectious and we were welcomed with great warmth, hospitality and courtesy; our time spent with him was punctuated by phone calls from friends and family, making readily apparent the affection he both inspires in and accords towards others whom he addresses as “Mon cher”, signing off with “Je t’embrasse très fort”… We were also able to spend some time in the amiable company of his long-time pianist friend and accompanist, Mme Chantal Pichou, who teaches in Pau.

We talked somewhat of his youth; he inherited his aptitude for singing from his father who had a fine voice, but in 1939 M. Massard senior lost his job as Sales Director at Renault when the factory was turned over to produce armaments, so funds were not available for Robert to enter the music conservatory and as he was unable to obtain a grant or any patronage he was obliged to choose a profession – that of motor mechanic. Nonetheless, he won first prize in singing competitions in Pau and Bayonne and continued to sing for pleasure both solo and in choirs but never considered a professional career.

However, fate, chance or Providence decreed otherwise; his success, he maintains, was the result of great good fortune as well as his own talent and determination, and dependent upon a sequence of events which could never be repeated today: “Tout s’est enchaîné” (One thing immediately followed another) and “L’étincelle a enflammé le foyer” (The spark lit the hearth; i.e. great things grew from small beginnings). His father still had contacts in the automobile industry, one of whom heard him singing at a banquet in the Pau casino and was friends with Georges Hirsch, director of the Réunion des Théâtres Lyriques Nationaux. He persuaded M. Hirsch to arrange for Robert to be auditioned at L’Opéra de Paris in 1951 – along with Nicolai Gedda and Victoria de los Ángeles, who were just beginning their professional careers. As a result, Hirsch offered him a contract despite his having no formal training and no knowledge of solfège. He joined the Opéra under the new Director, Maurice Lehmann, who ignored him for months, then persecuted him, clearly wanting to be rid of him, and only finally gave him a debut role as the High Priest in Samson et Dalila when he discovered that Massard had been offered by the Aix-en-Provence Festival director Gabriel Dussurget the unlikely role of Thoas in Iphigénie en Tauride under no less a figure than Carlo Maria Giulini; meanwhile, he studied hard for two years with Mme Madeleine Milhaud (wife of the composer) at the Schola Cantorum and was helped and encouraged by veteran bass-baritone Charles Cambon.

Despite cabals, claques, jealousy and ridicule from other singers because of his lack of technical knowledge, he persevered in “un milieu de requin” (a shark-infested environment). Among his many amusing anecdotes was one about a certain mezzo-soprano who shall remain nameless and who tried to stitch him up by employing a claque to boo him and about whom he had some strong words to say. He also relishes telling of his introduction to Giulini by Dussurget: “Je vous présente le jeune Massard; il ne sait rien” (Let me introduce to you the young Massard; he knows nothing); to which the amiable Giulini replied – and here Robert imitates Giulini’s Italian accent, with trilled r’s – “Meme s’il rate trois ou quatre mesures, Gabriel, je le rattraperai!” (Even if he misses out three or four bars, Gabriel, I’ll catch up with him!)

Despite the humility with which Robert speaks of his progress, it is clear that he possessed extraordinary powers of perseverance but above all a passion for singing great music. The extraordinary thing is that he never once took a formal singing lesson; indeed, his experience with voice teachers was usually negative. One summoned him only to try to convince him that he was a tenor manqué, a suggestion he firmly resisted. He was, of course, a baryton aigu (a high baritone, almost a baryton-martin) and not a baryton basse – in other words, a true Verdi baritone, hence his ringing top As, his pre-eminence as Rigoletto and the ease with which he could cope with the tessitura of the Barber. This facility was allied to the unparalleled evenness of his line – “Il faut toujours articuler dans le legato” – great verbal dexterity and an unfailing clarity of diction in roles such as Rimbaud in Le comte d’Ory, which explains why, when he was still in training, he was thinking that if he could not succeed as a singer he would try a career as an actor.

As it turned out, he was a pensionnaire at the Paris Opéra from October 1951 until July 1978 and sustained an inordinately long career of thirty-three years, which might yet have been further prolonged had he not chosen, as so many wise singers such as Dame Janet Baker have done, to retire at 59 while still at the peak of his powers. As he puts it, he preferred people to remark “Déjà?” (Already? i.e. “So soon?”) rather than “Encore lui?” (Him again? i.e. “Still singing?”).

Among the many joys of his career, there were of course disappointments, perhaps the greatest being the closure of the Opéra-Comique and the disbanding of its troupe of singers in 1972 when it ran out of money owing to poor management, which he considers to have been a disaster. High points include being the first Frenchman to sing Rigoletto in Russia and his recording of Carmen with Maria Callas, whom he found to be utterly professional and considerate but also to have an air of sadness about her. He is dismissive of her supposed vocal faults in comparison with the profundity of her artistry; just as he was profoundly affected by his first experience of a complete opera – Thaïs, in Bordeaux – Callas’ Norma moved him to tears, and he considers her to have been the complete tragédienne lyrique.

Further cherished memories include being presented to the dignitaries below, singing Frank Martin’s In Terra Pax for Paul VI in 1969 and being created Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1975, then Officier of that same Order in 2002.

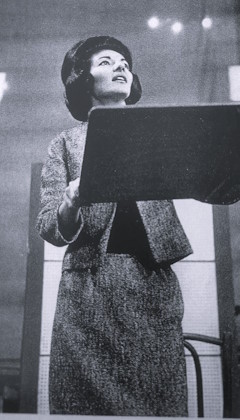

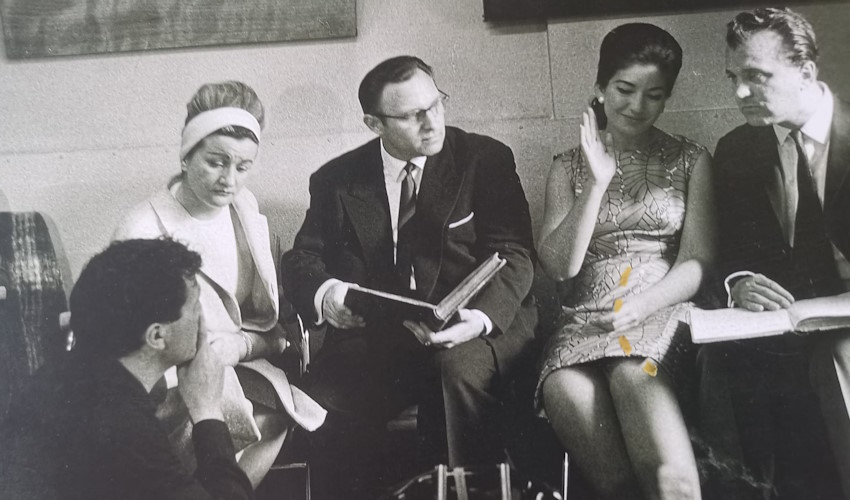

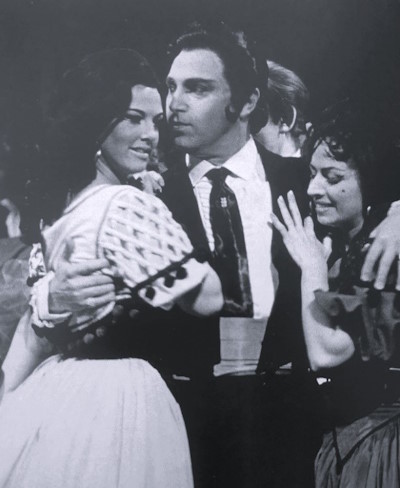

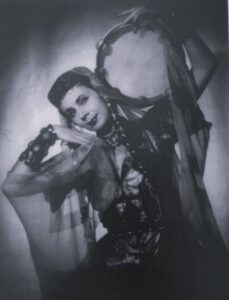

He gave me a wealth of photographs of him, his co-singers and family, both colour and black and white, from which I have endeavoured, with difficulty, to select some of the most interesting. Note how beautiful and detailed are some of the costumes of that era.

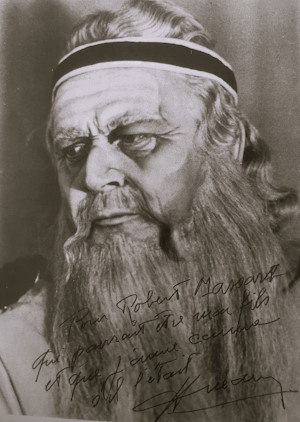

Bass Henri Médus (below left, as the Old Hebrew in Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila, the role he sings in the studio recording I recommend in my survey of that opera) was the man who taught him the art of make-up, a skill he took to such a point that as some characters he became completely unrecognisable (as shown below right – Sancho Panza in Massenet’s Don Quichotte).

He of course sang with a host of famous singers, some of whom are depicted below.