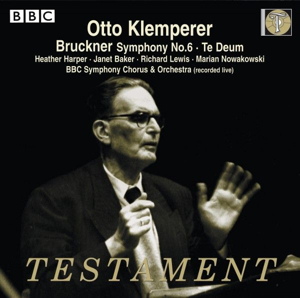

Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Symphony No. 6 in A major, WAB 106 (1879-1881)

Te Deum In C major, WAB 45 (1881-1884)

Heather Harper (soprano), Janet Baker (mezzo-soprano), Richard Lewis (tenor), Marian Nowakowski (bass)

BBC Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Otto Klemperer

rec. live radio broadcast, 12 February 1961, Maida Vale Studios, London, UK

Testament SBT1354 [77]

I should start by nailing my colours to the mast and declaring that I am a great Klemperer fan. Particular favourites include the Philharmonia recording of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony, that remains one of the benchmarks with which I compare all others; there is also a performance of Mendelssohn’s Fingal’s Cave, live with the Bavarian RSO, whose elemental splendour invokes the might of the whole northern Atlantic in a way that smashes the pretensions of the Historically Informed Performance movement onto the rocks of the Hebrides forever in my mind. There are many others too, from composers as diverse as Richard Strauss and Tchaikovsky. Yet I do struggle with his Bruckner. The best of his ‘official’ recordings for me, is the recording of the Seventh Symphony with the Philharmonia made for EMI (now Warner), that I find is a reading of supreme logic and grandeur, well-nigh perfect in three movements, yet lacking a certain spirituality, Innigkeit even, in the most solemn of threnodies that is the Adagio. Even better, to my ears, is a live concert relay of the Eighth Symphony, made with the Cologne RSO in 1957 which, unlike his studio recording, is not only uncut, but is also utterly magnificent on so many levels. His recording of the Sixth (EMI/Warner again) is also venerated by many notable critics: Richard Osborne in Gramophone Magazine, Dave Hurwitz of Classics Today, as well as Messrs Greenfield, Layton and March in the indefatigable Penguin Stereo Guide, amongst others – but I have never been so sure. His way with the wonderful Adagio in this recording of the symphony, swift, almost devoid of feeling and a willingness of explore its sense of wonder and mystery, quite knocks it out of the court for me. So I wondered if this BBC radio broadcast would be any different.

What needs to be declared first of all, not least since it has apparently fooled others, is that this is a mono recording of a broadcast made from a BBC radio studio in February 1961 and while the sound is clear, well balanced and listenable on this CD only release, it is not state of the art and is indeed even slightly disappointing for the early 1960’s. So if you are wanting, or even expecting, spectacular and luminous sound, then this is not for you. On the other hand, if you do not mind such minor inconveniences, then do please read on.

To be frank, the symphony gets off to a really bad start – I have never heard this work begin so slowly; nor, on this showing, does it seem has the BBC Symphony Orchestra before or, probably, since. Hugh Bean, one of the concert Masters of the great Philharmonia Orchestra, once recounted (during the film Great Conductors of the Twentieth Century) that for Klemperer, accuracy of ensemble was not a priority – “If it happened, he was pleased; but his priority was clarity …” and so here at the beginning of the symphony, ensemble teeters precariously on the brink of disaster, although somehow the orchestra just about stays on track. However, the whole first movement is neither convincing nor enjoyable, with the quieter moments rushed over; it sounds almost as if it is an interpretation that is still evolving. The second movement Adagio clocks in at just over thirteen minutes, nearly a whole minute and a half quicker than his EMI/Warner New Philharmonia account – and I thought that was fast. At this speed, it is more Andante than Adagio and one wonders if Klemperer was just trying to get the whole thing over and done with, his approach being so terse, almost perfunctory. The third movement Scherzo is better, the trio a little slow perhaps as was always the wont of this conductor, but the finale is much, much better; it’s as if at this point conductor and orchestra seem to gel and the results are splendid.

This is of course the BBC Symphony Orchestra, not Klemperer’s usual London band, EMI’s refusal to countenance a recording of either of the Te Deum or Sixth Symphony, prompting the conductor to instead court the BBC and its London-based band; it’s to Klemperer’s credit that he obtains from them dedicated, if not flawless, playing. It was therefore interesting to compare this performance with a live one with the Concertgebouw Orchestra made some four months later and available on the Andromeda label, as well as the New Philharmonia studio version taped three years after. The sound on the Amsterdam recording is as good as the BBC one and this orchestra, better versed in both Bruckner as well as Klemperer’s idiosyncratic podium manner, seems to be able to deliver the interpretation more convincingly. The start is again just as slow and the gear change into the final pages just as clunky (issues that the conductor had resolved by the time of the EMI recording), but they are carried out with more aplomb in Amsterdam than they were in the BBC studio.

So as far as the symphony goes, this release is superfluous. If you want Klemperer in this work, then his EMI/Warner New Philharmonia recording is better played, better recorded and more of a piece as an interpretation; live, the Concertgebouw delivers the slightly different earlier interpretation far more convincingly than the BBC SO and the sound is almost as good. Both are to be preferred to this BBC account, but neither supplants my own top recommendations. These would include Eugen Jochum, whose unique and fluid way with Bruckner, works especially well with the Sixth in both his studio versions from Bavaria (DG) and Dresden (EMI/Warner), as well as a late, live recording made with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1980 (available on Tahra). Karajan’s recording (on DG), curiously, starts out as if sounding like a straight run-through for a first rehearsal but then grows into a performance of real stature, much admired by the composer and musicologist Robert Simpson, no less. Celibidache with the Munich PO (EMI/Warner) combines slower than usual tempos with unique insights that work especially well in this symphony while, at another extreme, Sawallisch with the Bavarian State Orchestra (on Orfeo) finds real fire in the music, expertly balancing it with its inherent grandeur. Of more recent provenance, Bernard Haitink’s last recording from 2017 (BR Classics) with the Bavarian RSO, finds similar qualities. All are supremely recommendable. The more historically minded collector would also be advised to seek out Furtwangler’s 1943 recording, shorn of its first movement, but replete with insights, plus Georg Ludwig Jochum’s (Eugen’s brother) very fine performance with the Bruckner Orchestra of Linz from 1944. And finally, Keilberth’s 1963 traversal with the Berlin PO on Teldec is also venerated by many.

If the recording of the symphony is a bit of curate’s egg, then the coupled Te Deum is pure gold, not least since this is the only recording we have (so far) of Klemperer conducting it – and very finely he does too. I got the impression that things just got better and better during this broadcast, as if orchestra and conductor were gaining an understanding of each other, so when they get to the Te Deum the music making is red-hot. He is given an excellent team of soloists, including Heather Harper, Janet Baker, Richard Lewis, as well as Marian Nowakowski and the BBC Chorus blaze away. Klemperer pilots a course between the fiery Jochum and the loftier Karajan, both with the Berlin PO on DG, and so for me this goes onto the shortlist of the very best versions of all, which all Brucknerians should strive to hear. Klemperer takes twenty-three minutes, around the norm for this work, but another version that demands to be heard is the extraordinary thirty-two minute behemoth from Celibidache in Munich (on EMI/Warner), not just because you will never hear another performance as remotely slow as this, but because Celibidache somehow pulls it off so convincingly. Last, but certainly not least, Matthew Best on Hyperion with the Corydon Orchestra and Chorus present the work on a smaller scale than those aforementioned turbo-charged podium wizards, but when his tenor soloist prayerfully intones Te ergo quaesumus, sounding for all the world as if he is on his knees in front of a simple altar with little more than a wooden cross on it, you do wonder if actually this is more what the profoundly religious Bruckner had in mind; remarkable.

A highly recommendable Te Deum then, generously coupled with a non-essential Sixth symphony.

Lee Denham

Help us financially by purchasing from