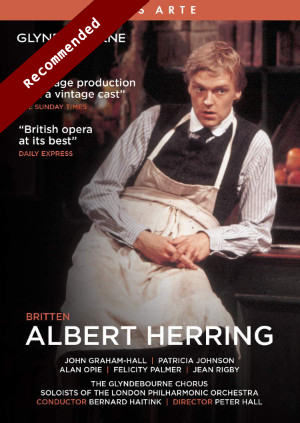

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Albert Herring (1947)

John Graham-Hall (tenor) – Albert

Patricia Johnson (soprano) – Lady Billows

Felicity Palmer (mezzo-soprano ) – Florence

Alan Opie (baritone) – Sid

Jean Rigby (mezzo-soprano) – Nancy

Glyndebourne Chorus

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Bernard Haitink

Peter Hall (producer)

rec. live, 1985, Glyndebourne Festival

Opus Arte OA1375D DVD [145]

I will begin this review with two bold statements: that Britten’s Albert Herring is the most infectiously comic opera in the English language, and that this video recording enshrines a performance of it that captures its essence to perfection. Eric Crozier’s libretto, which he hammered out in conjunction with the composer, is lightweight in entirely the right sense of the word; its humour, often sly and subtle, is conveyed in text that sparkles with enjoyment, and it still retains enough subtext on the foibles of the Victorian English class system to provide producers with the opportunity to make their own contributions without destroying the sheer sense of fun that permeates the music. Sir Peter Hall’s production, first seen at Glyndebourne nearly forty years ago, includes plenty of fresh ideas to enliven proceedings, without once setting a foot wrong. The interplay not only between the upper and the lower classes (shades of Downton Abbey, except that the upper classes here are completely oblivious to the consequences of their actions) but between the various strata of the upper and middle classes themselves, is subtly underlined time and time again. Lady Billows, the vicar and Miss Wordsworth have the etched vowels of the entitled and educated; the Mayor has been unable to shake off his Suffolk tradesman’s accent, but still finds time to look down on the more proletarian Inspector Budd; and Florence Pike, the bossy and interfering housekeeper, regards it as her duty to keep them all in order even while she worries about not receiving credit for her efforts. There are cross-currents elsewhere too, as the police inspector surreptitiously gives a conspiratorial wink to the errant Albert at the end of the proceedings. At the time of the original performances, some criticism was directed at the manner in which Hall obtained various forms of Sussex dialect from the singers; nowadays these not only seem quite appropriate, but indeed serve to reinforce the characterisation.

Hall also carefully avoids the danger of over-forensic psychological analysis of the plot. It has to be noted that Eric Crozier himself, in a sequel to the opera which took the form of a short story written some fifteen years later, developed the character of Albert by giving him a subsequent history including a career in blackmail and pornography (Britten was apparently horrified); and I have certainly read more than one article which portrays Albert’s night of adventure as the coming out of a gay young man coming to terms with his sexuality. But if this was ever in the composer’s mind, surely he would have avoided lines such as Albert’s description of his “night of dirt and worse” in the phrase “it wasn’t much fun”. Hall rightly leaves such sub-texts strictly alone, and Albert does indeed come back to Loxford “better for his holiday” as the approving Sid, Nancy and the local children proudly proclaim. Hall even retains Britten’s knowing conclusion to the opera, as Albert throws his orange blossom wreath out into the auditorium (although, this production having been filmed from the stage without an audience, this gets no reaction). The lack of an audience, and their laughter, is slightly disconcerting in places, but it does allow Hall (acting as his own video director) to obtain camera angles which would probably have been impossible under live stage conditions. There is plentiful use of close-up too, superbly capturing the excellent facial expressions of the singers and even making visual jokes of its own (as in the focus on Albert’s face with his mulish “For what?” during his Scene Two monologue).

One could go on almost indefinitely about the joys of this production, but I would not wish to spoil the surprises for those who come to this reissued video with fresh eyes. Even the slightly faded colours mesh well with the period sepia photographs that cover the orchestral interludes between the scenes (and, thank goodness, Hall resists any temptation to stage these). The varied reaction of the village worthies to the intermittently striking clock in the first scene is a masterpiece of comic timing, and the provided subtitles (which ensure that none of the wit in Crozier’s libretto is missed) are spot on even when difficult choices have to be made between simultaneous dialogue between the characters.

I have mentioned the acting abilities of these characters without once mentioning their singing, which is grossly unjust. The monstrous Lady Billows confronts the singer with the greatest challenge, ensuring that her blasts of unthinking jingoism make their truly horrendous effect as she manages to lose her notes during her speech, but Patricia Johnson rides triumphantly over the chaos. As the officious housekeeper Felicity Palmer relishes her mournful couplet “Country virgins, if there be such, think too little and see too much” as much as her more salacious gossip and attempts to boss Sid and Nancy about during preparations for the feast. Derek Hammond-Stroud lacks the sense of warmly lyrical line that John Noble brought to the role in Britten’s own recording, but his bumbling parson has a touching sense of insecurity as he clearly nourishes his helpless passion for the naïve Miss Wordsworth of Elizabeth Gale. Alexander Oliver and Richard van Allan spar with each other like Captain Mainwaring and Sergeant Wilson in Dad’s Army (could Hall possibly have had that parallel in mind?), and Alan Opie and Jean Rigby are properly warm-hearted as the young lovers. Even the children, so easily sentimentalised, are given properly cheeky characters, and Patricia Kern is a suitably overbearing Mum whose face creases in a touching manner at the moment when she realises that she has finally lost control of her son. And as that son John Graham-Hall is absolutely perfect, a young man coming to terms with life and avoiding any of that sense of coyness that Peter Pears was unable to avoid in the 1960s assumption of the role for Britten (one suspects that he may have captured some of the young spirit better in 1947). Bernard Haitink obtains spirited playing from the orchestra, although the recorded sound is quite close and raw with slightly too much emphasis on the percussion (especially the side drum in Act Three).

But even these minor details do nothing to detract from what has to be regarded as simply one of the greatest operatic videos of all time. It is splendid that it has been restored to the catalogue. There are no extras (there never were, even in the old VHS videotape by which I first got to know this production) but that is of no importance. If anyone has not seen this, they should not hesitate; even those who dislike Britten cannot fail to warm to such an engaging rendition as this. The last video issue was minimally and miserably presented, without even a booklet; this reissue now gives us an eight-page booklet including a track listing and synopsis (in English only). Subtitles come in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Help us financially by purchasing from

Additional cast

Elizabeth Gale (soprano) – Miss Wordsworth

Derek Hammond-Stroud (baritone) – Vicar

Alexander Oliver (tenor) – Mayor

Richard van Allan (bass) – Superintendent

Patricia Kern (mezzo-soprano) – Mrs Herring

Maria Bovino (soprano) – Emmie

Bernadette Lloyd (soprano) – Cis

Richard Peachey (treble) – Harry

Video details

Sound formats: Dolby digital

Region code: all regions

Picture format: 4.3