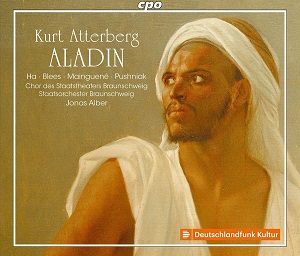

Kurt Atterberg (1887-1974)

Aladin op.43 (1936-1941), fairy-tale opera in three acts and five scenesMicael Ha (tenor), Aladin

Frank Blees (bass), Nazzredin, the Sultan

Solen Mainguené (soprano), Princess Laila, his daughter

Oleksandr Pushniak (baritone), Mulak, the Grand Vizier

Selçuk Hakan Turaşoğlu (bass), The Blind Beggar / The Spirit of the lamp

Chor des Staatstheaters Braunschweig

Staatsorchester Braunschweig/Jonas Alber

rec. live, March 2017, Staatstheater Braunschweig, Germany

Booklet contains biography, synopsis and full libretto with texts in German and English.

cpo 555 161-2 [2 CDs: 120]

Kurt Atterberg’s music has been rather well served on disc. Both cpo and Chandos recorded all the symphonies (review ~ review ~ review ~ review). Other labels – Sterling, Swedish Society, Marco Polo and BIS – followed on with an odd CD here and there. I was delighted to receive this recording. I had not heard any of Atterberg’s operas, so I looked forward to a setting of Aladin, an opportunity for the composer to come up with glittering melody, spiced with orientalisms. The notes (which I acknowledge with thanks) do not say it outright, but a handful of bumps and thuds suggests that it is a live recording.

I was interested to learn that the orchestra is one of the world’s oldest. It was established in 1587 by Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel as his court orchestra. There are many regional orchestras in Germany as a result of the conglomeration of small and large ducal and princely states that Bismark more-or-less less forced into union by 1871.

The opera took Atterberg about five years to complete; the war must have had an effect. The premiere in Stockholm in March 1941 was not an outstanding success. That may have been because the libretto is in German. One librettist, Michael Welleminsky, was a Czech Jew, the other, Bruno Hardt-Warden, was German. Atterberg was quite well known in Germany, where his earlier operas had been performed. Perhaps understandably, given the welcome given to his music over the years, his relationship with the Nazi government was somewhat equivocal. More unfortunately, when Swedish critics attacked his music as too conservative in the days of Schoenberg et al., he replied in terms which outraged liberal opinion. All in all, he was musically ostracised after 1945. Today his rhetoric would be considered racism of the worst type; the booklet quotes an extreme example. (In mitigation, there is written evidence that he appealed directly to the German government on behalf of threatened Jewish individuals.)

In contrast with the tepid reception in Sweden, the German premiere in Chemnitz in 1941 was tremendously successful. It received very laudatory reviews.

The opera is unlikely to be widely known. At the end of the review, I have supplied a synopsis for those who prefer to know the story in advance. There are five scenes in three acts.

In the opening act, tenor Michael Ha sounds strained at the top of his range. That rather spoils his opening aria, where he sings of the beauty of his dreams. By the second act, his voice has freed up considerably, and he copes with the higher notes rather better, though even here there is an occasional hint that he is not happy with the demands placed at the top of his voice. It is not particularly characterful, and is quite light with little by way of vibrato. Soprano Solen Mainguené takes the role of Princess Laila. One cannot her vocal tone as grateful – quite acidic, rather, the very opposite of creamy. She has a vibrato, fast but only mildly intrusive. She too improves as the performance progresses. At the beginning of Act 2 Scene 3, in duet with Aladin, her voice sounds lovely, but only for the minute or so whilst she is singing quietly. Once her voice comes under any pressure, the thin, constricted sounds return.

Bass Frank Blees as the Sultan Nazzredin rather spoils his part by an excessive vibrato, although his voice does not sound worn. Oleksandr Pushniak singing the part of the Grand Vizier Mulak is in good voice throughout, as is Selçuk Hakan Tiraşoğlu as the genie of the lamp and the mysterious blind beggar. The chorus is well focused, though it does not sound particularly large. The orchestra plays well, the strings are together, but the recording makes the whole band sound a trifle dull, so Atterberg’s scoring hardly shines. The voices are, for the most part, quite well balanced against the orchestra, very occasionally ‘covering’ it, reducing the melodic effect of Atterberg’s scoring.

Those who have investigated Atterberg’s orchestral output will know that he had a good melodic gift. He uses it in his last opera in the orchestral interludes and arias/duets.

This is a decent release accompanied by first-class documentation in English and German with a full libretto. It is undoubtedly welcome, but a full recommendation is not really possible given the variability of the singing of the principals, and a rather dull-sounding live recording.

Jim Westhead

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other performers

Justin Moore (tenor), Mulak’s friend

Patrick Ruyters (baritone), Mulak’s friend

Yuedong Guan (baritone), 1st Muslim

Franz Reichetseder (bass), 2nd Muslim

Synopsis

Act 1 Scene 1

Aladdin and Grand Vizier Mulak (in disguise) see the beautiful but veiled Princess Laila and both fall in love. Aladdin risks death by seeing her face, but a mysterious blind beggar tries to intervene on his behalf. He also knows of Mulak’s desire for her and for the throne of Samarkand, so he tells the disguised Vizier of an underground grotto filled with treasure and a sacred lamp. He of pure heart etc. etc. can touch the lamp and use it to gain his heart’s desire. Mulak reveals himself to the soldiers and tells Aladdin that if he will get the lamp for him, he will order Aladdin’s release.

Act 1 Scene 2

Arriving in the subterranean grotto, Aladdin manages to obtain the lamp. When he wants to keep it, Mulak blocks off the entrance and manages to find the exit, despite being temporarily blinded by the radiance of the lamp. Aladin left to his fate is despondent, but the genie of the lamp, named Dschababirah, reveals himself to be the blind beggar, and since he must obey the one who has the lamp at his command, shows Aladin the path to freedom.

Act 2 Scene 3

Aladin has reached home and, thinking of Laila, is presented with a vision of her, as in a dream. He begs the genie to bring him together with her, and the genie transforms Aladin’s home into the Sultan’s palace.

Act 2 Scene 4

The Sultan demands that his daughter Laila decide if she will marry Mulak, and gives her seven months to decide. Laila say that she loves not Mulak but Aladin, whose name she does not know even though they met briefly. Suddenly Aladin appears and offers the Sultan the riches of the grotto if he will grant Laila to him in marriage. Mulak is astonished by Aladin’s reappearance; he had thought him dead, left behind in the grotto. He counters Aladin’s claim that Mulak only wants Laila so that he can claim the throne, by claiming that Aladin is in the service of an evil spirit. Infuriated, Aladin releases the lamp from his grip, in order to prove that he can win Laila’s hand without the aid of magic. It falls into Mulak’s hand and so the genie has to obey him. Mulak claims the throne, the treasure and the hand of Laila. Aladin is despondent, but the genie says that if his and Laila’s love is pure, the lamp will be filled with divine magic, and all will be well.

Act 3 Scene 5

Mulak is now in a gloomy mood. He cannot make the lamp shine again because – although he is fearless and believes in magic and miracles – his feelings are not pure. He attempts to gain Laila’s affection, but she denies him as she is under Aladin’s protection. He hatches a plan, whereby Laila will make the lamp shine for him in exchange for freedom to marry Aladin. In order to do this, she has to dance whilst holding the lamp. As she does so, Aladin rushes to her and takes her in his arms before Mulak can move. The brightly shining lamp brings about Mulak’s death, and all ends well.