Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

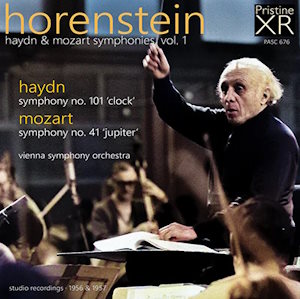

Symphony No. 101 in D, Hob 1:101, Clock (1794)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Symphony No. 41 in C, K551, Jupiter (1788)

Vienna Symphony Orchestra/Jascha Horenstein

rec. 1956, Brahmssaal, Vienna, Austria (Mozart), 1957, Studio C, Konzerthaus, Vienna, Austria (Haydn)

Pristine Classical PASC676 [56]

This is the first of three volumes which collect Jascha Horenstein’s (1898-1973) post-war recordings of Haydn and Mozart symphonies. In Haydn’s Clock Symphony, Horenstein’s taut exploration of the Adagio D minor introduction is striking, expecting danger, yet Haydn and Horenstein enjoy the art of the unexpected. The Presto D major main body is skipping. The second theme, with a droller hilarity, tumbles over repeated phrases yet takes over the movement in the development. The first theme has to be reconstructed from the strings’ unison skeleton. Horenstein reveals a dramatic undertow.

To compare, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham – recorded in 1958-1959 for Warner (5855132) – plays the movement some 20 seconds faster, and more deftly. Horenstein’s introduction has more character, and his tuttis in the main body are more exuberant, but I prefer Beecham’s more graceful second theme.

Horenstein conducts with beneficent regularity the Andante that gives the symphony its nickname. (The movement can be heard for free at the disc’s Pristine page.) Haydn’s genius gives us not just a clock but a couple dancing around it. Fun and devilment from Horenstein in giving full measure to the moment (track 2, 5:22) of five quaver beats’ rest when you fear the treat has vanished. There are individual stars around, like forwardly placed superb woodwind solos, as Misha Horenstein confirms in his excellent gatefold note. The dancers’ theme is marked p, but how quiet do you want it? Beecham’s is quieter and silkier, but the clock accompaniment seems rather heavy. I prefer Horenstein’s better balance of the two and greater presence of the dancers.

I find Horenstein’s Allegretto Minuet a mite too grand, as loud masculine tutti alternate with soft feminine passages. The tutti win: power obliterates charm. But charm returns in the Trio with flute solo and a conversation between flute and bassoon whose mischievous individuality outlasts the intervening power blasts. I prefer Beecham’s leaner, more scintillant strings in the Minuet, but I would choose Horenstein’s brighter, more dancing flute in the Trio over Beecham’s coyer one.

In the finale, Haydn maintains the charm with a soft first theme. Despite the loud tutti rejoinder, the feminine viewpoint had a fair hearing. And the grandeur is attractively energetic with violins’ running quavers. Where you would expect a second theme, there is a quietish development of the first (track 4, 1:28). The second development is a more characteristic one of the first theme in D minor. Horenstein treats it with great fiery sweep (2:42). The first theme’s next appearance is in D major in a stylish strings-alone fugato before the blazing tutti close. Horenstein secures riveting playing throughout.

Beecham, some twenty seconds faster, brings out the virtuoso quality of the tutti, especially the second development, but without Horenstein’s fire. You may, however, favour his strings’ more delicate, shadowy tracery in the fugato. In the earlier tutti, I favour Horenstein’s cleaner articulation of the violin’s running quavers.

Misha Horenstein’s note interestingly points out that his cousin’s Mozart was more controversial than his Haydn. But I find the first movement of Symphony No. 41 magnificently high-powered, a vigorous male first theme, the lady’s response and second theme not quite as matched in elegance, but the whole with supreme confidence in projection. Sadly there is no exposition repeat, sadly the norm in this account and in my comparison. That is the 1954 mono account by Otto Klemperer with the Philharmonia Orchestra (review). He takes 7:53, nineteen seconds more than Horenstein. I did not want a repeat from Klemperer. His approach is more abrasive, you could say stunning, where Horenstein is more energizing. Klemperer benefits from a recording of greater density.

The Andante cantabile slow movement is a dreamy state between sleep and waking. But how to treat the loud chord at the end of the first two soft phrases in a contrast of dynamics that recurs frequently? For me, a nudge rather than stab better suits the overall dreamy mood. Horenstein is more stabbing, but the recurrence of those two chords in violas and string bass is a little softer. Klemperer’s is not, though he is just as stabbing earlier. Best at not stabbing is Adam Fischer with the Danish National Chamber Orchestra in 2013 (Dacapo 6.220639). The loveliest, most memorable music is the seven-note motif at the end of the third theme, which Horenstein does fittingly and Klemperer a touch more winsomely. Nevertheless, Horenstein reveals with clarity and detail the drama which underpins this movement seeking gentleness.

The Allegretto Minuet is a conventional, polite strings’ dance but in the tutti the military context insists on making its presence felt. The Trio reinstates relaxation, the combatants appear again, but their efforts are defused. There remains the mindset of always being ready to think bigger. Klemperer, timing at 35 seconds less than Horenstein’s 4:37, headily precipitates forward, as if powerless to stop.

In the Molto allegro finale, the first theme – the opening four notes – is Mozart’s self-quotation from Missa brevis, K192 (1774), ‘Credo, Credo’ (I believe) as sung. The second theme (track 8, 0:11) is a continuation in the same mass: the first eight notes set to ‘In unum Deum’ (in one God). At this point in his symphonic journey, Mozart makes a spiritual statement. So does Horenstein. His account has a wonderful spirit of whirling impetus. You feel the players are giving their all, especially in the coda at 5:40, when five themes are combined. The result is a resplendent, determined sweep, an evangelical combination of gusto and cheerfulness. It is an advantage that neither exposition nor second half are repeated because the message is more spontaneous. Horenstein’s 6:29 looks much faster than Klemperer’s 8:20, but as Klemperer makes the exposition repeat, his equivalent time to Horenstein’s is 5:59. This is amazingly fiery and nifty but occasionally seems scrambled. Horenstein’s slower articulation is more humanely jocular.

Michael Greenhalgh

Availability: Pristine Classical