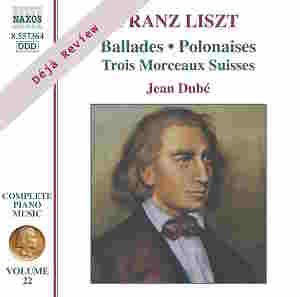

Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2005 and the recording is still available.

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Complete Piano Music Volume 22

Deux Polonaises, S223/R44 (1851) [20.55]

Ballade #1 in Db; “Le chant du croisé”, S170, R15 (1848) [7.37]

Ballade #2 in b, S171, R16 (1853) [14.21]

Au Bord d’une source, S156/2b, R8 (1836) [5.08]

Trois Morceaux Suisses, S156a (1836-77) [26.28]

Jean Dubé (piano)

rec. 2003, Potton Hall, UK

Naxos 8.557364 [74]

When I was twelve years old everybody knew who Franz Liszt was: he wrote the piano piece “Liebestraum,” the “Hungarian Rhapsody” and Les Préludes. Regarding the last, I remember wondering what that “S.P.3” in very fine print on the record album cover meant.

During his lifetime, Liszt was widely acknowledged, even by Eduard Hanslick, as the greatest pianist who had ever lived, but what Liszt wanted was to be remembered as a great composer. For most of his life and for a long time thereafter, his enemies were able to deny him this. Even before his death his compositions had virtually disappeared from the concert stage. He was considered to be a former pianist, now a teacher, but, beyond that, “merely” an arranger of existing music for his “use” as a virtuoso performer. However superficial, his piano music was considered by some to be morally corrupting and kept from the attention of piano students below the age of consent.

It wasn’t until the 1930s, fifty years after his death, that things began to change for Liszt, and not until the present day — over a hundred years after his death — that his surviving compositions were collected and edited into comprehensive scholarly editions. So not only is Liszt now properly honoured as a composer of great skill, the innovator behind Wagner’s boldest harmonic and textural explorations, the shape of this honouring emulates the honours accorded to another of Liszt’s idols, Bach (also a great arranger of other men’s music), in the gap of 100 years after his death before the publication of a comprehensive edition. The Searle catalogue lists nearly 800 works by Liszt in all genres.

To play the music of Liszt effectively a pianist must be the equal of the greatest pianist in the world ca 1850, must understand the personality of one of the musicians who created our very idea of Romantic music, must have in his or her personality a streak of adolescent showmanship which delights in astounding the audience, alternating with a profoundly pious spirituality and sense of the mysterious. His or her sense of good taste must be tempered by a deeply affecting sentimentality. Finding all these qualities in one person is almost impossible, but we are fortunate because many modern pianists can assemble all these characteristics on occasion, now and then, and if these moments coincide with time in a recording studio, the results are sublime. Over the years we can assemble performances of Liszt which fully reveal the master’s vision. But the chance of a single pianist attaining this parnassus of accomplishment more than one or two times in a lifetime is negligible. Horowitz achieved it twice, maybe even three times, Nyiregházi once, maybe twice. The odds against a single pianist playing all of Liszt’s music at this high level are virtually infinite. Even Liszt himself probably couldn’t do it.

Nevertheless, very good Liszt playing is more common now than it was fifty years ago. We are all aware of the great recorded series of the complete piano music of Liszt by pianist Leslie Howard, a series remarkable for consistent quality (so I am advised; I haven’t been able to hear more than a tiny fraction of it myself) and amazing in the scope of the works presented, and revelatory in the many works made available to listeners for the first time.

The 2002 Sixth International Liszt Piano competition in Utrecht awarded an unusual first prize: among other awards, the winner was to record the complete piano works of Liszt for Naxos records. The current disk is volume 22, the first in this series I have heard, and deals with some less well-known works. However, if this is scraping the bottom of the barrel, the barrel was once filled with 24 carat gold! Of the two Polonaises, Searle 223, it is the second in E which is the better known. György Cziffra’s recording for Philips is of a legendary performance, one of those recordings a great virtuoso achieves perhaps only once in a lifetime. Jean Dubé, an intense young man whose leaflet portrait shows him displaying what must be the largest and strongest hands of any human being on earth, does not equal Cziffra in this work, let alone surpass him. However Dubé’s performance of the less often heard first Polonaise in c “mélancolique” is brilliant, revelatory, and satisfying, if not quite the equal in either drama or subtlety of Peter Katin’s 1988 performance on Olympia. This work is less flamboyant, more symphonic in character, more reflective in mood as the subtitle suggests. This is first rank Liszt playing — not legendary, but first rank.

With the two Ballades, the temperature goes up somewhat, particularly with the second in b, S 171, where the competition is vicious. Dubé does not surpass either Horowitz or Nyiregyházi but is not terribly far away and may bring the music a little closer to us in feeling, if not in the brilliance of the fireworks. In the Horowitz recording, at some moments time appears to be totally suspended, at others one is afraid the piano will explode. Nyiregházi’s low register passage work was so menacing it scared my dog.

This Au bord d’une source S156/2b is the earlier version of the one eventually published as part of the collection Années de Pèlerinage. Liszt’s earlier versions are sometimes actually more complex than the later published version. After all, Liszt wanted to sell his published music and writing music nobody but him could play was not economically feasible, so he sometimes revised his works for publication making them easier to play and less complicated. Between Howard and Dubé we are privileged to be able to compare and evaluate this progression between early and late versions. Not having scores of both versions, I tried following this early version on the disk with the score of the later version and could see no obvious differences in the overall organisation of the work except in the final cadential chord which is more elaborated in this earlier version. Other differences may likely lie in detailed textures or fleeting harmonies.

It is in the final three pieces on this disk that the temperature approaches the lightning range. I have never heard these pieces before; they are not mere arrangements, but variations/fantasias composed by Liszt upon simple tunes by Huber and Knop. Many of Liszt’s finest works are in this fantasia-variations form, and these works, while they will never displace the Don Juan Fantasy in popularity, display the same skill. Whether we will ever hear them played any better is doubtful, and hardly necessary. I can see I need to hear some of the other disks in this series.

Paul Shoemaker

Help us financially by purchasing from