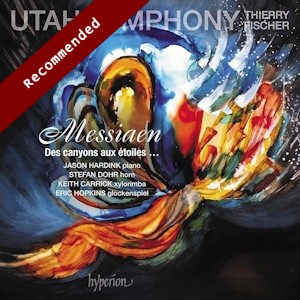

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992)

Des canyons aux étoiles . . . (1971-74)

Jason Hardink (piano); Stefan Dohr (horn); Keith Carrick (xylorimba); Eric Hopkins (glockenspiel)

Utah Symphony/Thierry Fischer

rec. 2022, . Abravanel Hall, Salt Lake City, USA

Hyperion CDA68316 [2 CDs: 92]

This major orchestral work of Messiaen with its unusual array of instruments has been recorded at least a half-dozen times, which attests to its important position among Messiaen’s oeuvre. I don’t think it has been performed all that much in concert, though I attended a performance in Washington, DC by the United States Air Force Band (including strings) under conductor David Robertson back in 2017, which included a video presentation of the Utah canyons and other images depicting ecological concerns. It was a momentous occasion, though I found the visuals a distraction from the music at times.

Messiaen composed Des canyons aux étoiles . . . (From the Canyons to the Stars . . .) as a commission from the American arts patron Alice Tully, who approached him in 1970 to write a piece for the American bicentennial. The composer was not as interested in American history as in the country as a place. When his wife, Yvonne Loriod and he visited the Utah canyons in the spring of 1972, Messiaen was astounded by the enormity of the colourful rock formations and by the many birds and their songs. This was the primary inspiration for the work, but he also used material from other sources. The famous horn solo, the Appel interstellaire (Interstellar Call), for example, was taken from a piece he composed in 1971 in memory of the young French composer Jean-Pierre Guézec. Of the work’s twelve movements, two are for piano solo—the fourth one, depicting Heuglin’s Robin, and the ninth, the Northern Mockingbird—and the one for solo horn. The others employ a large array of brass, winds, and percussion, with especially notable parts for xylorimba and glockenspiel, and a smaller contingent of strings. The fact that the title of the work concludes with an ellipsis is significant. While the music ends on a long major chord, this is not to be the actual conclusion of the piece. Rather, it is only a signal that the music will continue into infinity.

My first acquaintance with Des canyons aux étoiles . . . was with the CBS Masterworks recording performed by the London Sinfonietta under Esa-Pekka Salonen with pianist Paul Crossley, and hornist Michael Thompson. It seems that this is no longer available in the UK, according to Presto, but Amazon still lists it in the US. Salonen’s account retains its considerable attractions and also includes two other Messiaen works, Couleurs de la cite celeste and Oiseaux exotiques. Nonetheless, this new one by the Utah Symphony and Thierry Fischer surpasses it both in performance and sound as well as others I sampled. Preparation for Fischer’s recording included an actual performance by the musicians in one of the Utah canyons that inspired Messiaen, before taking the work into the studio for the recording. I would have loved to attend that! What makes this account so special, though, is the utter dedication that the forces project. Their enthusiasm is quite palpable. This is not the first Messiaen disc by Fischer I have heard. A number of years ago he recorded the Turangalîla-Symphonie with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, for whom he was principal conductor, which appeared as a BBC Music cover disc. It has remained my favourite version among other highly regarded commercial recordings in my collection. Fischer also chose this symphony for his farewell concert as music director of the Utah Symphony last year.

The Utah Symphony is a most natural orchestra to record Des canyons aux étoiles . . . , as the work appears to come home. I was not familiar with Jason Hardink before, but, besides being the orchestra’s principal keyboardist, he has performed as a pianist to acclaim in a number solo pieces, including Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus, and is considered a Messiaen specialist. Comparing his account with those of Paul Crossley (Salonen), Roger Muraro (Chung on DG), and Yvonne Loriod—for whom the part was written (Constant on Warner), Hardink’s is equal to any of them and clearly better than the less distinguished Tzimon Barto for Eschenbach (LPO). As far as the horn is concerned, only Michael Thompson (Salonen) equals the level of execution of the acclaimed Stefan Dohr, first principal horn of the Berlin Philharmonic. What makes Dohr outstanding, though, is the enormous exhibit of colour and variety of timbre he gets from his instrument, as well as the huge dynamic range. His timing for the Appel interstellaire is more than two minutes shorter than Thompson’s (5:03 vs. 7:31), but not so much in his tempos as in his less extended pauses. It is debatable which interpretation is better, and other recordings of the piece also vary this accordingly. In any case, as good as Thompson is, he seems relatively plain-spoken after Dohr, as does Salonen compared to Fischer.

The state-of-the-art sound on this new recording allows one to hear all the wonderful details of orchestration clearly and with real presence. The bird calls, whether from the piano, xylorimba, glockenspiel, piccolo, or even horn are evocative. One can also appreciate the geophone, a large drum filled with lead beads Messiaen invented for the work to depict the sound of the earth in the third movement. The low brass lacks for nothing in power and the shimmering strings conclude the work ecstatically. The two-disc set is further enhanced by Paul Griffiths’ informative, but succinct notes on the work. He describes each of the twelve movements individually, providing the reader all the detail necessary for the listener. Hyperion may have delivered only a single piece of music on this set, as there would have been room for others, but, given the quality of the performance and recording, one does not feel at all shortchanged. I, for one, would not want to listen to anything after this thrilling account of one of Messiaen’s masterpieces.

Leslie Wright

Help us financially by purchasing from

Previous reviews: John Quinn (June 2023) ~ Stephen Barber (June 2023)