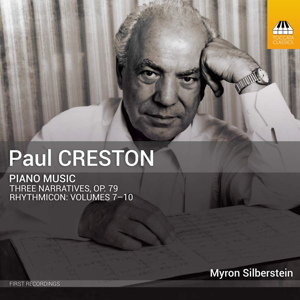

Paul Creston (1906-1985)

Piano Music

Myron Silberstein (piano)

rec. 2022, The Bronx, New York, USA

Toccata Classics TOCC0674 [69]

Interest in Creston enjoyed high standing in the USA during the 1940s and 1950s but tailed off after that. His music came to be associated with a growingly unfashionable romantic traditionalism. He was of the generation that included Menotti, Giannini and, with quite other geographical roots, Hanson. Its time would come again.

In his time he wrote six symphonies and concertos: two for violin and one each for piano, two pianos, marimba, accordion and saxophone. His first three symphonies were early debutantes in Naxos’ American Classics line. If you do not know it then start with the Second.

Adept pianist and advocate of music seemingly overtaken and buried by the constantly unfolding glamour of the new, Myron Silberstein has already won his place at the pilgrim’s Arthurian Round Table. There are his Naxos and Centaur CDs of Mennin and Persichetti. He turns now to Creston – another USA composer of Italian (Sicilian) blood line and born as Giuseppe Guttoveggio.

Creston’s Three Narratives from 1962, were written a few years after Howard Mitchell recorded Creston’s Second and Third Symphonies (Westminster LP) These pieces fume and flail. This exacting, superheated writing is a counterpart to the wildest Liszt (1), the fantastically glinting landscapes of Arnold Bax (2) and the grim depths plumbed by Griffes in his Sonata (3). The virtuosity is comparable with that of Raymond Lewenthal in his famed RCA Alkan/Liszt disc. In fact the Lewenthal sessions took place two or three years after Creston completed these works. The second Narrative is somewhat redolent of the story-telling essence that hangs over Medtner in his Skazki and Rachmaninov in his Etudes-Tableaux. Creston was, it seems, a titanic pianist and this shows.

Rhythmicon is a collection in ten volumes comprising 123 studies in total. Unlike the Narratives the ones heard here are quite short in duration, if tending toward being immense in spirit. Many are touchingly melodic, melting and romantically inclined: ‘Offertory’, ‘Interlude’ and ‘Salve Regina’ are examples. The 1970s zeitgeist, that held sway over academe and orchestral managements, venerated the thorny and dissonant. This militated against the success Creston merited.

The title of his ten books is fully justified time after time. Take the urgently possessed Mirror Etude as ‘evidence’. Quasi-Barbaro is as hard-bitten as anything and while it has its romantic asides always returns to a lash-driven, galvanising current. Other rhythmic highlights include Brief Encounter (no; nothing to do with the British film) which is darkly soused in vitality. The occasionally wacky titles for these brevities should not blind or deafen us to their emotional stamina. Creston’s ‘sjambok’ invention, his urgency, his sentimentality and his humour are all in plain ‘sight’. I doubt there is any link but the quicker and more furious pieces reminded me of a fairly different character from US music: Conlon Nancarrow and his hell-bent etudes for player-piano. Silberstein is equal to, indeed has a mastery over Creston’s demands, both technical and emotional and the recording likewise. This can, for example, be heard in his Nocturne; the one that concludes the penultimate volume. The final volume (10) has only four component pieces. I wondered if Creston had intended to add more.

Silberstein’s and Toccata’s immersion in these solo piano works should not blind us to the earlier six sets in Rhythmicon and to two of his works for piano and orchestra: the Piano Concerto and the Fantasy.

It comes as little surprise that these pieces are being heard in their “first recordings”. All credit to Toccata for this honest appellation. The industry should put behind it the fatigued and puffed up tautology of “world premiere”; what next: “galactic premiere”? Something is either commercially recorded first or it’s not.

Following their accustomed principles, Toccata supply very extensive liner-notes. They are by Walter Simmons. For America’s music of Creston’s generation, Simmons embodies the qualities of enthusiast, high priest and scholar. Enthusiast is not the least of these.

If you already have a taste for warrior celebrants of the piano such as Stevenson, Sorabji and Chisholm then line this one up in your sights. Let’s hope that Silverstein will next turn to the earlier books of Rhythmicon and perhaps some more orchestral works. Step forward Naxos and Albany.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Three Narratives, Op. 79 (1962)

Narrative No. 1

Narrative No. 2

Narrative No. 3

Rhythmicon: Volume 7 (1971)

No. 99 Affirmation

No. 100 A Jest

No. 101 Offertory

No. 102 Mirror Etude

No. 103 Interlude

No. 104 Salve Regina

No. 105 Child’s Play

No. 106 Quasi-Barbaro

Rhythmicon: Volume 8 (c. 1973)

No. 107 Hemiola

No. 108 Barcarolle

No. 109 Badinage

No. 110 Secret Game

No. 111 La Fontanella

No. 112 Pastorale

No. 113 Morning Song

No. 114 Brief Encounter

Rhythmicon: Volume 9 (c. 1974)

No. 115 Hommage à César Franck

No. 116 Jaunty James

No. 117 Brief Argument

No. 118 Psychedelic Waltz

No. 119 Nocturne

Rhythmicon: Volume 10 (1974)

No. 120 Toccata

No. 121 Meditation

No. 122 Burlesk

No. 123 Epitome