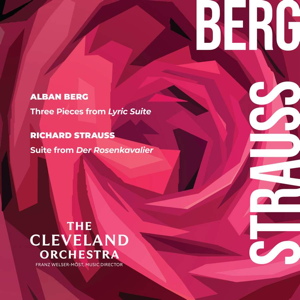

Alban Berg (1885-1935)

Three pieces from Lyric Suite

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Suite from Der Rosenkavalier Op59 (arr. Welser-Möst)

Cleveland Orchestra/Franz Welser-Möst

rec. 2022, Mandel Concert Hall, Severance Music Center, Cleveland, USA

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Album available as download only

The Cleveland Orchestra TCO0007 [56]

By the time Alban Berg came to write his Lyric Suite for string quartet in 1925, the baton of enfant terrible had most certainly been passed from Richard Strauss to Berg’s teacher, Arnold Schoenberg. If any work of Strauss’ signals the moment when Strauss recognised that his days at the cutting edge were over it would his opera of 1910, Der Rosenkavalier. With its retreat into a nostalgic past, Strauss is bidding farewell to the time when it was his music that was causing scandals across the musical world. Berg’s work by contrast might be seen as the single work that did most to promote the cause of the 12 tone or serial approach to writing music devised by Schoenberg. This latest download only release in the Cleveland Orchestra’s ongoing series of live recordings on their own label dramatises one of the most significant watershed moments in the history of classical music in the twentieth century.

Welser-Möst has had a hand in adapting this orchestral suite from Strauss’ opera basing it on the work of Robert Mandell. It is in three sections, each following the three acts of the opera. I think this is sensible as otherwise, in the absence of plot, this music can come to feel like being force fed Sachertorte. More controversially, the Austrian’s handling of the music is very limpid and delicate where one might want a bit more of Karajan’s swashbuckling vigour to offset the sweet treats. On the plus side, particularly in the absence of voices, what you get is to hear the range of Strauss’ orchestration in the most precise detail imaginable. Certainly in a manner unthinkable in the theatre.

The middle act, as in the opera itself, brings more vitality but even here Welser-Möst is a cool customer seemingly determined to avoid any more sentimentality than is strictly necessary. I confess I struggled a bit with this even as I revelled in the manifold delights uncovered. Shouldn’t Der Rosenkavalier, more than any other opera I know, be sentimental? Isn’t that an essential part of its DNA? As a result, I was left thinking of this as an interesting alternative experiment rather than being wholly convinced. Worse, I suspect if I got this in the opera house I would emerge feeling impressed but a little shortchanged. Typically, the big waltz tunes are playing ravishingly but without sufficient schwung. There is something to be said for stripping away the accretions but equally there is risk of a baby bath water situation.

More seriously I really wanted more rapture at the end of Act 3. This is music meant to bring a lump to the throat and frankly it didn’t. To leaven this negativity, I did come away with a much higher opinion of the work than I did when I started. Strauss may no longer have been ringleader of the iconoclasts but there was still no one like him when it came to dreaming up extraordinary sounds from the orchestra.

We now know following the 1977 discovery of a copy of the score of the Lyric Suite, that the music records in elaborately coded form a passionate extra marital affair undertaken by the composer with Hanna Fuchs-Robettin. Not that anyone needs that information to be able to tell that this is music of towering passion. Twelve tone music because of the difficulties involved in explaining its processes in layman’s language is often unfairly seen as arid exercises in intellectualism. Perversely, Berg’s music is still mistakenly daubed “wrong note romanticism”. The relatively cool precision of this new account takes Berg much closer to his partner in crime and fellow Schoenberg alumnus, Webern. The passion on display here is very different from that of Richard Strauss or Zemlinsky to whom the work was dedicated. There are other ways of doing this music – others, for example Karajan, emphasis the links backwards, stressing the connections to high romanticism.

The watershed moment I mentioned at the start of this review is startling obvious in contrasting the two works – they breathe very different air. Berg’s melodies – yes, there are melodies – ache and throb under the fingers and bows of the wonderful Clevelanders but in a way that is wholly convinced and convincing rather as some kind of substandard Wagner. The strange beauty of Berg’s writing emerges from its influences. There is an odd kind of paradox raised by this recording in that performances which tend to emphasise the romantic side of the work succeed in making the work harder to grasp by the novice listener. Welser-Möst’s cooler, more modernist approach seems to make it lovelier and easier to approach. Perhaps it is a case of confidence in the music meaning none of the performers are trying too hard.

What we get here are the composer’s own arrangement of the middle three movements of the string quartet original for string orchestra. Normally, the price to pay for this arrangement is a loss of intimacy but Welser-Möst draws playing from a full bed of strings that is almost chamber like in its delicate interplay. It really is a case of the best of both worlds.

There is no denying that these two works – in their very different ways arch Viennese – make odd bedfellows even though in putting them together they vividly dramatise the great divide that opened up in music at this time. As with most of the series of recordings to which they belong, they seem to be more about showing off different aspects of the stupendously talented Cleveland Orchestra than any real programmatic approach – and why shouldn’t an orchestra this good indulge in a little showing off? The bigger issue perhaps is that a lot of listeners will want their Rosenkavalier bitte mit mehr sahne than that which Welser-Möst serves up. The Berg on the other hand is astonishing and cries out for a full exploration of the Second Viennese School by these marvellous musicians.

David McDade

Help us financially by purchasing from