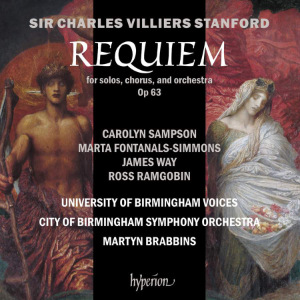

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

Requiem, Op 63 (1896)

Carolyn Sampson (soprano), Marta Fontanals-Simmons (mezzo-soprano), James Way (tenor), Ross Ramgobin (baritone)

University of Birmingham Voices

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Martyn Brabbins

rec. live, July 2022, Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Texts & English translation included

Hyperion CDA68418 [74]

This recording was made at a live performance on 2 July 2022 (with, I believe, a bit of patching the following day). Though I have owned the previous recording of Stanford’s Requiem for many years, I have never had the opportunity to hear it live. I hoped, therefore, to attend the concert and review it for Seen and Heard but a diary clash thwarted that hope. My disappointment was reduced when I learned that the performance had been recorded, and now here it is.

The Requiem was premiered at Birmingham Town Hall (as part of the Triennial Festival) on 6 October 1897, so the performance in 2022 celebrated, slightly in advance, the 125th anniversary of the premiere. At the start of his booklet notes David Kettle poses the question why Stanford, a staunch Irish Protestant, should compose a setting of the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead. He tells us that Stanford designed the work as a tribute to his close friend, the music-loving painter, Lord Frederic Leighton who died in January 1896; Leighton was a Catholic. In fact, the Requiem was not the first occasion on which Stanford had set the text of the Mass: he composed a Mass in G, Op 46 in 1891/92 and this, written to a commission, was specifically designed for liturgical use (review). Towards the end of his career Stanford returned to the words of the Mass in his Mass Via Victrix, Op 173, composed between 1914 and 1918 (review). Furthermore, in his biography of the composer, Jeremy Dibble refers to no less than three a cappella Mass settings which Stanford composed in the last few years of his life, one of which was performed by the choir of Westminster Cathedral; it seems that all three are now lost.

There has been one previous recording of the Requiem. In 1994 Adrian Leaper conducted Irish forces in a recording that was issued by Marco Polo (8.223580-1). I bought those discs and the recording is still available, having reappeared on Naxos. The Leaper recording has served well but, comparing it with the Brabbins version, I think the newcomer definitely has the edge. Amongst other virtues, the Hyperion recording has more space around the choir, who are also, I think, a better ensemble than their Irish peers, Crucially, the soloists are recorded with much more presence and impact; the Marco Polo/Naxos team are placed more distantly and, at least as recorded, sound somewhat bland. It’s also worthy of note that Adrian Leaper’s reading takes 80:43 against Martyn Brabbins’ timing of 74:26. Stanford’s score often invites spaciousness but I think Brabbins’ sometimes more urgent approach pays dividends. I’d already decided my preference lay with the Hyperion recording when I looked at MusicWeb to see if we had carried any reviews of the Leaper; I came upon this appraisal by Em Marshall-Luck. I agree with her assessments of both the recording and of the work itself.

In the Hyperion booklet, David Kettle describes Stanford’s Requiem thus: “It is a deeply personal, tender and intimate setting of the Catholic Mass text, as befits a work written in memory of a friend, and also one that focuses – like Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem, which Stanford had brought to Cambridge two decades earlier – on themes of consolation and renewal, never on the terrors of judgement and damnation”. Though the Brahms comparison is apt, another appropriate parallel might be with the Requiem of Dvořák, premiered at the Birmingham Festival of 1891. Although it contains a few dramatic passages, Stanford’s response to the Requiem text is nowhere near as red-blooded as was Verdi’s. That said, it appears that Verdi admired Stanford’s Requiem. In his comprehensive biography of the composer, Charles Villiers Stanford. Man and Musician (2002) Jeremy Dibble records that Stanford sent the score to his Italian colleague in 1898 and received the following reply: “Very flattered to have received your Requiem. It has made an excellent impression on me. It is very well written: written like a master, as a rule I would have expected it from a composition signed Stanford”.

The Introit provides a fine opening to the work. Beginning with simple, quiet music, Stanford proceeds to a radiant climax for chorus and orchestra at ‘Et lux perpetua’. These opening pages are amongst the most memorable in the work. The soloists feature in the Kyrie but are even more prominent in the Gradual (‘Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine’), which is scored for the quartet and orchestra. This movement features lovely, light textures in the orchestration.

The ‘Dies irae’ is not a Verdian raging storm; rather, it opens somewhat apprehensively. At the ‘Tuba mirum’ Stanford’s writing is overtly dramatic, complete with brass fanfares. Another dramatic passage comes later, at the ‘Confutatis’ but here the strong writing for chorus and orchestra is tempered by gentler passages involving the soloists. There’s also a weighty climax to the ‘Lacrimosa’. Elsewhere in the Sequence, however, the tone of the music leans much more towards lyricism. One such example is the ‘Quaerens me’ in which the baritone soloist and chorus sing. I mean no disrespect to the singers – Ross Ramgobin does very well – when I say that my ear was caught particularly by the attractive woodwind writing. The concluding ‘Pie Jesu Domine’ is especially successful; it’s a lovely, tranquil ending to the Sequence.

The Offertorium (‘Domine Jesu Christe’) opens with music that has the character of a confident but in no way aggressive march. Later, perhaps inevitably, Stanford sets the words ‘Quam olim Abrahae promisiti’ as a choral fugue; this may be a conventional device but Stanford’s fugue is a good one and the University of Birmingham Voices sing it in a spirited fashion. I like the ‘Hostias’ section, which is for the solo quartet with orchestra. The music is easeful and charming, though later on it builds up something of a head of steam. No less attractive is the Sanctus which features gently luminous writing for choir and orchestra. Here, I think Stanford’s lovely music is nothing less than inspired. The setting of ‘Pleni sunt caeli’ is majestic, after which Stanford reverts to the style in which he began the movement. In the Benedictus Stanford follows convention by setting the text for the solo quartet. This is a relaxed section in which the music is light, fluent and charming.

To bring the Requiem to an end Stanford writes a movement in which he combines the Agnus Dei followed immediately by ‘Lux aeterna’. The Agnus Dei is a dignified prayer with something of the character of a subdued funeral march. The ‘Lux aeterna’ is introduced by a lyrical supplication from the solo tenor. The section achieves a powerful climax before we hear more of the funeral march from the orchestra. The last word is given to the chorus who, supported by the orchestra, bring the Requiem to a luminous conclusion.

There is, then, a great deal to admire and enjoy in Stanford’s music. The same is true of the performance. The solo quartet do a fine job. I especially liked the gleaming soprano of Carolyn Sampson and the warm, round sound of Marta Fontanals-Simmons. James Way’s tenor seems a little underpowered but he sings clearly and pleasingly. Ross Ramgobin provides a good foundation to the quartet. All four soloists are to be preferred to their counterparts on the Leaper recording.

The choir has a lot to do in Stanford’s Requiem. Though contrapuntal writing is by no means eschewed, a good deal of the choral writing is homophonic – and none the worse for that. As I listened to the performance it struck me that the chorus writing must be very rewarding to sing; there’s plenty of satisfyingly broad music into which the singers can get their teeth. The contribution of the University of Birmingham Voices is very accomplished and it’s no surprise to learn from the booklet that their choirmasters are Simon Halsey and Julian Wilkins, who also preside over the better-known CBSO Chorus. There seems to be a strong input into this project from the University of Birmingham; not only does their choir take part but the recording was supported financially by the University’s recently retired Vice Chancellor. How fitting, therefore, that I believe two of the soloists – Carolyn Sampson and Marta Fontanals-Simmons – are alumni of the University.

The CBSO plays splendidly throughout. The collective response is sonorous and there’s an abundance of expert solo work to enjoy and admire The performance could not be in better hands than those of Martyn Brabbins. His conducting demonstrates evident empathy with the score and it seems clear that he brings out the best in all the performers.

Phil Rowlands led the engineering team for this recording and the sound is first rate. The climaxes open up warmly and the listener gets a good sense of the perspectives in the hall.

Stanford’s Requiem is a noble work and it’s an important score among his compositions. Like much of the rest of his output, it fell into neglect after his death but, as this fine performance demonstrates, that neglect was wholly unjustified. 2024 will mark the centenary of his death and whilst I’m not holding my breath for many concert performances of works such as his symphonies, fine though they are, I hope we may find some new recordings of his music will be issued. This recording of the Requiem offers us something to whet our appetite for the centenary year. It was in Birmingham that the work was first performed; 125 years later, the city did Stanford’s memory proud.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from