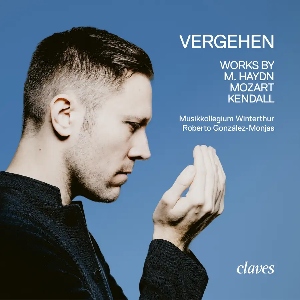

Vergehen

Michael Haydn (1737-1806)

Symphony No. 28 in C (1784)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Symphony No. 41 in C “Jupiter” (1788)

Hannah Kendall (b. 1984)

He stretches out the north over the void and hangs the earth on nothing (2024)

Musikkollegium Winterthur/Roberto González-Monjas

rec. 2024, Stadthaus, Winterthur, Switzerland

Claves 50-3113 [69]

The Swiss town of Winterthur, a little more than ten miles from Zürich has a rich musical legacy. The Musikkollegium can trace its history back to 1629. For a glorious period in the 1920s and 30s the great Hermann Scherchen put it on the map for contemporary music and some starry names could often be seen in the town. Recently, the orchestra has been led by the likes of Thomas Zehetmair, Douglas Boyd, Jac van Steen and Heinrich Schiff. They give many symphony concerts each season and in addition play at the Opernhaus, Zürich.

Ex-leader of the orchestra Roberto González-Monjas has been in charge since September 2021. He has also recently taken on the role of principal conductor of the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg. This CD is the last of a trio of records he has made with his Swiss orchestra for Claves, based on the three majestic last symphonies of Mozart, written in June, July and August of 1788. In each disc he has presented a symphony accompanied by a bedfellow from another hand. Symphony No. 39 came with Beethoven’s Consecration of the House, Symphony 40 with Haydn’s 49th and J.C. Bach’s Op. 6/6 (very clever). The discs also include a contemporary piece of music by a female composer.

The records have been called “Become”, “Being” and “Transcending” in translation. In fact, I understand this theme has been an over-arching one that has bridged the past three seasons for the orchestra. In 2024/25 the transcendental theme involved performances of Mozart’s Requiem, Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique.

With Mozart’s Jupiter symphony forming the basis for this record we begin with Michael Haydn’s C major symphony of 1788. This is number 28 in the conventional numbering system we normally use for his works. Michael, younger brother of Joseph spent his whole career in Salzburg working for the powerful Fürsterzbischöfe, namely in Michael’s case Schrattenbach (1763-71) and Colloredo (thereafter). His sacred music is beautiful, and Mozart evidently loved his orchestral work too. Michael had a close and respectful relationship with both Wolfgang and his father Leopold, and we believe that Mozart was heavily influenced by Michael’s symphonies in this period, particularly 23, 28 and 39. When he turned to his last symphony in that Summer of 1788, we know he consulted these works of Michael Haydn, all of which have fugato passages in the finale.

Symphony 28 employs trumpets and timpani as does Mozart 41. It is constructed in three movements and has a total duration of just a tad over twenty minutes. The first movement is charming with two contrasting themes nicely shaped here (suave bassoons in the second theme). I couldn’t get my hands on a score, but the structure of the work is quite easy to follow without one. The second movement is a stately gentle rondo. González-Monjas draws some lovely phrasing from his players here. Strings are light and play with minimal vibrato. The oboes, bassoons and horns are all superb. There is a contrasting central section which is more energetic and comes over here with great effect. There is a twinkle in the Musikkollegium’s rendition of this movement which is quite special.

The finale which so obviously inspired Mozart is wonderful. Haydn is at his contrapuntal fugal work within twenty seconds of the work opening and it is masterful. Over the six minutes of this finale, Haydn displays his skill not just of counterpoint, but in melody, harmony and sheer exuberance too. The players relish their parts and the performance is joyous. Listening to the coda is a revelation. Mozart was clearly not interested in this work purely for the fugato. So far, so good.

At 38 minutes this version of Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 is par for the course when we compare recent recordings from today’s bright young things on the podium. In fact, let’s do just that:

| Year released | Conductor | Orchestra | Label | Overall timing |

| 2025 | González-Monjas | Musikkollegium Winterthur | Claves | 38:00 |

| 2023 | Emelyanychev | Il Pomo d’Oro | Aparté | 38:31 |

| 2022 | Klumpp (review) | Folkwang Kammerorchester Essen | Genuin | 36:47 |

| 2021 | Chauvin | Le Concert de la Loge | Alpha | 35:08 |

| 2021 | Manacorda | Kammerakademie Potsdam | Sony | 37:09 |

| 2020 | Minasi (review) | Ensemble Resonanz | Harmonia Mundi | 39:38 |

Incidentally Herbert Blomstedt, the oldest conductor to give us his reading of the sublime work on record brings it in at a comparable 38:27 (review).

The performance by the Musikkollegium is characterised for me by its attention to the little things. The balance between wind band and strings is admirably considered throughout. There is some lovely phrasing and ornamentation much in evidence as motif cells end or blend into others. Roberto González-Monjas is dynamic, surprising us with a hard accent here and a gentle drawing out of a phrase there. It is all done within the natural pulse and drive of the music however and nothing seems vulgar of done purely for effect. One may subjectively disagree with a decision here and there (I did a couple of times) but artistic licence is to be encouraged, especially in Mozart if the musical message is paramount; and it is here.

The least successful aspect of his reading is the andante cantabile. It is just a shade too fast and the singing quality it wants is rather lacking. Ensemble is so tight though and the musicianship of these artists is impressive. Once more, one marvels at the lovely balance they achieve as themes are passed between sections, and groups take turns in the singing and accompanying, so carefully crafted by Mozart.

After a warm minuet, the finale arrives. I like the pulse of this movement very much. I am less enamoured by some points of emphasis González-Monjas underlines. The rests at bar 35 are prolonged excessively and the retardation continues to an exaggerated elongation of the ensuing semibreves in the seconds. The tempi soon recovers but it is an unnecessary device. Later (in the development), there is another regrettable moment where he has his violins play in a bare almost sangfroid style. I wish he hadn’t. These little moments aside, it is an enjoyable ride.

The magnificent fugal coda of this work is in truth, the inevitable end-journey of so much harmonic theme development in the movement. I like a performance that gives me time to hear this and at 12:39 this one does. There are better versions of the work (a couple in the table above actually) but there is much to admire in this new one and I am glad I heard it. I wonder how working with the orchestra in Salzburg will shape the conductor’s view on the work.

The CD ends, as did the others in the series with a new work. Hannah Kendall herself writes in the notes about this one. The title is from Job and musical inspiration derives from Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 and Mozart’s Jupiter. The piece is only ten minutes long but packs quite a lot in. Some interesting writing for low woodwind and brass, English fantasia-sounding strings, a Mozartian music box and a pre-recorded vocal track vocalises on verses from Job. There are some other devices she uses too. I was unsure what it all meant but the piece is interesting and varied for sure and is a world premiere on disc.

So, an end then to an enterprising series of records, that have explored the great trio of symphonic works from 1788, framing them in this ingenious way. I wonder what project this combination of orchestra and conductor will turn to next.

Philip Harrison

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free