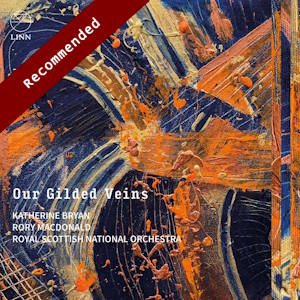

Our Gilded Veins

Jay Capperauld (b.1989)

Our Gilded Veins (2000)

Anna Clyne (b. 1980)

Within Her Arms (2009)

James MacMillan (b. 1959)

For Zoe (2022)

James MacMillan

The Death of Oscar (2012)

Martin Suckling (b. 1981)

Meditation (after Donne) (2018)

Peter Maxwell Davies (1934-2016)

Farewell to Stromness (1980)

Katharine Bryan (flute)

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Rory Macdonald

rec. 2024, Scotland’s Studio, Glasgow

Linn CKD713 [72]

This collection was recorded in the Royal Scottish National Orchestra’s own studio in Glasgow. The sound is superb. That the performances are also superb, and above all that they are deeply committed to realising the vast possibilities of each work, will be evident to anyone with ears to hear. Four of the works were composed within the last 15 years, and much of the programme will be unfamiliar to many listeners. Paul Conway, in an excellent booklet note, makes a brave stab at teasing out common threads, but the fact is that there is huge diversity here of aims and of manner. Few, I think, will want to listen to the programme from beginning to end, but it has been carefully constructed to allow this if the listener so wishes.

The four-note motif that turns in on itself to open Anna Clyne’s Within Her Arms would seem decidedly slim material indeed from which to create a piece of music. Yet in its 13 minutes this work, for 15 solo strings, dedicated to the composer’s mother, who died in 2008, is a powerful meditation on loss. The most striking passage occurs about half way through, where growling basses support fragments of theme that are well described by Conway as ‘static’ and ‘numbed’. From that point onwards, however, the music seems to be attempting to move on, to evolve from a state of mourning to something more like healing. A sudden and lengthy silence leaves us wondering, and thereafter rich and passionate textures lead us to the close, where the music dissolves into silence, bringing some comfort. This is tonal music that can be appreciated on a first hearing, but like the finest art, it gives a little more each time you come back to it. It put me in mind of another elegiac piece for strings, The Day Dawn by Sally Beamish.

For Zoe is a tribute to Zoe Kitson, who was for eight years this orchestra’s principal cor anglais player. It is dignified and sincere; we would expect no less from James MacMillan. The cor anglais plays throughout, accompanied by strings and harp. A central section, where a solo string quartet delivers some busy yet restrained counterpoint under held notes from the soloist, brings a little contrast. Otherwise, the cor anglais sings its dignified song, and disappears into the distance in a series of gentle, fanfare-like farewells. Henry Clay delivers the solo line with the utmost skill and sensitivity.

MacMillan’s The Death of Oscar is completely different but equally just as compelling. Oscar, son of the legendary Scottish warrior, Ossian, is victorious in combat against his father’s enemy. The work can be heard as a narrative, full of dramatic and conflicting sequences. In the central section, which surely describes the battle itself, military brass fanfares with many syncopations are heard over a regular, heavily treading pulse. This leads to a fearsome and highly dissonant climax. Yet Oscar, in spite of his victory, later dies from his wounds, so there then follows a lament, given out by cor anglais over a sustained string accompaniment. This music is deeply affecting, yet MacMillan does not leave it there, for a dramatic crescendo leads us to a final passage in which he pulls no punches at all. This is a fine work from one of the finest of living composers.

Martin Suckling’s Meditation (after Donne) was composed for the centenary commemorations of the Armistice of 1918. The work is made up of three main musical elements. Church bells, recorded from churches throughout Scotland, chime throughout, ‘tolling bells created by live electronics’, as the composer describes them. Then there is a string passage that begins timidly, with bells and discreet percussion in the background, but which rises to a restrained climax. The third element is given out by two oboes, a biting, open-air effect. The work ends calmly with elements of birdsong added to the bells. This is a carefully constructed piece whose static feeling is appropriate to its title. It was inspired by the famous passage from John Donne that incites us not to wonder ‘for whom the bell tolls’.

Those listeners who remain wary of the music of Peter Maxwell Davies can be reassured about the work that closes the collection, Farewell to Stromness. This short piece is firmly in the major key, and its wistful, gentle sadness reflects what would have happened to the Orcadian town of Stromness had a proposed uranium mine nearby seen the light of day. The work, originally written for piano, has been arranged for a number of different forces; it is given here in a version for strings. Despite its short duration of – only four minutes – it is one of Davies’s best known works, and deservedly so: it weaves a gentle spell that tends to stay with you long after the music has departed.

Jay Capperauld is the youngest composer represented on this disc, and his work, Our Gilded Veins, the longest of the collection, is played first and gives the album its title. It will be useful to quote Paul Conway here. ‘The piece was inspired by the ancient Japanese are of Kintsugi … which involves repairing broken pottery by mending areas of breakage with a gilded lacquer in order to not only repair the object, but to highlight its previous damage. In this way, the break is celebrated as an essential part of the object’s history.’ Now I happen to like this notion very much, the last part in particular, when applied to objects that belong to me. Conway goes on to say that ‘As the work unfolds, there is a growing … sense of purpose as attempts are made to reconstruct the [thematic] material into a single, cohesive unit.’ This is as close as we will get, I think, to understanding the parallels between the musical work and the Japanese technique that inspired it. The work was composed for the RSNA’s principal flute player, Katharine Bryan, and here she gives what must surely be one of the performances of her life. The soloist plays almost without a break, and must be worn out by the end. To say that the solo part is taxing would be a splendid understatement, and much of the music is genuinely fast, relatively rare in much contemporary music. There is no feeling that this is a concerto: the solo instrument, rather, is a leading character in a drama that begins with a high-pitched screech and ends in calm, yet not completely resolved, introspection. The music is freely atonal and highly dissonant for much of the time, but tonality is also fleetingly present in many passages. There is no attempt at Japanese pastiche. What we have instead is music that possesses genuine forward drive and which is eventful enough to ensure that the listener’s attention never flags. There is even a rather Mahlerian passage beginning at about the 12-minute mark. This leads to a stunning main climax, followed by a long, near-silence, after which the soloist introduces an extended melody that leads us to the end of the piece. Is the exultant passage shortly before the close just a bit too much? Some might think so, but you would need a ‘heart of stone’ to want to criticise it. Best to surrender to the extreme beauty of the sonorities the composer conjures up from the instruments at his disposal. Jay Capperauld has produced, in this piece, music of real distinction. There is drama and there is beauty, and there is also something very special, a kind of rightness, a kind of truth.

William Hedley

Previous review: Hubert Culot (September 2024 Recording of the Month)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free